Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

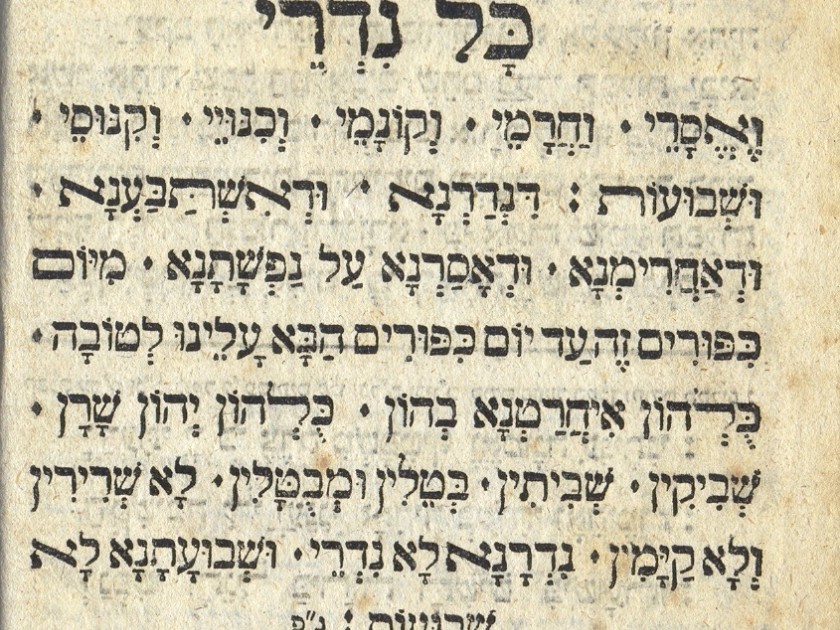

Kol Nidre, printed by Zvi Hirsch Spitz Segalderivative

Lori Gottlieb’s book Maybe You Should Talk to Someone is the author’s personal story of a therapist receiving therapy, and will have you laughing and crying along with Lori and her patients — as they each dive into their traumas and strive to understand themselves. As we approach Yom Kippur, we reflect on our actions and see how we can make amends and move forward. The following excerpt deals with self-forgiveness and repentance. Learn more about the book here.

— the opportunities they have; the financial or emotional stability that the parents provide; the fact that their children have their whole lives ahead of them, a stretch of time that’s now in the parents’ pasts. They strive to give their children all the things they themselves didn’t have, but they sometimes end up, without even realizing it, resenting the kids for their good fortune.

Rita envied her kids their siblings, their comfortable childhood home with the pool, their opportunities to go to museums and travel. She envied their young, energetic parents. And it was, in part, her unconscious envy — her fury at the unfairness of it all — that kept her from allowing them to have the happy childhood she didn’t, that kept her from saving them in the way she so badly wanted to be saved when she was young.

I’d brought up Rita in my consultation group. Despite her gloomy, Eeyore-like exterior, I told my colleagues, she was warm and interesting, and because I was free of the history her kids shared with her, I could enjoy Rita the way I’d enjoy a friend of a parent. I liked her quite a bit. But could her children really be expected to forgive her?

Did I forgive her? the group asked. I thought of my son and felt sick at the idea of anyone hitting him, of my ever allowing that to happen.

I wasn’t sure.

Forgiveness is a tricky thing, in the way that apologies can be. Are you apologizing because it makes you feel better or because it will make the other person feel better? Are you sorry for what you’ve done or are you simply trying to placate the other person who believes you should be sorry for the thing you feel completely justified in having done? Who is the apology for?

There’s a term we use in therapy: forced forgiveness. Sometimes people feel that in order to get past a trauma, they need to forgive whoever caused the damage — the parent who sexually assaulted them, the burglar who robbed their house, the gang member who killed their son. They’re told by well-meaning people that until they can forgive, they’ll hold on to the anger. Granted, for some, forgiveness can serve as a powerful release — you forgive the person who wronged you, without condoning his actions, and it allows you to move on. But too often people feel pressured to forgive and then end up believing that something’s wrong with them if they can’t quite get there — that they aren’t enlightened enough or strong enough or compassionate enough.

So what I say is this: You can have compassion without forgiving. There are many ways to move on, and pretending to feel a certain way isn’t one of them.

I once had a client named Dave who had a problematic relationship with his father. His father was, by his account, a bully — demeaning, critical, and full of himself. He had alienated both of his sons from a young age and had a distant and contentious relationship with them as adults. When his father was dying, Dave was fifty years old, married with children of his own, and he struggled with what to say at his father’s funeral. What would ring true? And then he told me that as his father lay on his deathbed, he had reached out for his son’s hand and said, out of the blue, “I wish I’d treated you better. I was a prick.”

Dave was livid — did his father expect absolution now, at the eleventh hour? The time to make repairs, he felt, was long before you left this earth, not on the eve of your departure; you don’t automatically get the gift of closure or forgiveness from a deathbed confession.

He couldn’t help himself. “I don’t forgive you,” Dave told his dad. He hated himself for saying this, regretted it the second it came out. But after all the pain his father had put him through and all the work he’d done to create a good life for himself and his family, he’d be damned if he was going to soothe his father now with a sugary lie. He’d spent his childhood lying about how he felt. Still, Dave wondered, what kind of person says this to his dying father?

Dave had started to apologize, but his father interrupted him. “I understand,” he said. “If I were you, I wouldn’t forgive me either.”

And then the strangest thing happened, Dave told me. Sitting there holding his father’s hand, Dave felt something shift. He felt, for the first time in his life, genuine compassion. Not forgiveness, but compassion. Compassion for the sad dying man who must have had his own pain. And it was that compassion that allowed Dave to speak authentically at his father’s funeral.

It was compassion, too, that helped me help Rita. I didn’t have to forgive her for what she’d done with her children. As with Dave’s father, that was up to Rita to reckon with. We may want others’ forgiveness, but that comes from a place of self-gratification; we are asking forgiveness of others to avoid the harder work of forgiving ourselves.

I thought of something Wendell had said to me after I’d listed my own regrettable missteps that I took great pleasure in punishing myself for: “How long do you think the sentence for this crime should be? A year? Five? Ten?” Many of us torture ourselves over our mistakes for decades, even after we’ve genuinely attempted to make amends. How reasonable is that sentence?

It’s true that in Rita’s case, her children’s lives were significantly affected by their parents’ failures. She and her children would always feel the pain of their shared pasts, but shouldn’t there be some redemption? Did Rita deserve to be persecuted day after day, year after year? I wanted to be realistic about the considerable scars they all bore, but I didn’t want to be Rita’s warden.

I can’t help but think about her evolving relationship with the hellofamily girls next door; what if she had been able to offer her four children what she offers them?

I put the question to Rita: “What should your sentence be, as you approach seventy, for the crimes you committed in your twenties and thirties? They were significant crimes, yes. But you’ve felt remorse for decades, and you’ve tried to make repairs. Shouldn’t you have been released by now, or at least out on parole? What do you think is a fair sentence for your crimes?”

Rita considers this for a moment. “Life in prison,” she says.

“Well,” I say. “That’s what you got. But I’m not sure that a jury that included Myron or the hello-family would agree.”

“But the people I care most about, my kids — they’ll never forgive me.”

I nod. “We don’t know what they’re going to do. But it doesn’t help them in any way for you to be miserable. Your misery doesn’t change their situation. You can’t lessen their misery by carrying it for them inside you. It doesn’t work that way. There are ways for you to be a better mother to them at this point in all of your lives. Sentencing yourself to life in prison isn’t one of them.” I notice that I have Rita’s attention. “There’s only one person in this entire world who benefits from you not being able to enjoy anything good in your life.”

Rita’s forehead becomes a series of lines. “Who?”

“You,” I say.

I point out to her that pain can be protective; staying in a depressed place can be a form of avoidance. Safe inside her shell of pain, she doesn’t have to face anything, nor does she have to emerge into the world, where she might get hurt again. Her inner critic serves her: I don’t have to take any action because I’m worthless. And there’s another benefit to her misery: she may feel that she stays alive in her kids’ minds if they relish her suffering. At least somebody has her in mind, even in a negative way — and in this sense, she’s not completely forgotten.

She looks up from her tissue, as if considering the pain that she’s carried for decades in an entirely new way. For maybe the first time, Rita seems to see the crisis she has been in the midst of — the battle between what Erik Erikson called integrity and despair.

Which, I wonder, will she choose?

Lori Gottlieb is a psychotherapist and New York Times bestselling author who writes The Atlantic’s weekly “Dear Therapist” advice column. A contributing editor for The Atlantic, she also writes for The New York Times, and appears as a frequent expert on relationships, parenting, and hot-button mental health topics in media such as The Today Show, Good Morning America, CBS This Morning, CNN, and NPR. Her most recent book Maybe You Should Talk to Someone is in development for a television series at ABC.