Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

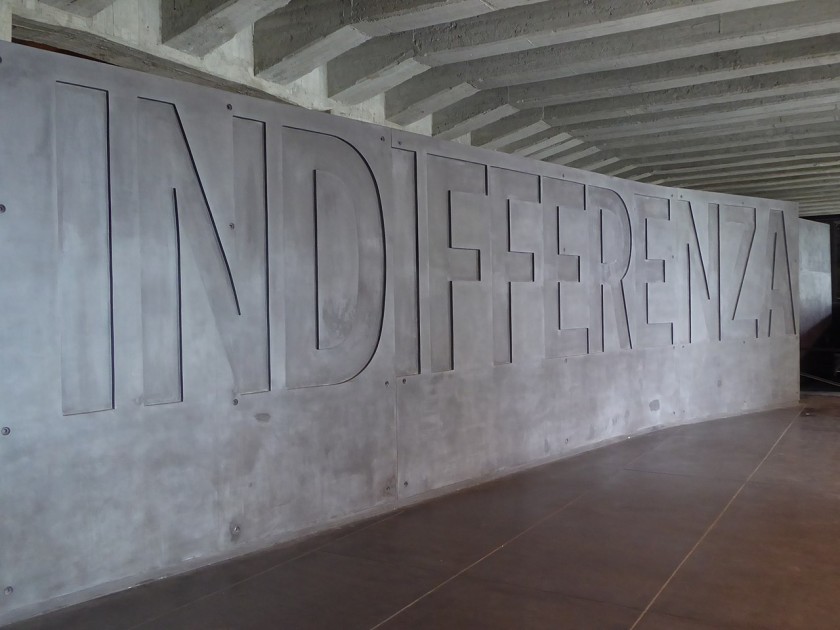

Holocaust Memorial in Milan, Italy, May 2018

Photo by Ardfern via Wikimedia Commons

During Mussolini’s regime there was a huge statue of him on horseback in the Bologna football stadium. On July 25, 1943, the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III removed Mussolini (or Il Duce) from office and had him arrested, and on this same day that statue was given a similar treatment: the head was cut off and gleefully paraded through Bologna’s ancient streets. After World War II ended, and Mussolini had been killed by the Italian Resistance, the rest of the statue was melted down to create two life-size statues of Resistance fighters, a man and a woman, standing defiantly in the Piazza VII November 1944 which commemorates a battle between the partisans and the occupying Germans.

Fifty years later, in Rome, during the trial of Nazi officer Erich Priebke, Neo Fascists hastily erected a makeshift memorial in the Via Rasella. Priebke ordered the murder of 377 Romans in retaliation for a partisan attack on the occupying German army. The makeshift memorial was created where the SS were ambushed. It included an inscription honoring the German dead: “Victims of an antifascist and partisan slaughter perpetrated by vile assassins.”

For almost a century, Italians have been trying to come to terms with their ambiguous past. Twenty years of Fascist rule, and an alliance with Hitler, ended on July 25, 1943, but was followed by a civil war between Italian partisans and the remnants of Mussolini’s forces. That internal conflict was overlaid by the invasion of the peninsula from the south by Allied armies and from the north by the Germans. Even when the fighting supposedly ended on July 28, l945, there was often a violent settling of accounts between Italians.

The result has been a landscape of memory in Italy that includes memorials to both the Resistance and the Fascists. There are additional monuments that recall civilians killed by the Fascists, the Nazis, and the Allied bombings.

Part of that complex and contradictory memoryscape are memorials concerning the Holocaust. However, Jews have had to be careful when making their story a part of the national memory. As one historian has said, “inherent in civil war itself is something that feeds the tendency to bury the memory of it.” If there has been a concerted effort to obscure or hide the disturbing nature of the Italian involvement in World War II, the Holocaust memorials have participated in that effort.

In 1947, Milan’s Jewish Community erected a memorial in the city’s Monumental Cemetery that contained twelve tombstones bearing the names and history of twelve Italian Jews who were killed during World War II. The choice of those twelve Jews was carefully considered. Four died as partisans and one had volunteered to fight for the Allied armies. It is not clear whether the partisans died fighting Germans or Italians. That seems to be intentionally obscured. And most importantly all twelve died on Italian soil. None of the twelve died at Auschwitz, although thousands of Italian Jews were killed there. To specifically mention those victims would be a reminder that Italians informed on their Jewish neighbors, and other Italians loaded the trains and drove them out of Milan, Rome, and elsewhere towards their death.

Jews have had to be careful when making their story a part of the national memory.

The Jews who were transported to Auschwitz are remembered in another Milan memorial. In 1995, a Catholic organization, Sant’Egidio, informed the Jewish community that train Platform 21, where Jews had been deported, still existed as part of the Milan railroad station, although it was not operational. The Archbishop of Milan, Carlo Maria Martini set in motion a plan for a memorial at the site which came to fruition in 2013. The memorial features the platform, which was hidden underground so that the deportations would not be visible to the rest of Milan, original livestock cars, and the elevator that lifted the cars with their human cargo to ground level. There is a long wall of the victims’ names, and as one enters the memorial there is another long wall with monumental letters spelling out one word, INDIFFERENZA, “indifference,” supposedly the human frailty that had made the Holocaust possible.

Certainly, indifference played a role in allowing the murder of Italy’s Jews. But just as certainly there were Italians who intentionally arrested and rounded up Jews, and Italians who drove the trains. Surely, in Milan, there were people like Doctor Luigi Parravicini and Father Paolo Liggeri who saved numerous Jews in their hospitals and churches. Father Liggeri was himself deported to Mauthausen. But there were other Italians who informed on Jews to the local and German authorities. None of these people, neither the heroes nor the villains, were indifferent. However if one is bent on burying the memory of what actually happened even at the entrance to a Holocaust memorial, a lot can be hidden behind the word “Indifferenza.”

After two thousand Jews in Rome had been rounded up and sent to Auschwitz and after 77 Jews had been murdered among the 330 Romans killed by Erich Priebke and his fellow Nazis, Giacomo Debenedetti, a Jewish Professor at the University of Rome, asked for the Jewish fallen that “at a roll call of the dead their names be included among those of other soldiers who have fallen in the war. . Soldier Coen, Soldier Levi, Soldier Abramovic, Soldier Chaim Blumenthal, age five, fell at Leopoli amid his family with his hands tied behind his back while still defending and bearing witness to the cause of liberty.”

That memorial is yet to be built, but with Debenedetti’s roll-call we hear the pain of, not only the Jews who are memorialized in Italy, but all those who died in the War and in the civil war, deaths spent in opposition to tyranny.

Check out Fredric Brandfon’s Intimate Strangers: A History of Jews and Catholics in the City of Rome today!

Fredric Brandfon went to Wesleyan University and received a Doctorate in History of Religions from the University of Pennsylvania. He also has a UCLA law degree. From 1973 – 1988 he was an archaeologist excavating in Israel. After receiving a Mellon Grant to study Philosophy of History, he taught at Central Michigan University, Stockton University, and the College of Charleston.