Lesbian-feminist poet and scholar Julie R. Enszer blogs this week for The ProsenPeople on the seminal Jewish lesbian voices of the previous generation and the process behind her own writing. Her second collection of poetry, Sisterhood, comes out this week.

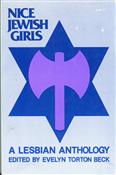

As my second collection of poetry Sisterhood publishes this fall, I have been thinking about books from the past that made it possible for me to write Sisterhood. One of these books is Nice Jewish Girls, edited by Evelyn Torton Beck and published in 1982.

As my second collection of poetry Sisterhood publishes this fall, I have been thinking about books from the past that made it possible for me to write Sisterhood. One of these books is Nice Jewish Girls, edited by Evelyn Torton Beck and published in 1982.

Writers are readers, first and foremost. For many of us, we, initially, write our books on the pages of other books, as though our books are a midrash, squeezed between the words and lines of other texts. We imagine ourselves part of a vibrant simultaneous dialogue with books and authors, alive and dead, written and emerging; we imagine that our book extends stories from other books, speaks directly to characters echoing in our minds. As if by magic, words flit across our manuscript page from other sources re-formed, re-shaped, and re-written into our own book. In this way, all books mimic the dialogue of midrash: one writer speaking to another or hundreds of others, each book speaking to earlier ones, words and images layered upon the past, a cacophony of voices distilled into sequential words on single, orderly pages.

In Judaism, midrash elaborates the Tanakh, but lesbian-feminists have no Urtext for perpetual return. Rather, lesbian-feminism is a constantly unfolding text; lesbian-feminism is a concatenation of theories, philosophies, communities, and lives lived. While there are no Urtexts, there are books that are touchstones, books to which I repeatedly return, books for which I am grateful, books to which I am always responding, books into which I try to write myself.

Nice Jewish Girls is one of those books. The conditions of anti-Semitism in lesbian-feminist communities and homophobia in Jewish communities motivated editor Evelyn Torton Beck to imagine and create the anthology Nice Jewish Girls in the early 1980s. Persephone Press, an independent, lesbian-feminist publisher, published the first edition of Nice Jewish Girls. After that first edition, two other editions of Nice Jewish Girls circulated — one from The Crossing Press in their “Feminist Series” and another from Beacon Press. Nice Jewish Girls stayed in print throughout the 1990s, a lodestar for many, including me.

Nice Jewish Girls is one of those books. The conditions of anti-Semitism in lesbian-feminist communities and homophobia in Jewish communities motivated editor Evelyn Torton Beck to imagine and create the anthology Nice Jewish Girls in the early 1980s. Persephone Press, an independent, lesbian-feminist publisher, published the first edition of Nice Jewish Girls. After that first edition, two other editions of Nice Jewish Girls circulated — one from The Crossing Press in their “Feminist Series” and another from Beacon Press. Nice Jewish Girls stayed in print throughout the 1990s, a lodestar for many, including me.

During the first half of the 1980s, feminist presses published a variety of Jewish lesbian novels, including Alice Bloch’s The Law of Return (1983), Ruth Geller’s Triangle (1984), and Sarah Schulman’s The Sophie Horowitz Story (1982). Nice Jewish Girls, however, distilled the identity of Jewish lesbians. Nice Jewish Girls includes the work of an array of writers including Irena Klepfisz, Elana Dykewomon, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, Rachel Wahba, Maida Tichen, Susan J. Wolfe, Judith Plaskow, and Martha Shelley.

Nice Jewish Girls was a generative text; it nurtured new voices and sparked conversations between and among Jewish lesbians. Speaking directly to Nice Jewish Girls, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz published Tribe of Dina, initially as an issue of Sinister Wisdom and later as a book; Tribe of Dina responded to Nice Jewish Girls in productive ways, thinking particularly about relationships between U.S. lesbians and the state of Israel. Nice Jewish Girls also inspired a new generation of writers, who published — or continuing to publish — in the early 1990s, including Judith Katz’s Running Fiercely Toward a High Thin Sound (1992), Lesléa Newman’s Good Enough to Eat (1986), Anna Freud Loewenstein’s The Worry Girl (1992), Sarah Schulman’s Empathy (1992), and Jyl Lynn Felman’s Hot Chicken Wings (1992). Nice Jewish Girls articulated a Jewish lesbian subject position and generated activism and literary work from that subjectivity.

A few years ago, I had the extraordinary pleasure of meeting Evelyn Torton Beck in person to talk about her work in Nice Jewish Girls. I revered Beck’s many contributions as an activist and scholar; my awe grew while talking with her. In the dozen years since her retirement from the University of Maryland, where she was a professor of Women’s Studies, Beck earned another PhD in Clinical Psychology, published numerous essays on topics that extend from clinical psychology to art, developed a new expertise in aging, and conducted classes on dancing and creative aging. It is not surprising that the woman who helped to articulate and synthesize Jewish lesbian identities continues to live in the world in a dynamic, engaged, and joyful way. May I be so bold as to hope for the same?

A few years ago, I had the extraordinary pleasure of meeting Evelyn Torton Beck in person to talk about her work in Nice Jewish Girls. I revered Beck’s many contributions as an activist and scholar; my awe grew while talking with her. In the dozen years since her retirement from the University of Maryland, where she was a professor of Women’s Studies, Beck earned another PhD in Clinical Psychology, published numerous essays on topics that extend from clinical psychology to art, developed a new expertise in aging, and conducted classes on dancing and creative aging. It is not surprising that the woman who helped to articulate and synthesize Jewish lesbian identities continues to live in the world in a dynamic, engaged, and joyful way. May I be so bold as to hope for the same?

I return to Nice Jewish Girls regularly, for inspiration, solace, and stimulation. Many of the poems in Sisterhood fit into the cracks, between the words, amid the sentences of Nice Jewish Girls. Sisterhood speaks to the women who wrote Nice Jewish Girls, sometimes with force, sometimes with trembling. My own small hope is that someday Sisterhood will be a meaningful part of Jewish lesbian herstory like Nice Jewish Girls; I hope that Sisterhood may be a touchstone text for a Jewish, lesbian writer in the future.

Julie R. Enszer is the author of four poetry collections, including Avowed, and the editor of OutWrite: The Speeches that Shaped LGBTQ Literary Culture, Fire-Rimmed Eden: Selected Poems by Lynn Lonidier, The Complete Works of Pat Parker, and Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker 1974 – 1989. Enszer edits and publishes Sinister Wisdom, a multicultural lesbian literary and art journal. You can read more of her work at www.JulieREnszer.com.