Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Lavie Tidhar’s most recent book, An Occupation of Angels, is now available. He will be blogging all week for the Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning‘s Author Blog.

I’ve got a feeling that, in years from now, with many novels, novellas, and collections all out (I’ll have 3 novels out just next year, if it’s an indication), when oil becomes scarce and there’ll be a Chinese colony on the moon, I’ll still be that HebrewPunk guy.

I’ve got a feeling that, in years from now, with many novels, novellas, and collections all out (I’ll have 3 novels out just next year, if it’s an indication), when oil becomes scarce and there’ll be a Chinese colony on the moon, I’ll still be that HebrewPunk guy.

I should probably explain…

A few years ago, I became irritated enough with fantasy fiction to do something about it. When I get asked about it, I normally say it was the vampires what did it. It used to drive me insane that the underlying assumption of – well, pretty much all – vampire novels and movies, was that Christianity worked.

After all, we all know what vampires are afraid of. Crosses and holy water, right?

Which is strange, and a little uncomfortable, if you happen to be Jewish.

Because, like the Aryan elves of fantasy literature, there is a whole planetary mass of underlying assumptions of cultural dominance behind those “silly stories about unreal things”. And Jews don’t belong, they seem to say, in fantasy.

This goes back a long way, of course. The most important editor of American science fiction was John W. Campbell, revered to this day, with a bunch of awards named after him. By all accounts he was a lovely, if somewhat eccentric, guy (he launched L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics – later Scientology – in a 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, after all). There was only one thing about Campbell – he thought the best people were white, west European people, and he felt that the “readers” wouldn’t appreciate Jewish names in his magazine. Isaac Asimov, the most famous Jewish SF writer to this day, writes about it in his autobiography – and how lucky he was to get published under his own name – but at least one other writer wasn’t so lucky. Jews could write this kind of stuff, as long as they weren’t too Jewish.

I mean, no one wants that, right?

And so, back to vampires, afraid of Christian symbols, afraid of water blessed by a priest.

What if, I thought, you had a Jewish vampire? He wouldn’t be afraid of this stuff, surely?

‘That sounds awfully racist!’ my mother told me when I happened to mention it to her. ‘Like the worst blood libels, all the things that were attributed to Jews throughout the years!’

Which was partly the point, of course. I wanted to re-claim fantasy. I wanted to play with the idea of the Jew-as-blood-drinker, the awful racial stereotypes, and at the same time with the underlying assumptions of white, Christian superiority in generic fantasy fiction at the same time.

A few years ago, too, I ran into Neil Gaiman at the time of his American Gods launch. Every kind of fantasy archetype is in there, but for one. ‘Where are the Jews?’ I asked, and watched him squirm a little and finally say, ‘Well, there’s a golem in it. What else is there?’

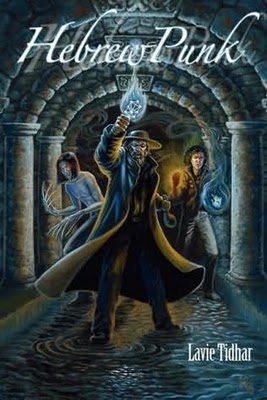

So I wanted to answer that question, too. What else is there? And I didn’t want to write a mainstream, literary novel. I wanted to write pulp. I wanted to re-imagine pulp fantasy in a different universe. As one reviewer said on reading the eventual product, my mini-collectionHebrewPunk, the stories read as though they had appeared in the 1940′s in magazines such asYiddish Excitement Quarterly andThrilling Hebrew Tales!

But of course, we didn’t have those magazines. The Yiddish pulps had all but disappeared, and Jewish literature became concerned with heavy matters, with the realistic approach, with issues. The issues I was interested in were those that came into your post box every month with a picture of a monster on the cover.

So I set out to write what would become HebrewPunk.

****

I only slipped once. I ended up going literary with the last story. At least, I think I did.

****

The first story came seemingly complete. It was called “The Heist”. It was, as the title suggests, a heist story (I wanted each story to fit a very specific genre). It was pulp, almost comics-like, almost drawn rather than written. It introduced a gang of immoral, underworld figures: the Rabbi, who had the power to make golems; the Rat, my Jewish vampire (and we all remember the rats in Fritz Hippler’s Nazi “masterpiece” The Eternal Jew, right?); and the Tzaddik, a renegade from the Lamed-Vav, the 36 righteous men of Jewish legend.

The first story came seemingly complete. It was called “The Heist”. It was, as the title suggests, a heist story (I wanted each story to fit a very specific genre). It was pulp, almost comics-like, almost drawn rather than written. It introduced a gang of immoral, underworld figures: the Rabbi, who had the power to make golems; the Rat, my Jewish vampire (and we all remember the rats in Fritz Hippler’s Nazi “masterpiece” The Eternal Jew, right?); and the Tzaddik, a renegade from the Lamed-Vav, the 36 righteous men of Jewish legend.

Three anti-heroes, hired for a job no one else wanted to do. It didn’t have much of a plot. I had fun devising a blood bank guarded with holy water sprinklers and crosses cut into the walls (no match for my guy!), assembling my team, and sending them off on one last mission, and, o course, nothing quite works out as it’s supposed to.And once I had finished it, I knew – at that very moment – that each of these characters required their own story.

I next took the Rat back to his earlier days in “Transylvanian Mission” – a World War II story with Jewish partisans, an elite Nazi commando unit made of werewolves (naturally!), and the Nazi quest to awaken Vlad Tepes, AKA Dracula, from slumber. It was easy to write – my family comes from Transylvania, and in the mountains one might still see the name Heisikovitz on a tombstone (my original family name). And the Nazis notoriously did hunt for mythical objects and were obsessed with the occult. So I got to have fun with that.

My Tzaddik ended up in 1920 London, a time of Jewish gangsters, of a roaring drug trade… and of rampant racism. As it happened, it was also my breakthrough story, since it sold – rather to my amazement – to Sci Fiction, at the time the highest-paying, highest-profile genre magazine in existence (it was sponsored by the Sci Fi Channel). I got a big check for that one…but then the corporate bosses pulled the plug, and “The Dope Fiend” was the last story ever published there.

Make of that what you will.

The stories were published individually, but I always knew they were meant to be gathered together. I finally pitched the idea to Jason Sizemore, head of a small publishing house in the U.S., Apex Books, and he thought it was worth giving it a shot. I sat down and wrote the final story, “Uganda”, which follows my rabbi in 1904, following a visit from Herzl himself, and joining the Zionist Expedition to British East Africa to decide on the suitability of that area for possible Jewish colonization…

And here, I think, I sinned. Because, while it is pulp, glorious pulp, it also became something of a statement, an examination of Jewish states, and a comparison of sorts with the one we did end up with in British Mandate Palestine instead…

I was able to view – and later, incorporate into the text – the actual expedition report, a story far stranger, and more fascinating, than anything I could devise. In fact, with each of the stories, I delved deep into the actual history – whether it was the desperate war against the Nazis in ’43, or the hidden world of Jewish gangsters in 1920, or the strange, forgotten expedition to Africa on behalf of the Zionist Congress in 1904. Because being Jewish is being a part of history – a secret history, a forgotten history, a lot of the time – as though Jews were the notes scribbled on the margins of history, faint but always there when everything else passes and is gone forever.

The book, at last, was published. It had a suitably garish, pulpy cover (by the awesome Melissa Gay) which truly belonged on the cover of Thrilling Hebrew Tales. We weren’t sure about the title – HebrewPunk was meant tongue-in-cheek, but I saw several people miss out on the irony – but we went for it nevertheless. It sold – moderately – and continues to sell (moderately). And it made its way into the pages of none other than the Encyclopaedia Judaica (if only in passing mention). You know you’ve made it when you’re in that book!

And if I get to be remembered for anything, and it just happens to be for HebrewPunk, I don’t think I’d mind too much.

Lavie Tidhar’s HebrewPunk is available on Amazon in paperback and Kindle editions. His first novel, The Bookman, is out now, and will be followed next year by Camera Obscura.

Lavie Tidhar (A Man Lies Dreaming, Unholy Land) is an acclaimed author of literature, science fiction, fantasy, graphic novels, and middle grade fiction. Tidhar received the Campbell and Neukom Literary awards for his breakout novel Central Station, which has been translated into more than ten languages. He has also received the British Science Fiction, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Awards. Tidhar’s recent books include the Arthurian satire By Force Alone, and the series Adler. He is a book columnist for the Washington Post, and recently edited the Best of World SF anthology. Tidhar has lived all over the world, including Israel, Vanuatu, Laos, and South Africa, and he currently resides with his family in London.