As Emily Bowen Cohen demonstrates in this graphic novel based on her own life, belonging to two tribes is not always easy.

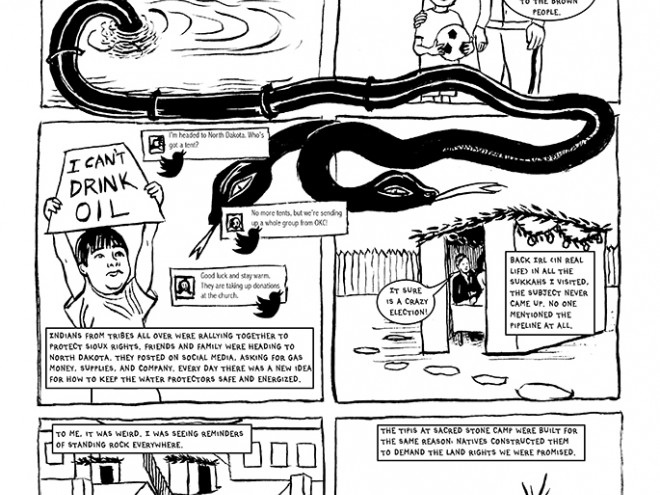

Mia is about to celebrate her bat mitzvah. Her Jewish mother and her Muscogee father are divorced, and the two sides of her heritage seem to conflict with one another. At Mia’s Jewish day school, students make ignorant assumptions about her ethnicity, and her Jewish stepfather’s attempts to unify their family are well-meaning but often awkward. Mia develops a plan to leave California and visit her father in Oklahoma without her mother’s permission.

Cohen depicts how anguish, defiance, and love coexist in Mia’s struggle to determine who she is. Mia’s coming-of-age is both unique and representative. The failure of her parents’ marriage has left her with dual loyalties. Her mother is returning to Jewish religious practice, a process that Mia finds both comforting and frustrating. Baking challah together feels like an authentic Jewish experience and an act of creativity; Mia remarks that applying the egg coating is “just like painting.” However, when their rabbi joins the family for Shabbat dinner, the meal becomes a scene of recriminations. Characters’ postures and facial expressions convey underlying tensions and a failure to communicate. Mia pulls a hood over her head, clenches her fists, and finally erupts in anger over her mother’s apparent dishonesty. Family members’ opposing interpretations of the truth are inevitable, but for Mia, they have become impossible to reconcile.

In her author’s note, Cohen relates that her father died when she was nine years old; Mia’s journey to visit him is not based on one she herself undertook. However, it becomes a key part of Mia’s quest. Once Mia arrives in Oklahoma, she begins an intense exploration of the community that she hopes to assimilate into her self-image. There is no facile balance between the Jewish and Muskogee elements of her heritage. Mia learns about a painful past, when Native American children were forcibly educated in schools meant to eradicate their culture. She also glimpses some ambivalence within her father’s family about how to maintain a traditional way of life and avoid distorted interpretations of Indigenous customs.

Since Mia does not live with her father’s family, she responds to their love as an outsider, with gratitude for their welcome. By contrast, her Jewish community bears the burden of daily imperfections. Rabbi Goldfarb veers between inexcusable ignorance and laudable sensitivity. Mia’s stepfather, reaching out in friendship during his meeting with her father, repeats a thoughtless stereotype about the supposed mechanical ineptitude of Jewish men.

Cohen eloquently defends the legitimacy of Native American culture in her author’s note, critiquing the misnomer of “legends” applied to Indigenous creation stories. She states that these sacred writings deserve the same dignity granted to Rabbi Goldfarb’s “Old Testament” (although it should be noted that a rabbi would likely never refer to the Hebrew Bible using that term, which is rooted in the Christian belief that a New Testament has completed and perfected the original one).

Defining one’s identity can be a lifelong task. Emily Bowen Cohen’s new graphic novel is highly recommended and gives voice to one young woman’s deepening awareness of that truth.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.