Lenore Weiss’s most recent collection,Two Places, is now available. She is blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

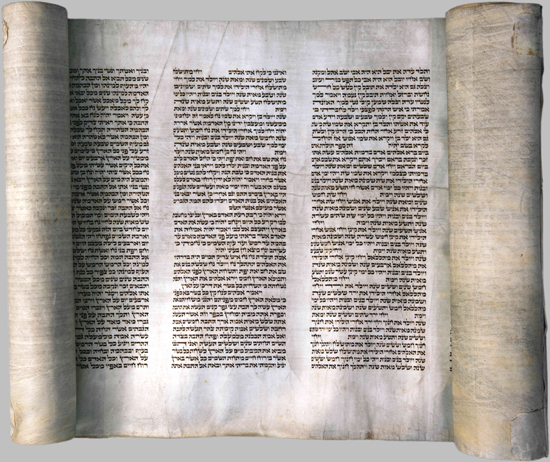

With a ready smile, Rabbi Levi Selwyn stood behind a Torah that is spread open on a long bridge table at Temple B’nai Israel in Monroe, Louisiana. Congregants and community members faced him on the opposite side of the table as he discussed the repair of two Torahs belonging to this northeastern Louisiana synagogue of approximately seventy-five families.

A member of Sofer On Site based in Miami, Florida, Rabbi Selwyn was born in London and has served as director of youth programs in the United States and as the Chief Rabbi of the Newtown Synagogue in Sydney, Australia.

He explained how he “Koshers” Torah scrolls — it’s not unusual for scrolls to have traveled across climates and borders to reach their current homes, he said. Some can be more than a hundred years old. Scrolls can be neglected; especially if a congregation is lucky enough to have several Torahs, but reserve a few for special occasions. Over time, parchment can deteriorate, become hardened, discolored, and letters can crack. That’s a job for Rabbi Selwyn who evaluates the condition of each Torah and takes his cues from there.

The basic Torah repair kit consists of parchment (cowhide), ink, and sinews that are used to sew together each section. Suppliers sell these specialized materials and are based in Miami and Israel. Inks are of a certain consistency; their mixture can include iron sulfate, gum Arabic and sometimes honey. Like a secret sauce, approximately four to five families hold the recipe and have been providing these inks for generations. As prescribed by the Torah, the color must be black.

Rabbi Selwyn brought along a collection of quills that he uses to repair the letters, white feathers from domesticated turkeys (they tend to be larger), and also chicken feathers. Each quill is cut by hand to absorb enough (but not too much) ink, allowing the sofer (scribe) to form Hebrew letters, and match them to the original Torah. Rabbi Selwyn explained how Torahs employ different styles of writing, which include Beit Yosef, often used by Ashkenazi communities, AriZal, Kabbalist in its origin, and Vellish, often used by Sephardic communities.

Frequently, a sofer will need to scrape the parchment to allow for letters to be rewritten or reformed correctly. Older Torahs, he explained, are glazed on their unwritten side. As a result, material can rub off onto the letters. For this purpose, he keeps a high polymer eraser handy and an Exacto knife for scraping parchment. Elmer’s glue also plays a role, especially when a sofer needs to cut and paste an entire word or section. Rabbi Selwyn shares that once he found a tic-tac-toe board written in the margins of a Torah. Of course, it had to be scraped.

There are thousands of laws governing the scraping and writing and about everything else concerning the repair of Torah. A certain amount of white space must surround each letter. Letters are repaired based upon the ability of the reader to see them from an appropriate distance, although a magnifying glass may be employed to reform the writing of YWVH’s name. Four empty lines separate each book, and in case you’re wondering, the Torah contains a total of 304,805 letters, letters that originally spoke everything into existence in white and black flames.

Read more of Lenore Weiss’s work here.

Related Content:

- Essential Torah: A Complete Guide to the Five Books of Moses by George Robinson

- The Torah: A Women’s Commentary edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L Weiss

- The Everyday Torah by Rabbi Bradley Shavit Arson

- Text Messages: A Torah Commentary For Teens edited by Rabbi Jeffrey K. Salkin

Lenore Weiss’s most recent collection, Two Places, is now available. Read more of Lenore’s work here.