Earlier this week, Samantha Baskind wrote about the artist Jack Levine and about some of the artists she interviewed for Encyclopedia of Jewish American Artists. Her newest book, Jewish Artists and the Bible in Twentieth-Century America, is now available. She has been blogging here for the Visiting Scribe series all week.

Some of the most important twentieth-century American artists also happen to be Jewish. To this point they have been celebrated for their contributions to major art movements, like Pop Art, Abstract Expressionism, and Photorealism. As I was doing research on a number of these artists, mining their mainstream work for any Jewish content (implicit or explicit), I found that many addressed biblical themes. I made these discoveries by examining old exhibition catalogs, spotting an occasional reference in critics’ reviews of shows, a brief notation here or there in a book, or digging through an artist’s archived papers. I wondered: Why hasn’t anyone explored this distinctive theme in art by Jewish Americans? Why hasn’t anyone questioned why the subject has so far been ignored? Here’s a fascinating statistic that I knew deserved further inquiry: Religious imagery by twentieth-century Jewish American artists is so pervasive that of the initial American works purchased by the Vatican in 1973 for the new Gallery of Modern Religious Art, nearly half were by Jewish artists even though at that time Jews comprised just less than three percent of America’s population.

Some of the most important twentieth-century American artists also happen to be Jewish. To this point they have been celebrated for their contributions to major art movements, like Pop Art, Abstract Expressionism, and Photorealism. As I was doing research on a number of these artists, mining their mainstream work for any Jewish content (implicit or explicit), I found that many addressed biblical themes. I made these discoveries by examining old exhibition catalogs, spotting an occasional reference in critics’ reviews of shows, a brief notation here or there in a book, or digging through an artist’s archived papers. I wondered: Why hasn’t anyone explored this distinctive theme in art by Jewish Americans? Why hasn’t anyone questioned why the subject has so far been ignored? Here’s a fascinating statistic that I knew deserved further inquiry: Religious imagery by twentieth-century Jewish American artists is so pervasive that of the initial American works purchased by the Vatican in 1973 for the new Gallery of Modern Religious Art, nearly half were by Jewish artists even though at that time Jews comprised just less than three percent of America’s population.

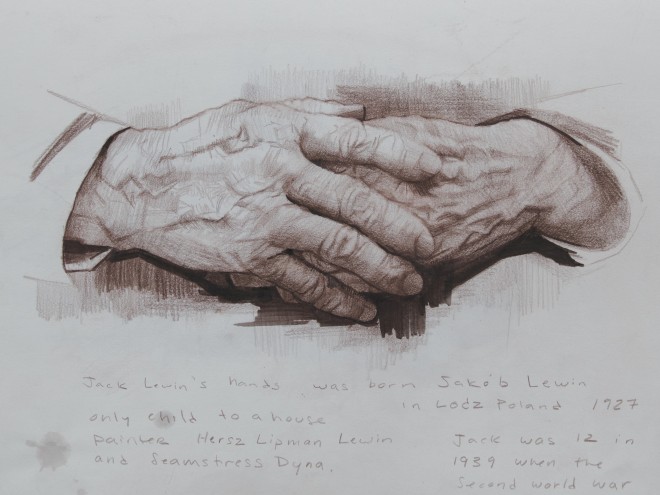

And so my research took me into museum archives, recesses of libraries leafing through dusty, decades old magazines, the homes of art collectors, and even to a few of the living artists’ homes. When sifting through old art, long since packed away – even from their teen years – the artists’ themselves discovered that biblical subjects occasionally interested them at a young age!

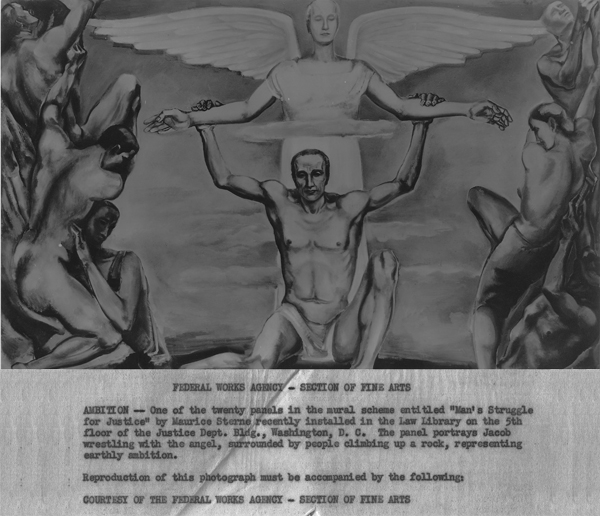

Some artists consistently depicted biblical subjects alongside their more common matter. Others only touched on the Bible. Sometimes the biblical reference was small and sometimes shockingly blatant, and this is in media across the board: paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, and book illustrations. Here’s one of the first instances I uncovered that made me think that a full-length study was in order: From 1935 – 40, Maurice Sterne – now a mostly forgotten artist who in his day was famous enough to command the first one-person exhibition by an American at the Museum of Modern Art (1933) – painted an immense twenty-panel mural, Man’s Struggle for Justice. Done under the auspices of the Federal Art Project, for the law library at the Department of Justice building in Washington, D.C., at times Sterne used allegory to make his points. The series comprises oil on board panels demarcating concepts of justice over the ages (e.g., Brute Force and Mercy), as well as the impact of modern life on justice (e.g., Red Tape and Scientific Evidence). Surprisingly, Sterne employed the story of Jacob wrestling with the angel for the panel Ambition, which merges the biblical past with present-day concerns. Sterne pictures the angel as seraphic, while Jacob appears mortal as do six additional muscular figures, three climbing a rock lining each side of the composition, “representing earthly ambition.” This interpretation, which I most likely would not have fleshed out on my own, was provided by the artist. Indeed, Sterne’s own interpretation appears on the back of a photograph taken soon after the panel installation, which I happened upon and luckily turned over while conducting research at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

This kind of stumbling on to material marked the origins of my book, which I originally thought might comprise an article. It was only when I realized that I would have hundreds of biblical works of art to deal with, by dozens of Jewish American artists, that I knew a full-length project was in order. I also realized that I had to get to the bottom of why these biblical works have been excised from the canon.

Thus was born Jewish Artists and the Bible in Twentieth-Century America.

Samantha Baskind is Professor of Art History at Cleveland State University. She is the author of several books on Jewish American art and culture, which address subjects ranging from fine art to film to comics and graphic novels. She served as editor for U.S. art for the 22-volume revised edition of the Encyclopedia Judaica.

Related Content:

- Reading List: Samantha Baskind

- Essays: An Artistic Eye

- Reading List: Jewish Artists

Samantha Baskind is Distinguished Professor of Art History at Cleveland State University. She is the author or editor of six books on Jewish American art and culture, which address subjects ranging from fine art to film to comics and graphic novels. She served as editor for U.S. art for the 22-volume revised edition of the Encyclopaedia Judaica and is currently series editor of Dimyonot: Jews and the Cultural Imagination, published by Penn State University Press.