Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

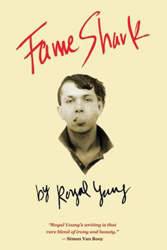

“I sound like a cheap, mean kyke,” my father raged. “I sound like an idiot, a complete non-entity,” my mother was furious too. I had been nervous about them reading my first memoir, Fame Shark, but none of my jitters had prepared me for this ballistic reaction. We were sitting down to breakfast at Castillo, a Dominican restaurant in New York’s Lower East Side where I had grown up eating delicious homefries colored orange from Sofrito. Now they stuck in my throat.

“I sound like a cheap, mean kyke,” my father raged. “I sound like an idiot, a complete non-entity,” my mother was furious too. I had been nervous about them reading my first memoir, Fame Shark, but none of my jitters had prepared me for this ballistic reaction. We were sitting down to breakfast at Castillo, a Dominican restaurant in New York’s Lower East Side where I had grown up eating delicious homefries colored orange from Sofrito. Now they stuck in my throat.

For me, the book was a monument to the obvious: I was in love with both my parents. But raised by two Jews who were brilliant psychoanalysts, my love had a darkness, a depth, an introspection I’d learned from them. Wasn’t that a good thing? Wasn’t that flattering?

“So, it’s basically fiction,” Mom said,“a lot of this stuff never happened.” It was true that I had purposefully pandered to a modern American culture that had the attention span of meth addicts. I’d cut all the “boring” bits out of my life in this telling. But fiction? No way. It had been hard, terrifying and humbling to write truths about myself: I had been bullied to the point of molestation as a kid, I had later exchanged sex for money and movie roles, cultivated friendships with drug dealers, sunk to supreme unhappiness at the altar of celebrity worship. I had begun writing Fame Shark still half in the throes of an idiotic, unoriginal fantasy that the book itself would lift me into celebrity. Only the therapeutic writing of it had helped take me out of my own narcissism/self-hatred (a diagnosis my parents had once agreed with, in our darkest conflicts).

It had been seven years since the last chapter of the book. Years I had spent doing hard work in real life. I had worked as a journalist at The Forward, Interview Magazine, New York Post and others. I had drastically cut back on drinking, stopped doing drugs, fallen in love with beautiful women, gotten my heart broken, fought hard through much rejection to see the publication of my debut memoir. But achievement was not redemption. Now, I feared my own creation was dragging me and my parents back to a black place of contention we had bravely worked past in family therapy sessions.

That first breakfast, my immediate reaction was to match their anger. Suddenly like a petulant teenager again, I swung between fury and sadness. I was outraged they didn’t “get” my art; I was crushed I didn’t have their seal of approval. Even more devastating, it seemed they felt the book was evidence of some deep malcontent I held toward them. The day ended with me crying on their couch.

Like any modern moron, I posted about my parent’s outrage on Facebook. “I thought they came across as very endearing. Feel free to pass that on :)” wrote one friend. “If your parents aren’t angry, then the memoir is no good. So congratulations!” typed another. It felt comforting to be supported by cyber solidarity.

But that didn’t seal up the hole in my heart. I had hurt Mom and Dad and was no longer the too skinny, shitfaced, stubborn and stylishly blasé adolescent who didn’t care a wit. I felt awful about it. Jewish guilt that got me angry all over again. Which I then felt awful about. It was a vicious Freudian cycle, a problem only a Jewish boy raised on the Lower East Side by two mental health professionals in the early ’90s could have.

There is another version of my life. My parent’s lives. My father is a handsome artist born in Detroit, who fled a conservative upbringing in the Midwest to pursue big city success. And he found it. He’s been commissioned to do several public art projects, many of which still adorn New York. My mother is a smart beauty who speaks seven languages and helps countless people rehabilitate their lives. They have always been inspiring, loving, creative parents who encouraged me to realize my own dreams. And even when uncomfortable with their portrayal in my writing, they have remained understanding, proud and unshakably loving towards me. The truth is people are complicated.

My way of digesting and dealing with life is through writing. My father’s through art. My mother’s through therapy. We all have different ways of exploring the powerful bonds of family. We all try to make sense of our closest relationships in the best way we can. We hurt each other, heal each other, learn from each other. The most important thing is that we do all this together, as a family.

There have been many and varied reactions to my book so far. The way I have tackled the main subjects of fame and family. But the response that never changes is that as a family “you were all so involved. You cared about what happened to each other.” And this aspect of my family is what enabled me to write so personally in the first place. Like it or not, my parent’s enduring love allowed me to explore our conflicts in a way I couldn’t have if we were fractured.

As my parents come to terms with my book, I hope to show them how my cautionary confession can help other people. A compassion I learned from them. There will always be struggle with the people we love the most, but it’s this love that remains our defining bond.

Besides, “You know I’m going to write about all of this too,” I recently told Mom and Dad. My parents both laughed. They had grown a sense of humor about having a scribe in the family. Though actually, I think my next book will indeed be pure fiction.