Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

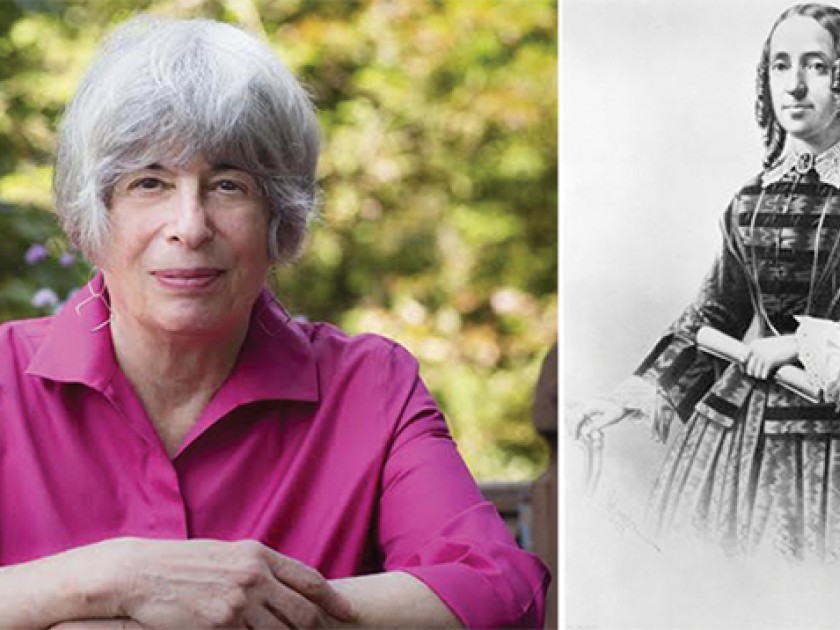

Earlier this week, Bonnie S. Anderson explored the Jewish identity of subject of her book The Rabbi’s Atheist Daughter: Ernestine Rose, International Feminist Pioneer and why she would have been at the front of the Women’s March on Washington this past weekend. Bonnie is guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

The word Judenschmerz, which literally means “Jewish pain,” was coined in the first quarter of the nineteenth century to denote the difficulties of still being identified as Jewish when one has converted from Judaism to Christianity. Often used about the German poet Heinrich Heine, it came to mean suffering from antisemitism when a Jew no longer believes in religion.

Growing up in a nominally Jewish family in New York City of the 1950s, I experienced this pain. My mother had been raised in Ethical Culture, a self-defined “religion centered on ethics rather than theology” with a progressive, largely Jewish membership. My father was an atheist who believed that all religions were a force for evil and all believers stupid. We children were taught nothing about Judaism, never went to temple, and celebrated Christmas and Easter, which my father considered to be “American.” But the greatest family sin was to deny you were Jewish.

In those years, life in New York was segregated along religious lines: there were Jewish buildings, Jewish law firms, Jewish dancing schools. My first experiences of antisemitism occurred at Brearley, an elite private girls’ schools unique for having 25% Jewish students — the others in its cohort were almost exclusively Christian. When I told our headmistress that I wanted to apply to the women’s college at Harvard, she said I wouldn’t get in because “they have a Jewish quota.” I wondered why the head of this prestigious school supported such discrimination. When I interviewed at the women’s college at Brown, I was told that “girls like me” were not very happy there. “What do you mean, ‘girls like me’?” I asked. “Dark girls from New York City,” she replied. Since I was only accepted there, I was nervous about going.

I actually had a fine time. I encountered more antisemitism when I married and changed my maiden name, Sour, to Anderson. Assuming I was not Jewish, a number of my husband’s associates freely voiced antisemitic views, calling my city “Jew York,” saying someone had “jewed them down,” remarking that “all Jews are stingy.” When I wrote my first book with my best friend, Judith Zinsser, who is not Jewish, we used to trick people by asking, “Who’s the Jew?” and then telling them they were wrong.

All this was far milder than the antisemitism Ernestine Rose (1810 – 1892) encountered in the United States. She lost her faith in Judaism at seventeen, became an atheist, and frequently lectured for freethought as well as feminism and anti-slavery. Although she experienced far more prejudice against atheists than Jews, documents reveal at least two instances of antisemitism in her life.

In 1854, Lucy Stone, a co-worker in the women’s rights movement, wrote Rose’s closest female friend, Susan B. Anthony, that since Rose’s “face” was “so essentially Jewish,” and she was “avaricious,” she should not be allowed to represent women’s rights. Although Stone continued this criticism, Anthony paid no attention and continued to place Rose in important roles within the movement.

A more serious instance occurred ten years later, when Horace Seaver, editor of the freethought Boston Investigator newspaper, published a series of antisemitic editorials. Antisemitism directed at the ancient Hebrews had a lengthy tradition within freethought, but Seaver, previously Rose’s friend and champion, now attacked modern Jews, writing that Judaism is “bigoted, narrow, exclusive, and totally unfit for a progressive people like the Americans, among whom we hope it may not spread.”

Ernestine Rose initially answered her friend with humor: “I almost smelt brimstone, genuine Christian brimstone” when I read your piece, “Would you drive them out of Boston… as they were driven out of Spain?” She cited the widely accepted stereotype of “the renowned ‘Yankee,’ who, it is admitted by all, excels the Jew” as a “cunning, sharp trader” and concluded by writing “I know there are honest, honorable Yankees as well as Jews;” you “are one of the very best.”

Seaver responded viciously. “If the Yankees, as a class, like money as well as the Jews,” he replied, “we question whether so many of the former would be found in the ranks of the Union Army. They would be more likely to stay at home to deal in ‘old clothes,’ at a profit of ‘fifteen per shent.’”

This angry correspondence continued for eight weeks. Neither convinced the other. Ernestine Rose stopped writing to the Investigator for almost five years. But she did later resume her friendship with Seaver and expressed great sorrow when he died.

I felt a deep connection with Rose over our similar experiences with Judenschmerz, one of the critical reasons I decided to write her biography. I decided, however, not to put myself in the book, and have never written about this subject before. I hope Rose’s story — and my own — reaches and resonates with readers today, who have encountered religious, racial, or social prejudice in their own lives.

Bonnie S. Anderson taught history and women’s studies at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York for over thirty years. A pioneer in the field of women’s history, Anderson lectures throughout Europe and the United States on women’s movements, international feminism, the history of sexuality, and women’s issues today. The Rabbi’s Atheist Daughter: Ernestine Rose, International Feminist Pioneer is her fourth book.