Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

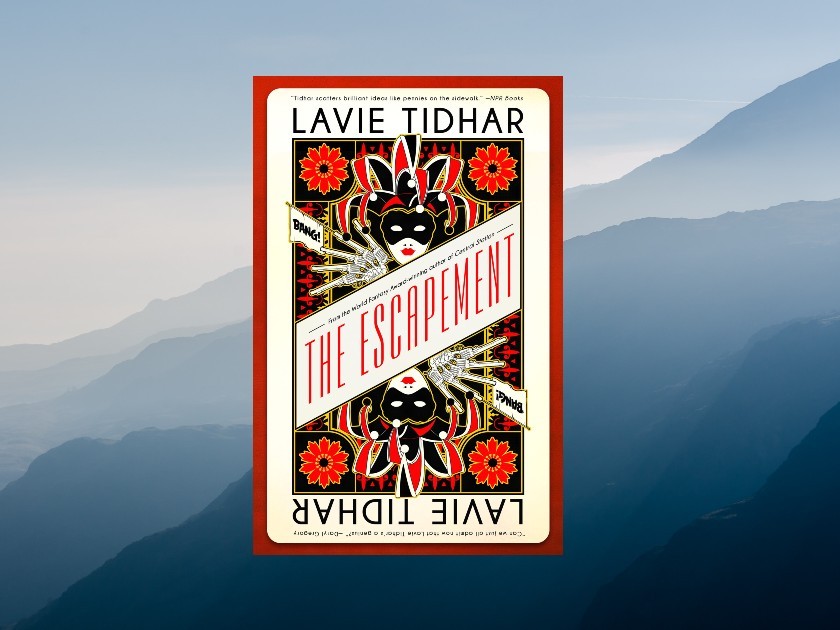

After a string of pretty Jewish books—A Man Lies Dreaming, Unholy Land, Central Station (the only novel, I think, to feature a detailed bris carried out by a robot mohel) — it felt like a relief to write something that was very, honest my Lord, totally not Jewish in any way like The Escapement.

Only I’m not sure that’s quite right.

The fairy tale I was inspired by is called “The Flower of the Golden Heart.” It’s a fairy tale about a boy whose mother is ill and he goes in search of a flower far away — behind the distant mountains —which is the only thing that can cure her (in my version of the story, a father goes riding in search of a flower for his ailing son). It’s an incredibly well-known fairytale in Israel and, like many others, I’d have assumed it originated in Europe somewhere, perhaps written by Andersen. The catch is that it wasn’t. Detective work will tell you it was composed by a fairly obscure Hebrew writer, Shlomo Zalman Ariel. Similarly, the Mountains of Darkness — behind which I placed my mythical flower — were inspired by the Alexandrian tales of the Talmud, which were favourites of my grandfather. If you don’t know them, they are a collection of legends about Alexander the Great, told by Chazal.

But The Escapement is a novel that owes as much a debt to the Marx Brothers and Harry Houdini as to fairy tales of old. A conjurer is one of the main players in the novel, and I have a love of stage and performance magic that goes back years. I have a conviction that Harry Houdini (born Erich Weisz) and I are related. The Weisz family were Hungarian, and my grandfather as a young man bore a striking resemblance to the young Erich Weisz. Please do not disabuse me of the notion.

I have a conviction that Harry Houdini (born Erich Weisz) and I are related. The Weisz family were Hungarian, and my grandfather as a young man bore a striking resemblance to the young Erich Weisz.

Jews made their way to entertainment — to vaudeville and then the nascent film industry — partly by necessity, I think. It was a profession open to new immigrants to the United States in a way that other avenues weren’t.

So the world I populated for my hero to travel in is a world of clowns, stage magicians, and comedians. A world of circuses and entertainers. Nothing Jewish about that…

There’s a place on the Escapement called Geller’s Bend, in homage to the magician Uri Geller. There’s a place called the Copper Fields, named for another famous magician. There’s the Chagrin river, named for the British-Israeli mime Julian Chagrin. There’s a town named Bozoburg; TV’s first Bozo the Clown was Frank Avruch, and he must have been the hardest working Jewish clown in the world.

My other 2021 novel, The Hood, just came out in England. It was partly inspired by discovering the figure of Rebecca and her father, Isaac of York, in the classic Robin Hood novel Ivanhoe by Walter Scott; I realised there really were Jews in Medieval Nottingham. What were Jews doing in Nottingham in the twelfth century? As it turns out, they were brought over to England from France by William the Conqueror and served as the king’s moneylenders. They were legally defined as “property of the king.” It was not exactly an easy life. But I got some mileage out of having a Jewish character stuck in a Robin Hood story while knowing she had no place in it— and rather hating the whole thing!

But I digress.

Of course, digression is itself a part of the fabric of The Escapement; a part, too, of Judaism. In The Escapement, the Stranger’s path to the Mountains of Darkness is not a linear one. Like one of my grandfather’s stories, it takes rather a while to get there. For Jews as story-tellers, the joy is in the twists and turns, the side quests, and the blind alleys. And so the Stranger, like a Wandering Jew, is doomed to follow the paths of the maze. “The Stranger had been travelling for a long time, and was to travel for a long time more,” the Escapement’s narrator keeps reminding us. Mazes form a part of the world of the Escapement— how to navigate them and how to escape become a refrain in itself. Just as the question of escape into the imagination keeps running like a refrain through my work.

And then, of course, there is the matter of the clowns. Hated, persecuted, grotesque in their appearance: they are loathed by everyone on the Escapement but for the Stranger. It’s hard, in hindsight, not to see they could stand in for the persecuted Jews, aliens wherever they go, presented as grotesque caricatures. Is The Escapement about that? I don’t know. Are the clowns Jewish, just as Jews were clowns? Only recently I came across the very strange 1953 film The Juggler, about a Holocaust survivor and former performer on the run in Israel— the first Hollywood film ever made there.

I started out writing this piece convinced there was nothing Jewish about this novel, but having reached the end, I’m not so sure it’s true.

I am curious to know what readers think.

Lavie Tidhar (A Man Lies Dreaming, Unholy Land) is an acclaimed author of literature, science fiction, fantasy, graphic novels, and middle grade fiction. Tidhar received the Campbell and Neukom Literary awards for his breakout novel Central Station, which has been translated into more than ten languages. He has also received the British Science Fiction, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Awards. Tidhar’s recent books include the Arthurian satire By Force Alone, and the series Adler. He is a book columnist for the Washington Post, and recently edited the Best of World SF anthology. Tidhar has lived all over the world, including Israel, Vanuatu, Laos, and South Africa, and he currently resides with his family in London.