In the predawn hours of October 16, 1943, Nazi troops gathered at the Portico of Octavia in Rome, barricaded the streets of the Jewish ghetto, and gave the residents twenty minutes to gather their belongings before they would be forcibly removed from their homes. In that same spot almost two thousand years earlier, Roman Emperor Vespasian and his son Titus proclaimed victory over the Judean rebels, launching their triumphant procession through the city and carrying the spoils from the Temple of Jerusalem.

During the intervening two millennia, the Jews of Rome both thrived and endured extreme hardship, their fate alternately buffeted by persecution and acceptance — all at the whims of emperors, governors and popes. They were sometimes protected, sometimes betrayed.

Frederic Brandfon skillfully tackles these stark contradictions in Intimate Strangers: A History of Jews and Catholics in the City of Rome. His book is rich in detail, with comprehensive research drawn from biblical texts and papal decrees, inscriptions from the catacombs, medieval art, and folktales and poetry in Italian, Hebrew, and “ebraico,” the language of the Roman Jews.

Brandfon, a professor of philosophy and religious studies, describes Rome as both “the home of the worldwide Catholic Church, [and] home of the oldest Jewish diaspora community.” He notes that Jews actually predated Catholics in Rome, having lived there since 139 BCE. This pre-Christian history was documented by Josephus, born Yosef ben Matityahu in Jerusalem. He traveled to Rome in 61 CE, attempting unsuccessfully to seek freedom for fellow Jews imprisoned there. He eventually gained favor with Roman officials and chronicled Jewish history in four books intended for the Roman elite.

The treasures captured from Judea and Jerusalem funded the building of the Colosseum. “Accordingly, Jews involuntarily financed the symbol of the Eternal City found today on T‑shirts … in a thousand Roman souvenir shops,” Brandfon wryly observes.

The fate of Roman Jews fluctuated wildly depending on who was pope, as it had depending on who was emperor. As early as 1120, a papal bull accorded Jews certain rights in return for their acceptance of Christian canon law. It decreed that “no Christian shall compel them to come to baptism unwillingly,” nor “seize, imprison, wound, torture, mutilate, kill or inflict violence on them.” Most subsequent popes reaffirmed these orders, and Rome even accepted exiles from the Spanish Inquisition. Still, Jews were considered outsiders and had to be identified as such, lest Christians be “contaminated” by them; certain popes even mandated that Jews wear identifying clothing, like a yellow hat or red coat.

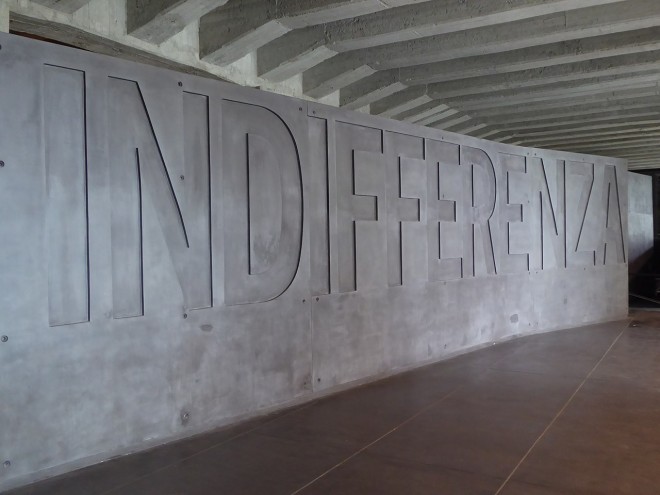

The worst of times began with the establishment of the Jewish ghetto under Pope Paul IV in 1555, who objected to Christians and Jews so much as living on the same street. Jews were confined in a squalid part of the city and allowed only to sell used clothing to make a living. Catholic officials assumed ghetto conditions would be so harsh that Jews would want to convert to Christianity to escape them.

Another effort to convert Jews was mandatory attendance at church sermons. Worried that the Jews would be inattentive, the clergy searched them as they entered the chapel, looking for balls of wax, wool or cotton that could be used as earplugs.

The Risorgimento, a movement that united Italy into one republic, turned the tables once again. While the Vatican refused to recognize the legitimacy of the new nation, Jews, now freed from the ghetto, welcomed it. Rome even had a Jewish mayor, Ernesto Nathan, from 1907 to 1913. But with the rise of Mussolini and the fascists, the pendulum swung back. The Racial Laws, instituted in 1938, barred Jews from most professions, schools, and libraries. Kosher butchers were outlawed.

In 1943, 1,020 Jews were rounded up by the gestapo and shipped to Auschwitz, where all but sixteen perished. Many Roman Jews who eluded the Nazis were given refuge in monasteries, convents, and Catholic schools. Ordinary Catholics hid Jews as well: one family was sheltered for almost a year in the basement of a brothel, while German soldiers were entertained upstairs.

Jews and Catholics became comrades in the resistance, bombing railway stations and bridges and ambushing a column of SS soldiers in 1944, killing thirty-two. In retaliation, the Nazis ordered ten Romans to be murdered for each slain German; they were executed in mines south of the city. That site, the Fosse Ardeatine, has become a national shrine, honoring the Jews and Christians who perished there together for their resistance to fascism, their bones and ashes mixed.

Elaine Elinson is coauthor of the award-winning Wherever There’s a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers, and Poets Shaped Civil Liberties in California.