Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

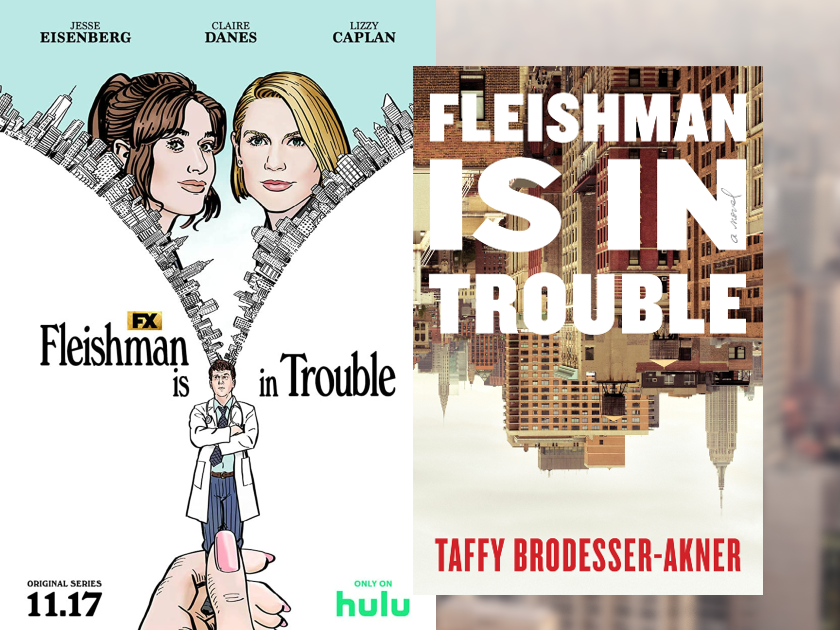

When the fall semester ended last December, I found myself in a position that many of us encounter when we happen upon a bit of free time: scrolling through the menus of various streaming services, looking for something to watch that would be both entertaining and worth my time. I settled on Hulu’s recent miniseries Fleishman Is In Trouble, an adaptation of Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s 2019 novel of the same name. The show stars Jesse Eisenberg as Toby Fleishman, a forty-something physician whose ex-wife, Rachel (Claire Danes), disappears the summer after their divorce is finalized.

In the end, Fleishman did not disappoint. Not only were the eight episodes both entertaining and worth my time, but they also offered a clever deconstruction of paradigms of femininity, masculinity, and familial dysfunction through a Jewish lens, all filtered through the narration of Libby (Lizzy Caplan), Toby’s best friend and the viewer’s major conduit through which to understand the nature of the Fleishmans’ break-up. Toby is neither as blameless nor as virtuous as he imagines himself to be. Rachel is neither the image-obsessed Jewish American Princess nor the shallow social climber that she initially appears to be. Libby, as the audience’s stand-in, is gradually forced to overcome her inherent biases against Rachel and, more importantly, against herself, rooted in her fears of conforming to any Jewish girl clichés.

The layers of the series unpeel themselves to reveal a seemingly simple but nevertheless crucial truth: that people are inherently complex, that they cannot be categorized by stereotypes or considered wholly good or evil. The fact that this truth appears against a backdrop of Judaism and Jewishness — both in the cultural markers of New York’s Upper East and Upper West sides and, in one particularly poignant scene, in a synagogue sanctuary where Toby performs the entirety of the Birkhat Kohanim in Hebrew for his daughter, a moody bat mitzvah-age teen questioning her identity in the midst of the Fleishmans’ familial chaos — challenges every truth perpetuated in American popular culture about unappealing and emasculated Jewish men, overbearing and demanding Jewish women, and disengaged secular Jews removed from and embarrassed by Jewish identity.

What Fleishman ultimately offers reflects the patterns that characterize the best of contemporary Jewish television, patterns that I explore in detail in my book, Peak TV’s Unapologetic Jewish Woman: Exploring Jewish Female Representation in Contemporary Television Comedy. While Jewish women historically have been offered the proverbial short end of the stick in television representation — tucked into one-dimensional Jewish American Princess/Jewish Mother roles; used as comic fodder on the basis of their neuroticism, unattractiveness, or brashness; or absent altogether — contemporary television offers a comparative embarrassment of riches. Changes in the industry have opened the door for Jewish women in television, both in front of and behind the camera. The proliferation of streaming series — on myriad platforms, available on demand to a diverse viewership that chooses when and what to watch outside the confines of traditional network schedules — combined with a growing desire to generate high-quality content with niche appeal have changed television. Jewish women have subsequently taken advantage of the onset of what can only be described as an era of Peak TV, and the Jewish female characters that have appeared on television in the past decade amount to a renaissance of Jewish female self-representation.

In my book, I use case studies of several series from the past decade created by, written by, and, in some cases, starring Jewish women and non-binary Jews in order to define the characteristics that make up television’s new, unapologetic Jewish woman. My exploration of series such as Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Broad City, Difficult People, Transparent, Grace and Frankie, Russian Doll, Orange is the New Black, and And Just Like That… ultimately demonstrate a truth that is not dissimilar to the truth Libby discovers towards the end of Fleishman Is In Trouble: that Jewish women are complex, not easily categorized, and, unsurprisingly, are most interesting when they are given space beyond the stereotypes that have confined Jewish female representation on television since its inception.

As my book reveals, the Jewish women featured in contemporary TV comedy share little in common with their historical counterparts, but they also share little in common with each other. The most significant change offered by the female-driven comedy series of the past decade is a diversification of television’s Jewish woman that eschews the idea of a singular model of Jewish female identity in favor of a varied spectrum of character traits, backgrounds, family dynamics, and relationships with Jewishness and Judaism.

The common threads that tie these post-network Jewish women to each other — a positively framed unruliness that emphasizes subjectivity and originality, an unapologetic connection to Jewishness/Judaism unobscured by coding or self-consciousness, outward-facing humor rooted in action rather than in self-deprecation, open sexuality, and a defiance of gender norms — ultimately come together to serve two important functions. First, they undermine historical representations of Jewish femininity, complicating and, in many cases, bypassing altogether the Jewish American Princess/Jewish Mother cul-de-sac of Jewish female representation in order to establish new tropes. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, they humanize the Jewish woman by individualizing her. This reconception of the Jewish woman as representing only herself allows for more complex, nuanced representation that leaves room for character flaws, comic mishaps, and precarious choices without communicating blanket messages about what all Jewish women are like.

These changes not only rehabilitate Jewish female representation, but they also deepen what Jewishness can mean on television and thus undermine classical popular culture tropes of Jewishness — hyper-assimilation, coded Jewishness, stereotypes, cultural whitewashing — in order to present a less self-conscious, more complicated, and “culturally narcissistic” version of Jewish identity that engages more meaningfully with Jewish culture in many forms.

Over the course of the series explored in Peak TV’s Unapologetic Jewish Woman, we see Jewish women (and Jews generally) lighting Shabbat candles, covering the mirrors for shiva, reciting the Viddui, fasting on Yom Kippur, putting together Passover seder plates, lighting yahrzeit candles, attending synagogue, participating in a Beit Din, exorcizing dybbuks, attending Yiddish poetry readings, visiting Israel, going to the Catskills, and, above all, claiming their Jewishness openly and without shame. The end result is an almost Talmudic exegesis of Jewish femininity and Jewish identity that diminishes the validity of classic archetypes, humanizes and empowers Jewish women, demystifies Jewish ritual, and, perhaps most strikingly, does so while avoiding all those pesky Jewish girl clichés. Peak TV, indeed.