Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

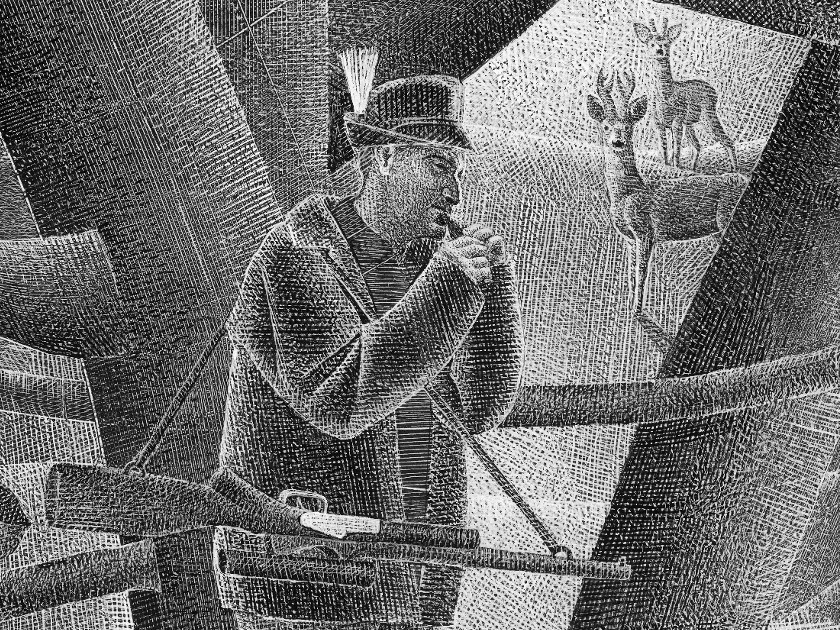

Cropped illustration by Alenka Sottler from The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest translated and introduced by Jack Zipes

For a century we’ve abided each other,

Giving our brotherly due.

You abide that I breathe,

And, though you rage, I abide you.

But occasionally, in dark times, good spirits in full flood,

Your tender, pious little paws have colored my blood.

Our friendship is firmer. It grows stronger as we age.

I’m becoming almost like you,

I, too, am beginning to rage.

—“An Edom,” Heinrich Heine (1824)

The story of Bambi was not written for children. It has become universally beloved through Disney’s films and books, which feature a heroic deer and cute animals who escape hunters and eventually celebrate Bambi’s marriage. In the original novel, however, there is no happy ending.

Bambi: A Life in the Forest was written by the Austrian Jewish writer Felix Salten in 1921. It is a parable of the way Jews and other minorities were treated as inferior and dangerous beings who deserved to be annihilated. Salten rejected his given name, Siegmund Salzmann, in an attempt to become more acceptable to Viennese society. Bambi, written soon after World War I, is a study of the loneliness of Jews and the precariousness of their lives throughout the world. Fascism was raising its ugly head.

In Salten’s version of Bambi, the fawn grows up in a forest where hunters kill deer and other animals for their pleasure. Most of Bambi’s relatives and friends are killed. To be a man in Austrian society, posited Salten, was to become a hunter — a murderer of helpless and hopeless victims.

Felix Salten was one of the most outspoken Austrian writers in the first half of the twentieth century. Although he sought to bring a message about the importance of civility to European and American readers, his works have been misunderstood, ignored, and exploited. It is important to explore why Salten failed, and why he turned to animal stories such as Bambi to express his conflicted feelings as a Jew who wanted to be accepted by elite Austrian society.

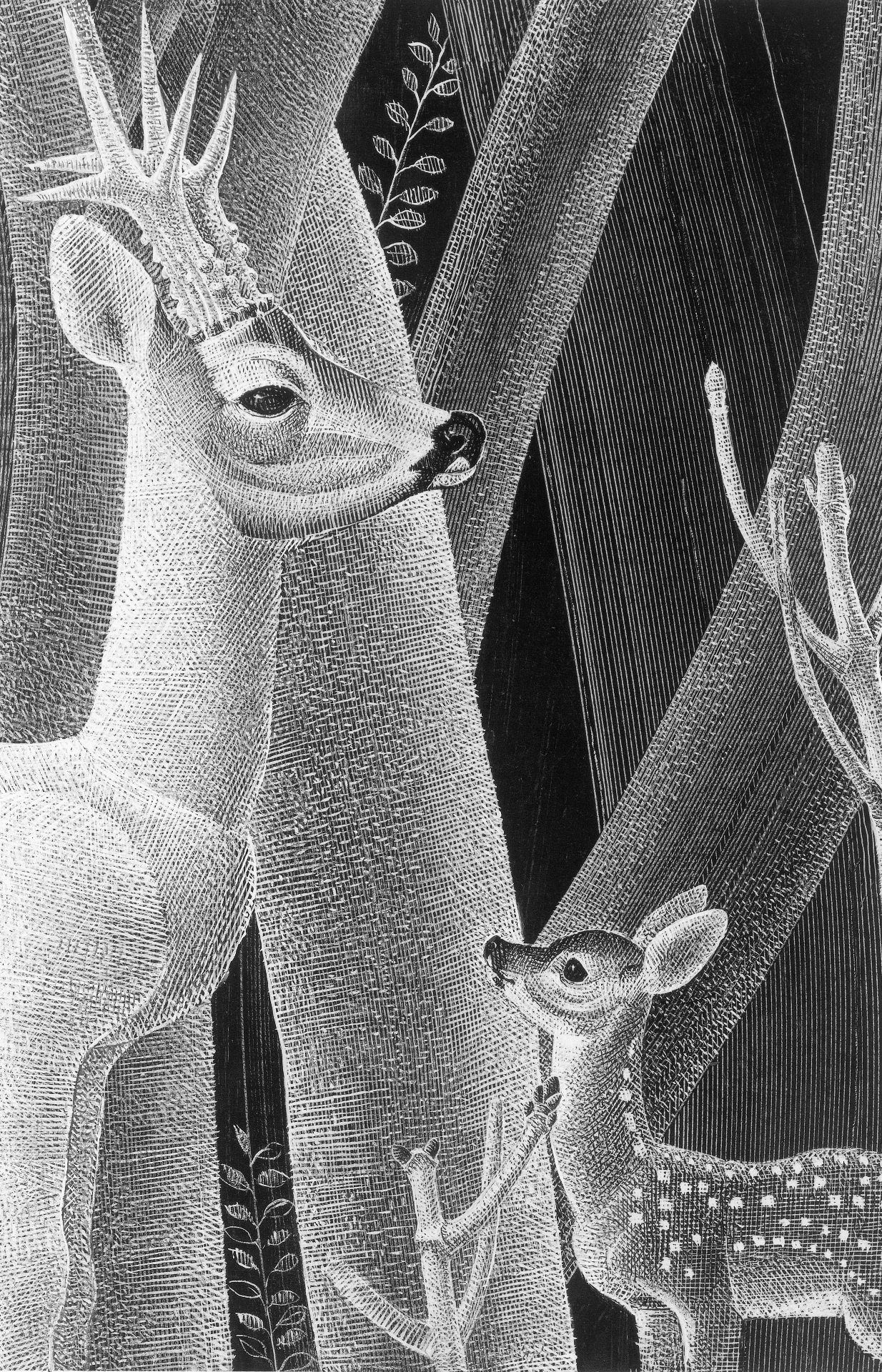

Illustration by Alenka Sottler from The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest translated and introduced by Jack Zipes

Siegmund Salzmann was born in 1869 in Pest, Hungary.His mother, Marie (née Singer), was a housewife, and his father, Philipp, was an engineer. Philipp appears to have acquired debts throughout most of his life, and when Siegmund was four years old, the family moved to Vienna to escape Philipp’s creditors. The Salzmanns considered themselves assimilated Jews. Yet, they were often beaten and taunted in the proletarian district of Vienna where they lived. When Siegmund turned sixteen, he left high school to help support the family. His first job was with an insurance company, and soon thereafter, he began working for various newspapers and magazines. Siegmund wrote under the name Felix Salten from 1889 onward; it was almost impossible to use a Jewish name if one wanted to succeed in Vienna.

In 1889, Salten began frequenting the Café Griensteidl, where the Young Vienna group of artists and writers (including Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Richard Beer-Hofmann, Hermann Bahr, Karl Kraus, and others) often gathered. At first, his background as a lower-middle class Jew hindered him from gaining recognition and acceptance by highly educated Jews. However, Salten was bright and opportunistic, often ingratiating himself to his “superiors,” and over the next decade, he learned a great deal from them. He soon became an editor at the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung and formed a friendship with Archduke Leopold Ferdinand — although their bond was tainted by the type of resentment Heine describes in “An Edom.” Salten also wrote novellas. Gradually, he became known as a reliable member of the Young Vienna movement. By 1910, he was regarded as one of the best journalists, dramatists, and novelists in Austria.

Salten founded a popular cabaret, wrote plays, produced films, married well, and formed important contacts in all domains of culture. When World War I erupted in 1914, he was initially an enthusiastic promoter of Austria’s struggle against the Allies. Soon, however, he described the war as a catastrophe. By the end, Salten showed great sympathy for the Social Democrats. He became the feuilleton editor of the Neue Freie Presse, and in 1927, he was elected president of the Austrian PEN Club and represented PEN on a trip to America.

Salten is intent on depicting the plight of European Jews caught in an ideological trap after World War I; deer ( Jews) are born to be hunted and killed, and the sooner they learn this lesson, the better able they will be to carve out a life — however brief — for themselves.

With the rise of the Nazis, however, most of Salten’s successes unravelled. In 1933, he was obliged to retire from PEN after an internal struggle with the Nazis, and by 1935, his books were banned in Germany. Salten turned to making films and withdrew from the public. His connections to various members of the Austrian nobility protected him when the country was annexed by the Nazis in 1938. Soon after, he was allowed to emigrate to Switzerland, where he spent the last years of his life dealing with financial problems and writing animal stories. He had a penchant for luxury, and in some ways he sought to live the life of an Austrian aristocrat in his new home. Sadly, he died alone and virtually penniless in 1945, not aware that Disney had adapted his major work into a sweetened mockery of all that he intended to communicate about Jews and antisemitism. Moreover, he wasn’t credited as the creator of Bambi on most of the merchandise connected to the film.

Ironically, Salten himself was a hunter, and highly familiar with forests and animals. It is clear from the beginning of the novel that he is intent on depicting the plight of European Jews caught in an ideological trap after World War I; deer ( Jews) are born to be hunted and killed, and the sooner they learn this lesson, the better able they will be to carve out a life — however brief — for themselves. Bambi is fortunate to be taught by his father, the old Prince, who intercedes on his behalf numerous times. Bambi must learn that he can only depend on himself and on his knowledge of the forest to survive. Even then, survival does not entail fulfillment of any kind. It simply means that Bambi will live slightly longer and more independently than any of the other animals in the forest. Salten demonstrates just how brutal the hunters can be when they capture Bambi’s wounded cousin and nurse him back to health. By the time the cousin returns to his animal friends in the forest, he thinks that he has become one of the hunters’ pets and is invincible. Tragically, he learns the truth when he is later shot by them.

Salten did not mince words: he describes life in the forest as a test of the survival of the fittest. Bambi is not slaughtered in Salten’s novel, for Salten admires him too much as a Jewish stoic hero. Instead, he shows Bambi disappearing, alone, without suggesting that the murder of innocent animals will ever end. Bambi: A Life in the Forest deserves to be read again and again as a critique of antisemitism and a warning that life will always be treacherous for outsiders as they try to harvest and share the fruits of life.

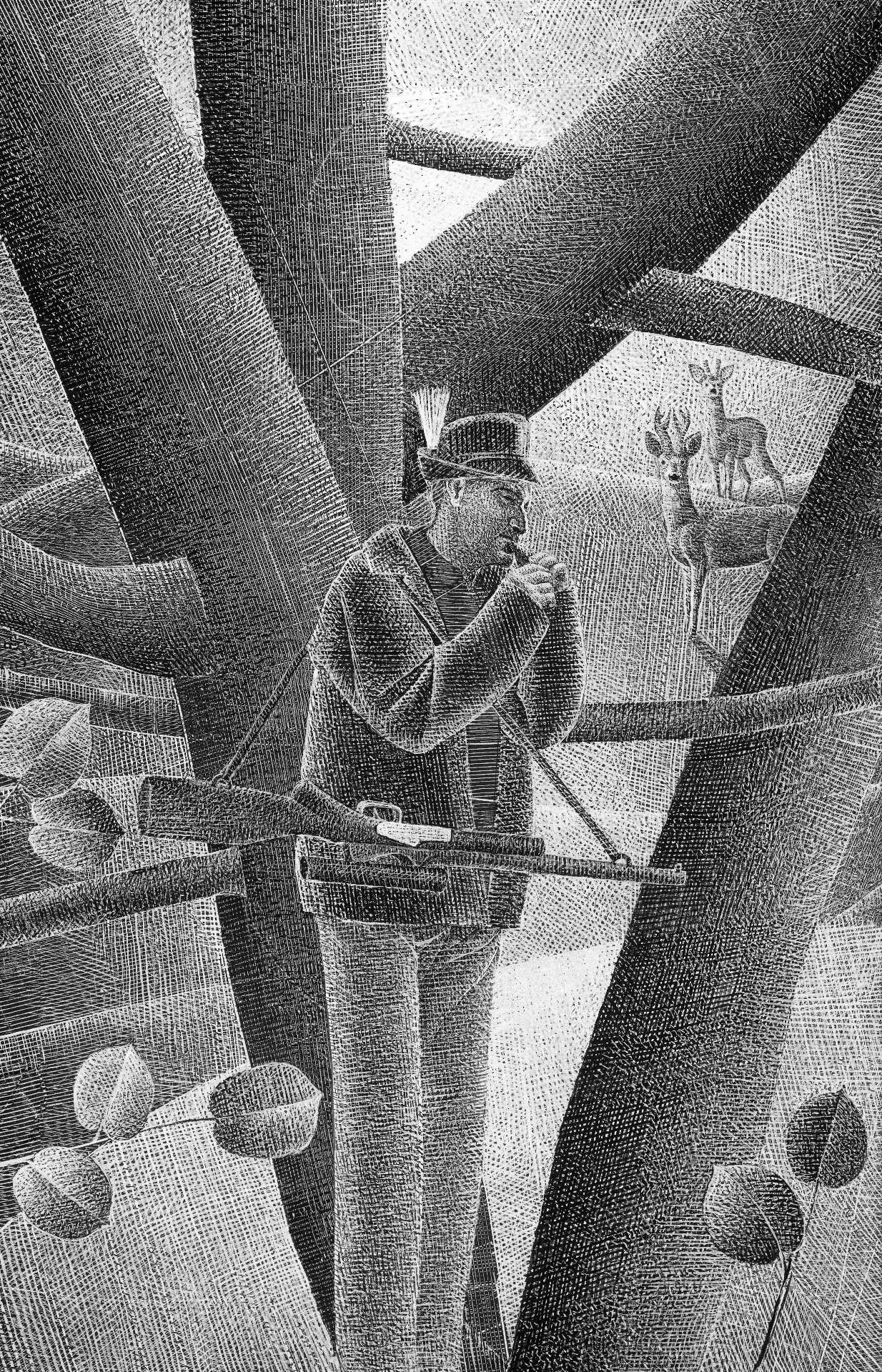

Illustration by Alenka Sottler from The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest translated and introduced by Jack Zipes

Jack Zipes has written, translated, and edited dozens of books, including The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm and The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (both Princeton). He is professor emeritus of German and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota.