Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

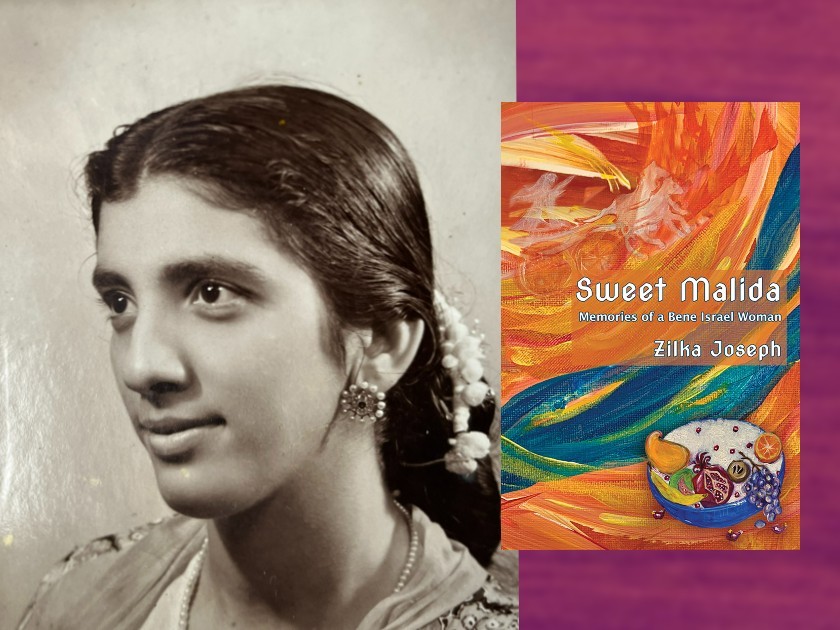

Author’s mother

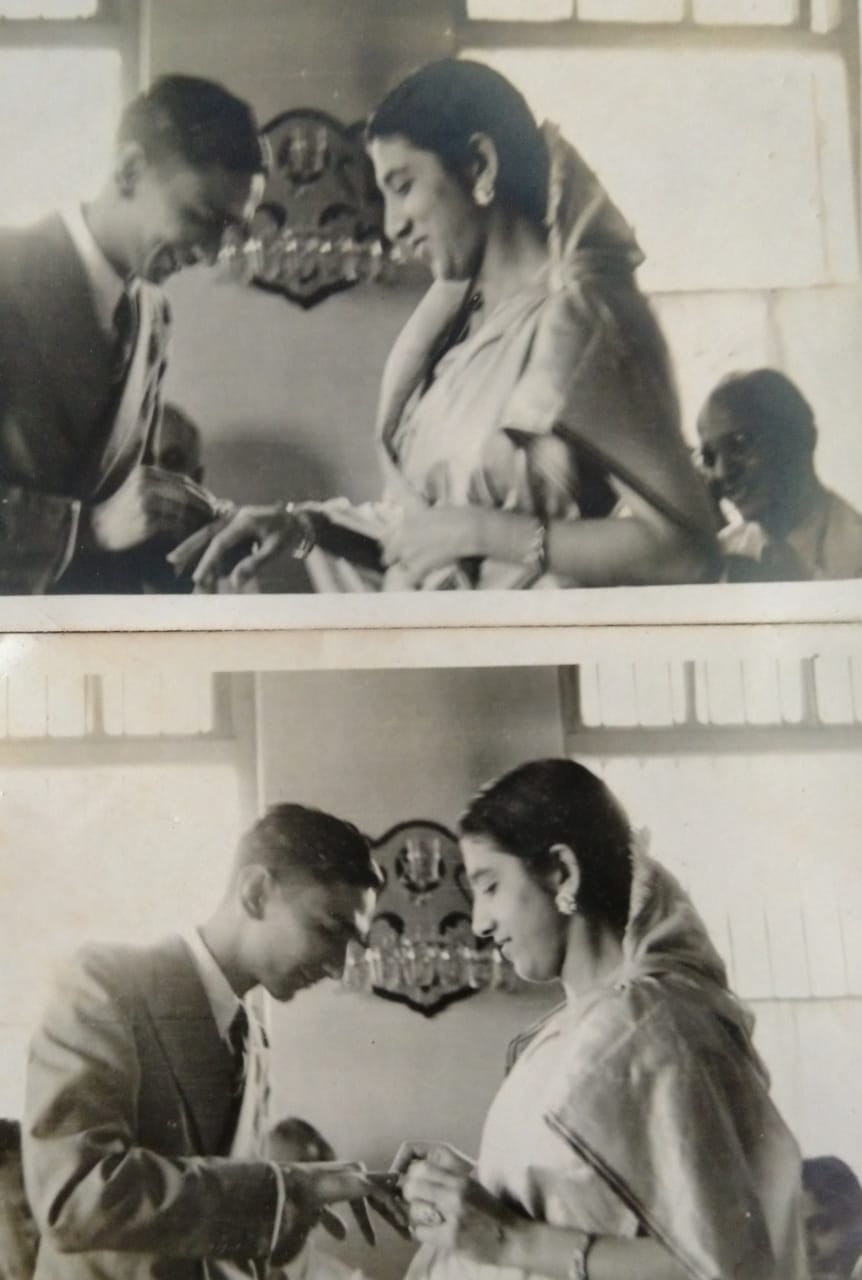

All photos courtesy of the author

Even before my eyes open, my mouth starts watering. The air is thick with the smell of roasting besan and ghee. Oh my, my mother is making besan laadus today. Is it my birthday? I wonder, is it my parent’s anniversary? I roll over and sniff the air.

But the smell is gone. Just like all the other fragrances.

I picture my mother as I’ve seen her in photographs taken before I was born. My mother, young and beautiful. She has glowing skin, large eyes, well-defined eyebrows, and a big nose — a feature which I have inherited. She has very long hair, braided in a plait that reaches below her knees. I never saw her hair worn like this. And I imagine the photographs I’ve seen of tables laid out for Shabbat prayers and dinner at her parents’ home. The polished brass Star of David oil lamp, lace tablecloths, platters of fruit, and small cups of raisin sharbath.

So much of my childhood memories are fading, but the tastes never do. Neither do the smells, the smiles or the sorrows. My body is the vault that holds these histories, these precious memories. They are mine and mine alone. No one else in our family will remember the same things or remember them the same way, even if they were present at the same time and place.

Here is what I remember.

My mother’s hands are quick as she stirs the dried channa — split chickpeas, in the tava. From a pale yellow, they turn to beige, to gold-brown. Then she grinds them by hand till they turn into a medium-fine powder. A few crunchy pieces remain. She adds this ground besan to a large flat-bottomed karahi where the ghee is already warmed and ready. Stir, stir, stir. She wipes her forehead with the edge of her Calico sari pallav. My grandmother has come to check if she is doing it right. My granny is a tough bossy woman who takes over my mother’s life after she marries my father.

It is time to shake in the sugar little by little. The greyish crystals are large and crunchy and not all of them melt completely. Stir, stir, stir. Slowly, it is all coming together. The aroma is thick and sweet and spreads all over the house, wafting from our balcony to others, blown by the breeze down the street. The crows hang around our kitchen window. Today they seem antsier than other days. So am I, as I wait for the rituals to be over. They will get their share too.

The author around age three, with her grandmother Hannah Joseph

Now my mother adds the fried raisins and cashews into the almost-pliant, almost-sticking- to-the-pan mixture. Earlier that day, she has picked the raisins and cashews through for stones and they have been washed and air-dried. Still, it is not unusual for a grain of sand to hide in a crevice somewhere and appear suddenly under your molar when you are eating. Ouch. The pleasure and the pain. Inseparable, sometimes.

Granny is inspecting the mixture with her fingers. It’s time to taste. Yes! My turn now. Have you washed your hands? Yes, yes, yes. I drop a blob on my tongue. Mmmm, Granny says as she does the same. Now we all dig in with our hands. Not to eat, but to roll the sticky-crumbly mixture between our palms. We form lime-sized balls and lay them out on a tray to harden. Then we will arrange them in our big steel dubbas. Some we will distribute to our neighbors and friends. But the rest is ours. For now we keep rolling, rolling, rolling. How I long to lick my fingers as we do this, but they are watching my every move, so I don’t. The reward is exquisite, so I will wait patiently. I can handle the wait. I am grown up now. Or so I think.

I will wait for the laadu to be ready, this gold globe that is made by their hands. I will bow my head and open my palms to receive it. A world held in their hands, then placed in mine. Heavy and earthy in my palms. Its deep and nutty flavor coats my tongue as I stand here at the edge of memory. This is not a figment of my imagination. It’s what makes it all real. That the joy existed. That my parents, Ruby and Sunny, existed, and my grandma Hannah, existed. That love wrapped around me like these aromas. That my mouth and tongue are blessed by them. Goud-goud bolah, they say in Maharashtra on some Hindu festivals when they feed you spiky little beads of sugar and sesame seeds. Speak only sweet words. The wise hearts of the laadu makers taught me — good thoughts, good words, good deeds.

And what of contentment? They blessed me with that too. No matter how little or how much I may have or how my situation may change from year to year, I, laadu eater, bow humbly to the ones who made me who I am, who sacrificed and never asked for thanks, and whom I never celebrated enough. And I ask for their forgiveness, for all of those things, but most of all for not writing down their recipes, their magic words.

Engagement photos of the author’s mother and father

Zilka Joseph was born in Mumbai, and lived in Kolkata. Her work is influenced by Indian/Eastern and Western cultures, and her Bene Israel roots. She has been nominated several times for a Pushcart, and for a Best of the Net, has won many honors, participated in literary festivals and readings, and has been featured on NPR/Michigan Radio, and several international online interviews and journals. Her work has appeared in Poetry, Poetry Daily, The Writers’ Chronicle, Frontier Poetry, Kenyon Review Online, Michigan Quarterly Review, Beltway Poetry Review, Asia Literary Review, Poetry at Sangam, The Punch Magazine, Review Americana, Gastronomica, and in anthologies such as 101 Jewish Poems for the Third Millennium, The Kali Project, RESPECT: An Anthology of Detroit Music Poetry, Matwaala Anthology of Poets from South Asia (which she co-edited), Cheers To Muses: Contemporary Works by Asian American Women, Uncommon Core: Contemporary Poems for Living and Learning, and India: A Light Within (a collaborative project). She was awarded a Zell Fellowship (MFA program), the Michael R. Gutterman award for poetry, and the Elsie Choy Lee Scholarship (Center for the Education of Women) from the University of Michigan. Her previous Mayapple books are Lands I Live in (2007) and In Our Beautiful Bones (2021). Zilka teaches creative writing workshops in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and is a freelance editor, a manuscript coach, and a mentor to her students.