Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

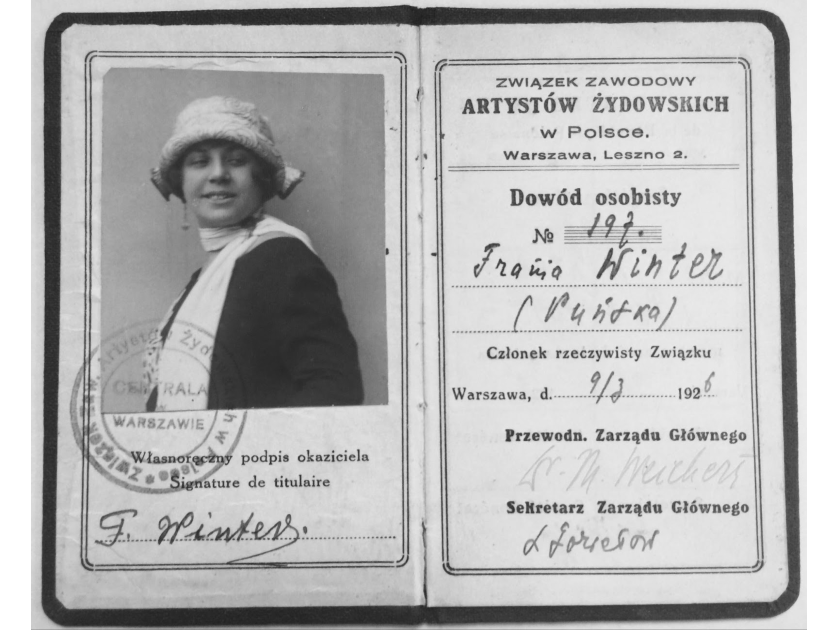

Franya’s Yiddish Actors Union card. Rescued by The Paper Brigade, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NY, NY. Photo courtesy of the author

I don’t remember a time when I was not aware of the Holocaust. I grew up in an American household where there was intentionally little talk of the past, but I understood from a young age that our history was filled with loss.

My parents themselves were not Holocaust survivors, but much of my mother’s extended family had been murdered and disappeared by the Nazis. As a small child, I would dig deep into the recesses of my parents’ TV cabinet and unearth a worn manila envelope full of photographs of these missing relatives. I would pore over sepia-tinted pictures mounted on cardstock while Bewitched played in the background. Many of the portraits were formal, but one person always seemed to stand out in living color: My cousin, a famous actress of the time named Franya Winter. She was featured mugging for the camera in wild costumes, evoking something riotous, playful, even sexy. I was instantly compelled by her. That interest was only enhanced by the fact that her death was a mystery.

Recognizing my attachment to my family’s memory, my aunt Mollie eventually entrusted me with a Yiddish book called, Twenty-One and One, which described the lives and deaths of actors who perished in the Vilna Ghetto – including Franya. “Keep it and pass it onto your children,” my aunt commanded. “But don’t read it.” She never said why.

Thus began my search for knowledge beyond the forbidden book. I would keep my promise to my aunt while unearthing answers to the questions that had plagued me my entire life, and still honoring my family in their death. That quest took me across continents to meet survivors, search archives, and wander the streets my relatives once tread. My search took me to the YIVO archives where I found a cache of essential documents rescued by The Paper Brigade.

—Meryl Frank

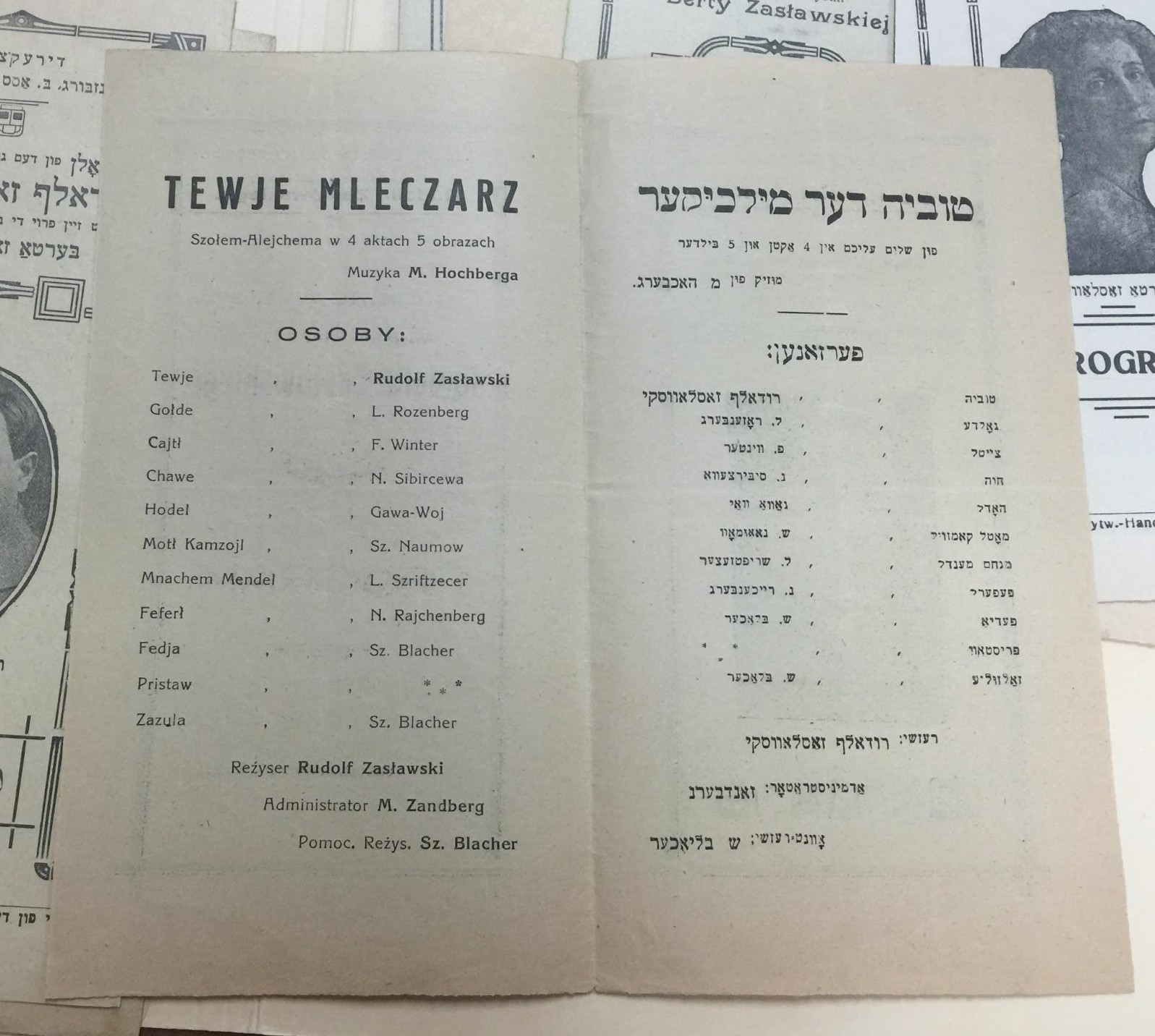

A breakthrough came when I started researching at YIVO, the Yiddish Institute for Jewish Research founded in Vilna before the war, now based in New York, and obtained copies of a significant number of documents relating to Franya — playbills, photographs, and so on.

Most of these had been smuggled out of Vilna in an astonishing operation spearheaded by Vilna intellectuals like Avrom Sutzkever, Shmerke Kaczergynski, and Herman Kruk. They led a team of Jewish workers recruited by the Nazis to go through the cultural treasures of Vilna — including books, manuscripts, and ritual ornaments from the Great Synagogue, from the fabled Straszun Library, from dozens of prayer houses, and from YIVO’s vast collections — and send the most valuable artifacts to Germany. The Nazis were intent on building an unprecedented collection of Judaica as a perverse symbol of triumph over people they were in the process of annihilating. This was a twisted type of memorializing.

Everything came through the YIVO building before being sorted and shipped, and the materials piled up so fast that the number of Jewish workers expanded over a few months from twelve to almost fifty. Sutzkever and his friends concluded, reluctantly, that the books the Nazis had their eye on were probably as safe in Germany as they would be anywhere else as long as the war was raging. But Johannes Pohl wanted only about twenty thousand volumes, one-fifth of the total. The rest was to be sold to paper mills for recycling. So the YIVO workers started smuggling as much material as they could into the ghetto, stashing it in cellars, behind walls, even in holes in the ground.

Sutzkever asked his Nazi boss if he could bring some of the rejected material into the ghetto to burn as fuel, and his boss not only agreed but also wrote a note to ensure that the materials would not be confiscated at the gate. The members of “the Paper Brigade,” as they called themselves, proceeded to slide all sorts of precious materials under their clothing — letters written by the likes of Leo Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky, and Romain Rolland, as well as Theodor Herzl’s diary, the only surviving manuscript written by the important rabbi, the Gaon of Vilna, and so on. Their paper cuts were badges of honor as they stuffed crumpled relics like so much buried treasure beneath their shirts.

To skirt the limitations on how much they could bring out by this method, the brigade also built a secret repository beneath the YIVO building and hid five thousand books and manuscripts there. Other valuables ended up in the basement of a Carmelite monastery around the corner from the cathedral.

One of the Paper Brigade members, Uma Olkenicka, had been the director of YIVO’s Theater Museum before the war. It was likely under her influence that many of the theatrical artifacts, including the records relating to Franya, were scooped out of the trash. Olkenicka was also a talented graphic artist who designed YIVO’s logo and did the artwork for the forbidden book Twenty-One and One. Heartbreakingly, like so many, she did not survive.

Retrieving all the rare books and documents after the war was far from a simple matter. Even after the materials were tracked down and identified, it was difficult to determine where they should go. Veterans of the Paper Brigade were determined to get them to YIVO in New York, where they knew they would be cataloged and protected properly, but they ran into considerable resistance from the US government. It was not until 1949 that most of the Nazi collections, sitting in warehouses in and around Frankfurt, made their way across the Atlantic.

Program for Tevye the Milkman (see F. Winter as his eldest daughter Cajtl.). Rescued by The Paper Brigade, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NY, NY. Photo courtesy of the author

The materials hidden in Vilna proved an even greater challenge. Poet Abraham Sutzkever, one of the original Paper Brigade members, smuggled some out when he traveled to Nuremberg to testify at the war-crimes trials in 1946. By that time, he understood that the Soviets were not likely to value the documents and books. Others he gave in dribs and drabs to a variety of couriers, including members of the American Joint Distribution Committee, the organization for which my aunt Mollie had worked. In one spectacular case, Sutzkever delivered two large bags of valuables to veterans of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The veterans sneaked them across an unguarded section of the Polish-Czech border, carried them to Prague just a step or two ahead of the Czech secret police, and then handed the material back to Sutzkever through the open window of a train as it pulled out of the station headed for Paris. Some, including the collection at the Carmelite monastery, were not recovered and sent to the United States until the 1990s — fifty years later!— when Lithuania was once again free of the Soviet yoke.

By the time I consulted the YIVO archives in New York, I was awed by the stories and by the many acts of bravery that had allowed the documents I was handling to survive. To me, it spoke volumes about the endurance of culture that what was deemed most important to save, despite risking life and limb, was the written word. Even after all the decimation and destruction, the core of Vilna’s Jewish culture shone through — the belief that art and ideas were the greatest treasures.

As I continued my research, I was growing ever more attached to Franya, as if I’d known her. I was now delving into every aspect of her upbringing, her theatrical career, her personal passions, and the many kindnesses she was said to have lavished on others. All of it seemed to dissolve the decades of distance between us and bring us closer.

Adapted from Unearthed: A Lost Actress, a Forbidden Book, and a Search for Life in the Shadow of the Holocaust by Meryl Frank. Copyright © 2023. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

If you want to read more about The Paper Brigade, for whom we have named our annual literary journal, Paper Brigade, learn more with “A Brief History of the Original Paper Brigade” by Lenore J. Weitzman.

Ambassador Meryl Frank (ret.) is an international champion of women’s leadership, human rights, and political participation. She was selected as one of “The Fifty Most Influential Jews in the World” by The Jerusalem Post, and was appointed as the United States Ambassador to the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) by President Barack Obama in February 2009.