Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

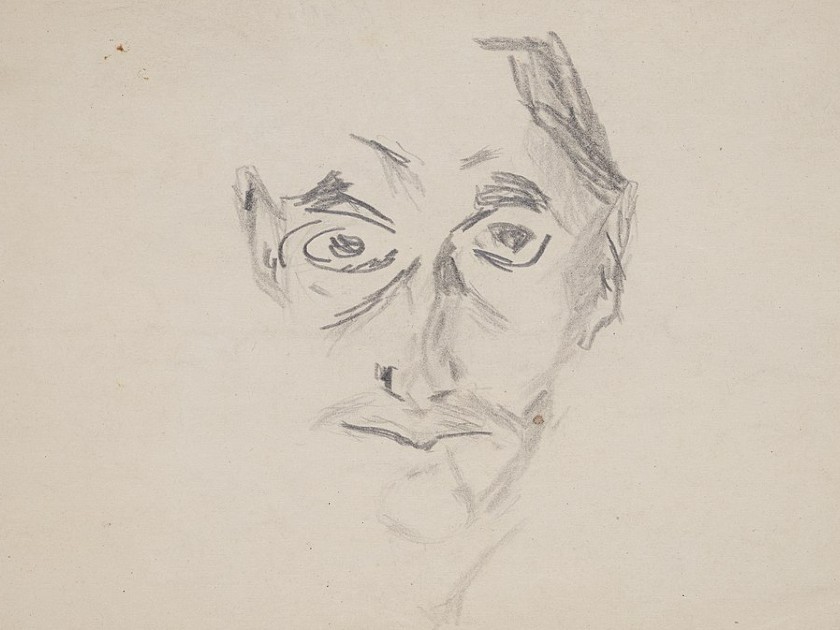

Franz Kafka, self-portrait, 1911

Franz Kafka’s diaries, which he kept between 1909 and 1923, reveal the unsparing self-examination and wide-ranging literary invention of one of the most visionary and influential figures of modern literature. My translation gives English-speaking readers access to the complete, uncensored diaries for the first time. Whereas the sole previous English version, first published in 1948 – 49, was based on a bowdlerized and substantially altered German edition prepared by Kafka’s literary executor, Max Brod, my rendering is based on the original text of Kafka’s handwritten notebooks, as faithfully transcribed in the 1990 German critical edition. Kafka’s unexpurgated, undistorted diaries open a window into his inner life and creative process in all their complexity. Brod’s intrusions diminished that complexity in the service of Kafka’s posthumous sanctification.

A prolific writer and critic, Brod had been Kafka’s closest friend from their university days until Kafka’s untimely death from laryngeal tuberculosis in 1924. Defying his testamentary wishes to burn all the “diaries, manuscripts, letters … sketches, and so on” he left behind, Brod instead applied a heavy editorial hand to this disarray of disparate material, which he brought into print over the next several decades. With his interventions, Brod minimized the fragmentary, unpolished nature of Kafka’s manuscripts and emended the peculiarities and unorthodoxies of his writing. In doing so, Brod was not only fabricating more cohesive, smoothly readable editions, but also fashioning a saintly image of Kafka as a pure literary artist at a remove from the world.

Much of what Brod censored in the diaries was precisely what complicates this picture. Notably, he downplayed the complexity of Kafka’s relationship to sex, camouflaging or sanitizing several passages that recount visits to brothels. In one description of a sex worker, for example, he cut the sentence, “Hair runs thickly from her navel to her private parts,” presumably because he deemed the lewd carnality of the diarist’s gaze unbefitting of the pious Kafka myth. A number of the omitted portions were homoerotic, such as a diary entry Kafka wrote during his stay at a nudist sanatorium: “2 beautiful Swedish boys with long legs, which are so formed and taut that one could really only run one’s tongue along them.”

Brod was not only fabricating more cohesive, smoothly readable editions, but also fashioning a saintly image of Kafka as a pure literary artist at a remove from the world.

Tellingly, Brod was as inclined to tamper with passages implicating Kafka’s Jewishness as he was with those implicating his sexuality. In these areas, at least, it was as if protecting Kafka’s sanctity depended on neutralizing the rigor of his own self-scrutiny. In two successive entries from October 1911, Jewish and sexual matters converged — and Brod managed to fend off the perceived double threat with a single stroke of the pen. In the first of the entries, written on Yom Kippur, Kafka’s observations of his fellow congregants at Prague’s Old New Synagogue during the previous evening’s Kol Nidre service were tinged with mockery of their false piety. To top it all off, he mentioned the presence of “the family of the brothel owner.” In the next entry, he recorded his impressions of that very brothel, which he had frequented a few days earlier: “In the Suha b. [brothel] three days ago.” Simply by deleting the name of the establishment and Kafka’s abbreviated “B.” for Bordell or brothel — since nothing else in the account indicated explicitly what sort of place it was — Brod erased the connection with “the family of the brothel owner” in the preceding entry. As a result, the English translation of Brod’s adaptation even saw fit to replace the definite article with an indefinite: “the family of a brothel owner” (emphasis added). What Kafka actually wrote suggested that, as a recent patron of the brothel, he shared in the impurity he found in the synagogue, that there he (characteristically) recognized himself in his ironic registering of the hypocrisy surrounding him. Brod’s manipulation of the text was typical of his overall approach in its elevation of Kafka to a more distant, uncompromised height.

In contrast to Kafka’s critical appraisal of his fellow Prague Jews, his attitudes toward the members of a traveling Yiddish theater troupe from Lemberg, whom he came to know when they gave a series of guest performances in Prague between 1911 and 1912, were generally positive and open-minded. As reflected in the many diary pages devoted to their performances, of which Kafka attended more than twenty, they inspired his enthusiasm and fascination. He grew enamored of more than one of the actresses, and formed particularly close ties with the actor Jizchak Löwy. In his diaries, he reproduced Löwy’s stories of Jewish life in Warsaw. He also noted his father’s denigration of his friend: “Löwy — My father about him: He who lies down in bed with dogs gets up with bugs.” (It’s unclear whether Kafka’s father or the writer himself is responsible for the unconventional phrasing of the usual idiom about dogs and fleas.)

This comment echoed antipathies that were rife among Prague’s assimilated, German-speaking Jewish bourgeoisie — of which Hermann Kafka was a representative — toward Jews from the East who spoke Yiddish and came from an impoverished shtetl milieu. It’s striking that, in his contempt, Hermann Kafka resorted to the classic antisemitic comparison to animals and insects. Scholars have suggested that such tropes, prevalent as they were in the Austro-Hungarian culture in which Franz Kafka grappled with his own Jewishness, influenced key motifs in his fiction, such as Gregor Samsa waking up as a monstrous insect and Josef K.’s last words at his execution: “Like a dog!

And yet, for all Kafka’s protectiveness of Löwy in the face of his father’s disparagement, in a diary entry about an evening with his friend at the theater, he remarked, “Moreover, L. confessed his gonorrhea to me; then my hair touched his when I leaned toward his head, I grew frightened due to at least the possibility of lice.” Here, Kafka confronted his own Western European Jewish anxiety about the hygiene of his Eastern European Jewish companion. Brod’s excision of these lines exempted Kafka from the reflexive, visceral prejudices that the writer hadn’t shied from acknowledging in himself.

To desanctify Kafka is not simply to bring to light his imperfections, but to give a realer, fuller, richer, and more nuanced sense of who he was, as a human and a writer. In my translation of the restored text of the diaries, I sought to resist any temptation to smooth away rough edges or impose narrow interpretations. My task was, as far as possible, to let the self that Kafka probed so painstakingly in his notebooks speak for itself.

Ross Benjamin’s translations include Friedrich Hölderlin’s Hyperion, Joseph Roth’s Job, and Daniel Kehlmann’s You Should Have Left and Tyll. He was awarded the 2010 Helen and Kurt Wolff Translator’s Prize for his rendering of Michael Maar’s Speak, Nabokov, and he received a Guggenheim fellowship for his work on Franz Kafka’s diaries.