Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

“I didn’t think he’d do it. I really didn’t think he would.” That’s how I open my book, with a short “midrash” – a short readers and writer’s response to the story in the context of all the Abraham stories that come before.

“I didn’t think he’d do it. I really didn’t think he would.” That’s how I open my book, with a short “midrash” – a short readers and writer’s response to the story in the context of all the Abraham stories that come before.

And then, in the next chapter, I introduce the author of Genesis 22 and the writing of the story. Those pages are pure speculation. No one knows for sure who wrote those nineteen lines of scripture, let alone what he (I explain much later in the book that no one thinks the story was written by a woman) was thinking as he wrote, let alone his interaction with his editors or his wife, or even when the story was written or what parts of the cycle of Abraham stories (of which it is the climax) were written before (in my version it is late to the Abraham cycle) and what parts were written afterward.

Jane Smiley called those pages amusing and shameless, and I would add wholly anachronistic. There is, I believe, plenty of literary and figurative truth in them, starting with the first line of Chapter 2 (“He was a writer”: no one who appreciates the story as a story would deny that) but the historical truth comes later.

And already people are asking why? Why open a non-fiction book with speculation. The answer is pretty simple: The subject is as close to infinite as a subject can get. In a book of 250 pages I have probably not even sampled one percent of one percent of the exegesis that’s been translated into English, and the vast majority of it probably hasn’t been translated into English. My book moves chronologically but it is less a survey than a series of soundings. There is, inevitably, a lot of repetition, and for it not to be tedious (or more tedious than it is) it had to be written from a point of view.

But what point of view? I struggled with that question for years, and in fact I probably have more than half a dozen versions (not drafts, but very different versions) of the opening 30 pages, the pages which I establish the narrator’s point of view and voice. They are still on my hard drive. One is simply from my point of view, James Goodman, writer and professor of history, from soups to nuts. But I was never happy about the way that version sounded, the way I sounded as narrator. It was too serious, too straight, too stiff. One is from the point of view of the author of the story, an author who feels he wrote a pretty straightforward story about obedience to God. He likes the story, which makes it all the more frustrating as he discovers that every Tom, Dick, and Harry (or Jubilees, Philo, and Josephus) feels free to revise it, add characters and dialog and scenes and thereby twist the story and its meaning in every imaginable way, including versions in which Isaac actually dies. Another is from four points of view, Abraham, Isaac, Sarah, and God. There are, alas, others.

In the end I settled on the perspective of writer (and reader, since all writers are the first readers of their own work) who thought the author got the story wrong and who wanted to revise it. He is not able to revise it (for reasons you need to read those pages to understand). So he pins his hope on (and takes some consolation from) the idea (provided by his wife) that the story will ultimately be revised by others. “Someone will revise it,” she says. The perspective of a writer who thought he got the story wrong provided the moral center I wanted (grave reservations about the story) as well as the tension I wanted (Was she right? Would the story actually be revised? If so, how, when, and why?). It also provided the forward momentum I thought my narrative needed (as I watched the history or life of the story unfold).

“But where,” my real wife asked recently, when she started reading the book, for the first time, “did your narrator’s voice come from? Who is it? I like it, but it isn’t you.”

“No, I said it isn’t.”

“It never is,” she said. “But this one is more so.”

“I think that’s right, I said.” My narrator is, like all narrators and then some, a character all his own, some amalgam of voices, a writer, a reader, a father, a historian, a skeptic, and a Jew.

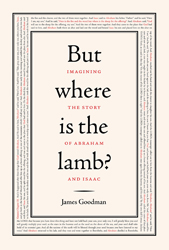

James Goodman is a professor at Rutgers University, where he teaches history and creative writing. His most recent book, But Where Is the Lamb?, is now available. He is also the author of two previous books, including Stories of Scottsboro, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Keep up with him here.