Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

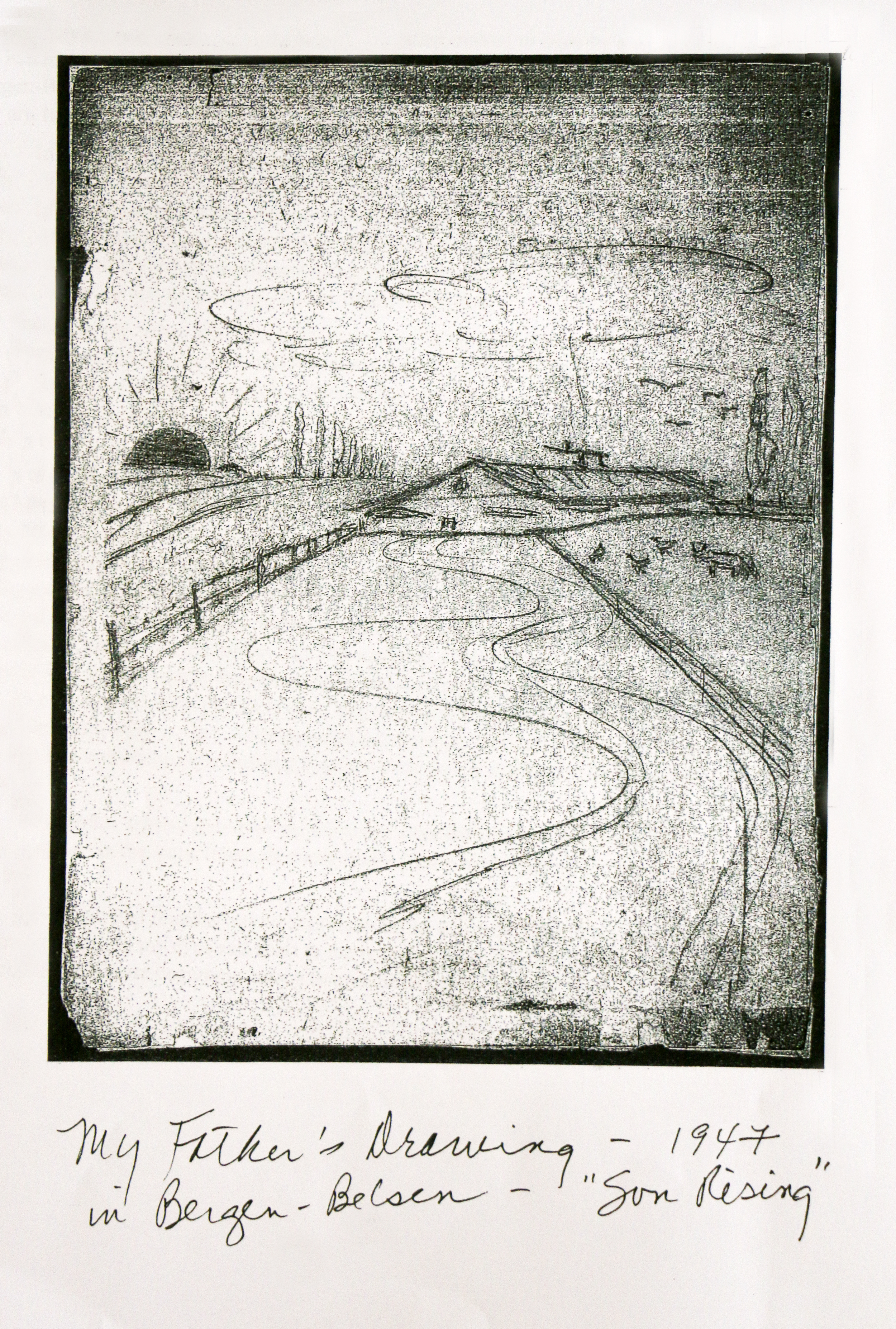

Ironically, my first awareness of actually being moved to tears by a work of art, was not in a museum nor an art book, but from a drawing my father had done, after the war, in Bergen-Belsen in 1946. My father’s drawing. My father had never spoken of ever having made any art. In reality, except for this one drawing, he hadn’t, not before nor after.

In 1949, among the few things my parents brought to America with them was an old black leather suitcase. I loved this old suitcase: the smell of it and the feel of it. I loved looking through the suitcase and seeing a few old photographs, as well as some Yiddish writings kept in a faded black leather journal. One day, alone in my room, looking through the suitcase, I found a Yiddish journal my father had kept after the war. Among the thin yellowed papers, a drawing fell to the floor. It was simply beautiful.

I ran to my father with this pencil drawing, breathless. The drawing, in fine pencil, was of a sun rising up over a barn. Outside the barn, animals and trees lined the walkway. The marks were abstract and simple. There was a strong sense of perspective, and the work seemed to hold a great deal of emotion. I was fascinated. I had never seen my father draw anything.

My father recollected that one clear, cool morning, after he and my mother were married and still living in the Bergen-Belsen DP camp, the view of the sun rising made his heart sing and the need to draw what he was witnessing was all consuming. When he told the story, I felt like crying. A sun! A picture of a sun rising in Bergen-Belsen. To capture the simple joy of the sun. My father was moved to make a mark. Remarkable. This drawing of the sun rising in such a bleak place expressed hope. Roland Barthes writes that love is found in a moment of recognition. In that very moment, alone with my father, and this drawing, I fell in love with the power of art. Art can make you feel. I believe this recognition was the first of many, confirming my desire to paint. To make art. I didn’t know it then, but now, looking back, I realize that seeing my father’s drawing was my first awareness that a drawing, a mark on a piece of paper, could make one feel something. The drawing expressed the power and ability of art to hold onto memory, experiences and emotion.

My mother framed this drawing in a beautiful cherry-wood box frame. This work, in the same frame, has hung in every house I have ever lived in, for the past sixty years.

My father had found a way to express what he was seeing and feeling after the war. This drawing opened my eyes and heart to the reality that art and life, intertwined, was meaningful. And there began my search to understand both.

Mindy Weisel, an internationally renowned artist, author and speaker, was elected into the Smithsonian Archives of American Artists in 2000. Her works are in the permanent collections of the National Museum of American Art, Oxford University and the Israel Museum, among many other public and private collections. Weisel is the author of Daughters of Absence: Transforming a Legacy of Loss and Touching Quiet: Reflections in Solitude. She is also a member of the United States Art in Embassies program. Weisel lived and worked, for over forty years, in Washington, D.C. and now resides in Jerusalem with her husband.