Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

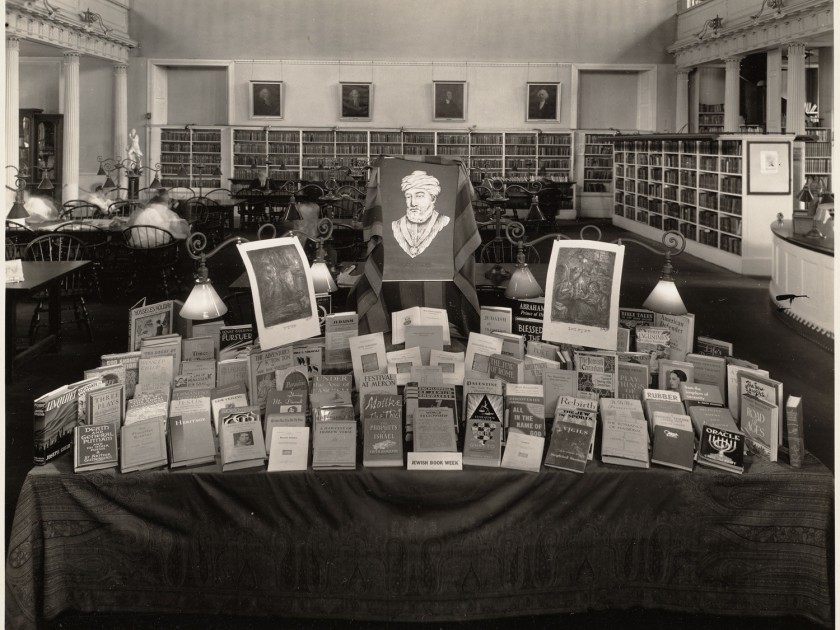

West End Branch. Boston Public Library. Jewish book week. Arranged by Fanny Goldstein, the centerpiece is a wood-carving with gold inlay of Maimonides by the Boston artist Boris Mirski

I am enclosing you a biographic summary plus some publicity connected with Jewish Book Week, of which idea I am the originator in America. Hence, my claim with all due modesty, to some knowledge of the Jewish book.

-Fanny Goldstein to Sarita Olan, May 13, 1935

The history of Jewish Book Week and Jewish Book Month begins with Fanny Goldstein. Born in Kamenets-Podolsk, Russia in 1895, Goldstein immigrated with her family to Boston’s North End in 1900 [2]. Thirteen years later, she began work as an assistant in the North End Branch of the Boston Public Library (BPL) and only six years later, was appointed librarian of the BPL’s Tyler Street Reading Room. The Tyler Street neighborhood was, in Goldstein’s words, “a section of the city that is always foreign.” Goldstein continued to serve immigrant communities throughout her life, striving to provide “a broad and sympathetic program without prejudice, a square deal and a warm welcome to all.” [3] By all accounts, she succeeded. One of the many groups receiving Goldstein’s outreach and support was the Syrian community, which gave her “an exquisitely embroidered Madeira dining-table set,” with a note expressing their “grateful appreciation” for her service, when she left Tyler Street to serve the West End, another of Boston’s immigrant communities [4].

Goldstein was appointed librarian of the West End Branch — the Boston Public Library’s largest neighborhood branch — in 1922 and remained there for thirty-five years until her retirement in 1957. It may have been an act of divine providence that brought Goldstein to the West End Branch, to serve as the building’s last librarian in what were to become the final decades of the old West End. The library had been in the Old West Church since 1896, and Goldstein was greatly inspired and humbled by this fact. She reveled in the building’s history as “a great church, with great pastors,” one that had influenced Boston for over one hundred and fifty years [5]. What had served long ago as the minister’s study became Goldstein’s office, fitting for a woman who approached her life’s work as something akin to a religious calling. Connecting the work of the ministers with the Hebrew Prophets, she was able to embrace the building’s provenance as a Christian house of worship. In a 1942 article on the history of Jewish Book Week published in the Jewish Advocate, Goldstein wrote: “All the preachers of the church had been united in one theme: The Brotherhood of Man. The gospel and the power of the spoken word, as revealed through the Bible, was fearlessly preached. In this work, they relied on the traditions of the Puritan Fathers who in Colonial times staunchly upheld the teachings of the Hebrew Law and Prophets.” [6]

The West End was a densely populated section of the city, with tenements, rooming houses, and factory buildings. As was typical of areas with immigrant and poor populations, the neighborhood also contained settlement houses — the Elizabeth Peabody House, which was known nationally; the West End House, founded by Jewish immigrants; and the Heath Christian Center — where residents could access social services including recreational programs and educational opportunities. The settlement houses were open to all, regardless of religion or ethnic origin [7].

Goldstein formed relationships with the settlement houses and other local institutions. Like other librarians of the BPL, she saw herself as a community leader, performing services for immigrants alongside social workers and public health workers [8]. Many public libraries around the country provided similar outreach to America’s recent arrivals. Boston, however, had an especially rich history upon which to draw. In 1854, the city established the first free large municipal library in the U.S., primarily due to the Boston elite’s desire to provide moral uplift to new immigrants [9].

Serving succeeding populations of new Americans, Massachusetts public libraries continued to set the standard in providing services to immigrants through funds, programs, and personnel dedicated to such needs. They helped immigrants to learn English by providing books in easy form for adult beginners; to become Americanized by providing books about the U.S.; and to preserve their cultures by providing books in their native languages [10]. Goldstein believed that it was important for immigrant groups to maintain a strong sense of cultural pride and identity. Although she had a particular interest in Jewish culture and literature, she was committed to celebrating the cultures of all the library’s constituencies and served on the American Library Association’s Committee on Work with the Foreign Born.

When Goldstein assumed charge of the West End Branch in 1922, “she was impressed with the high intellectual plane” of the Jewish readers but lamented their ignorance of Jewish history and literature and their lack of interest in the library’s many books on Jewish subjects and by Jewish authors [11]. She was determined to promote the library’s collection of Jewish books and create interest in them among the library’s users.

In December 1925, Goldstein put together a display of Jewish books shortly before Hanukkah. It was a simple act. Yet Goldstein was the first person known to arrange such a display at a public library anywhere in the U.S. One year after the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act aimed at curbing immigration of Eastern European Jews and others considered undesirable, and amid the nation’s rising antagonism toward foreigners, Goldstein assembled a display aimed in part at increasing immigrants’ pride in their history and culture.

An editorial in the Jewish Advocate praised Goldstein’s undertaking: “Due to the care and efforts of Miss Fanny Goldstein, the chief librarian of the West End Public Library and the only Jewish librarian in Massachusetts, a unique enterprise was undertaken at this branch library. Miss Goldstein arranged for a Chanukah display of the best English books dealing with the Jewish people.” [12] The paper continued to promote Jewish Book Week with articles and editorials throughout Goldstein’s career, and to decry Jews’ lack of interest in their own literature. The mainstream press also promoted Jewish Book Week. In 1926, the Boston Daily Globe, noting that the West End branch of the BPL served “a large Jewish clientele,” reported that the library’s display included a Hanukkah menorah and signs in English and Yiddish suggesting that books be given as Hanukkah gifts [13].

While Goldstein was popularizing Jewish literature, in Germany that same literature was receiving a different kind of attention. In March 1933, Hitler appeared on the cover of Time. Two months later, university students throughout Germany burned books that Nazi leaders deemed incompatible with German culture. The German Student Corporation, the only organization of German undergraduates sanctioned by Hitler, issued a manifesto in April 1933 giving notice of the book burnings. Students were instructed to search their personal libraries for books by Jewish authors that “through thoughtlessness” may have come into their possession. All such books were to be burned, along with all books by Jewish authors that were held by public libraries.

As German libraries burned Jewish books, Goldstein persisted in celebrating them. But now she turned her attention to fighting antisemitism as well. She was committed to educating the public about the rising antisemitism in Germany and sought to raise awareness beyond the Jewish community. Just three days after the May 10th book burnings, Goldstein published “Autos-da-fe for the Jew and His Book” in the Boston Globe, in which she decried civilization’s decline: “One shudders at the thought of the precious libraries of the land being emptied of their treasures. Libraries. The repositories of civilization and keepers of the precious records and manuscripts. And there are so many in Germany….” [14].

The following year, Goldstein urged the celebration of Jewish Book Week as a tonic for world events. “Libraries can be dispensers of peace through emphasizing the gospel of the book as an aid to good will and universal brotherhood.” [15] She continued to frame Jewish Book Week as an antidote to antisemitism throughout the period of World War II. In her Jewish Book Week radio broadcast in 1940, Goldstein asserted that even book burnings could not extinguish the “indomitable faith and idealism” of the Jews, and told her listeners that the weeklong celebration was “a healing balm for our bleeding wounds caused by bigotry, intolerance, and anti-Semitism.” Ever the pacifist, Goldstein declared that the observance of Jewish Book Week “does not call for swords or bayonets; gases or bombs. It is a dignified, majestic emphasis on our heritage, and a rededication to the sanctity of our homes through literature.” [16]

That same year, in a message written as Chairman of the National Committee for Jewish Book Week and distributed as part of her Suggestive Material for the Observance of Jewish Book Week, Goldstein asserted:

The National Committee for Jewish Book Week feels that in times such as the present, when books are being burned in other parts of the world, it is the greatest good fortune to be part of America. In this democratic country, our books are not destroyed, but scholarship and publishing are encouraged for all who would read and understand. It is therefore not only a duty and a privilege, but a matter of pride as well, that we, the PEOPLE OF THE BOOK, sponsor and support a National Jewish Book Week in every city and hamlet. [17]

Cities and hamlets heeded Goldstein’s call. From 1936 to 1959, Jewish Book Week and Jewish Book Month were celebrated in many communities across the nation. Goldstein was tireless in her promotion of Jewish Book Week, imploring librarians across the U.S. to place “special emphasis during this period on the gospel of the Jewish book” and writing articles for the Jewish Advocate and Boston’s dailies [18].

The Jewish Publication Society’s first Spring Book Festival, in 1936, was timed to coincide with Jewish Book Week. The Society sold 4,000 books at the festival, which became an annual event. As Jewish Book Week was moved to the Hanukkah season in later years, so was the festival [19]. Even the State Department’s “Voice of America” radio station participated in the celebration of Jewish literature, beaming a talk on Jewish Book Month to Israel in 1951. The speaker, Dr. Azriel Eisenberg of New York’s Jewish Education Committee Department, delivered the address in Hebrew [20].

Goldstein met regularly in New York City with other members of the National Committee for Jewish Book Week, a distinguished group of scholars and community leaders. She was the only woman in the room and the only person without even a college degree. Yet, Fanny Goldstein had provided the impetus for the cause around which they had gathered [21].

While Goldstein was not intimidated by male rabbis and scholars, she was disillusioned with the arrogance and overbearingness of some. In addition to confronting sexist attitudes, Goldstein encountered outright exclusion as well. Goldstein’s measured view of scholars and rabbis was partly due to her genuine respect and concern for all people regardless of their station in life. As her friend Rabbi Benjamin Grossman noted after her passing, Goldstein “had a feeling for the lost soul.” [22] She reached out to the marginalized and disenfranchised, including homeless individuals and prisoners. She made many visits to the Charlestown State Prison, attended plays staged by prisoners, accompanied Rabbi Grossman on holiday visits, sent books to prisoners, and encouraged their literary pursuits. In September 1948 she wrote to Charlestown’s new warden, asking that he allow her to continue to send boxes of sugar to the Jewish prisoners during the holiday of Rosh Hashanah. There were twelve Jewish inmates that year to whom she wished to send her “little gift,” and one James Kerrigan with whom she had “considerable correspondence on books and the poetry which he has been writing.” [23] She held annual Christmas Eve Open Houses at the library, welcoming those whom others might have turned away, serving turkey sandwiches, doughnuts, and coffee to many who would otherwise go hungry.

Fanny Goldstein touched the lives of many — immigrant and Boston native; Jew and Christian; the well-to-do and the destitute; the prisoner and the scholar; of all creeds and from all corners of the world. She was committed to social justice, equal treatment for all, and a just and peaceful world. Her work promoting Jewish books continues to bear fruit today, beyond anything she could have imagined.

[1](This refers to the title.) I thank the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives for its financial support of the research undertaken for my dissertation, “With All Due Modesty: The Selected Letters of Fanny Goldstein” (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Boston University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 2018, https://hdl.handle.net/2144/33238, from which this essay is taken.

[2] Some sources give Goldstein’s year of birth as 1888. See, for example, Joy Kingsolver, “Goldstein, Fanny,” American National Biography Online, http://www.anb.org/articles/09/09 – 00897.html.

[3] Fanny Goldstein, “Tyler Street Reading Room,” Annual Report of the Library Department for the Year 1920 – 1921 (Boston: Feb. 21, 1921), 77.

[4] Literary Life: Staff Bulletin of the Boston Public Library, Jan. 15, 1923.

[5] Fanny Goldstein, “The Story of Jewish Book Week; Its History and Influence,” Jewish Advocate, June 12, 1942.

[6] Ibid.

[7] See Sean M. Fisher and Carolyn Hughes, eds., The Last Tenement: Confronting Community and Urban Renewal in Boston’s West End (Boston: The Bostonian Society, 1992), 15.

[8] See Plummer Alston Jones, Jr., Libraries, Immigrants, and the American Experience (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999), 10.

[9] See Wayne A. Wiegand, Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library (New York: Oxford University Press), 25.

[10] See Jones, 169.

[11] Goldstein, “The Story of Jewish Book Week.”

[12] “Chanukah Display at West End Public Library,” Jewish Advocate, December 17, 1925.

[13] “Chanukah Book Display at Library,” Boston Daily Globe, December 4, 1926.

[14] Fanny Goldstein, “Autos-da-fe for the Jew and His Book,” Boston Globe, May 13, 1933.

[15] Fanny Goldstein, “Jewish Book Week” (letter to the editor), Bulletin of the American Library Association 28, no. 4 (April 1934): 221.

[16] Fanny Goldstein, “Why a Jewish Book Week” (radio broadcast), Boston, Mass., 20 Dec. 1940.

[17] Fanny Goldstein, “Jewish Book Week Message,” in Suggestive Material for the Observance of Jewish Book Week, December 22 – 29, 1940, compiled by Fanny Goldstein.

[18] Fanny Goldstein, “Jewish Book Week” (letter to the editor), Bulletin of the American Library Association 26, no. 5 (May 1932): 347.

[19] See Jonathan R. Sarna, JPS: The Americanization of Jewish Culture, 1888 – 1988 (New York: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 181.

[20] “Jewish Book Month Observance Begins,” Philadelphia Jewish Exponent, 23 Nov. 1951.

[21] Silvia Glick, “Judaica’s First Lady: Fanny Goldstein and Jewish Book Week” (unpublished manuscript, May 4, 2011).

[22] “Throngs at Goldstein Rites: ‘Noble of Character,’ Says Rabbi,” Boston Globe, Dec. 28, 1961.

[23] Goldstein to Warden E. L. Spurr, 29 Sept. 1948.

Silvia P. Glick is a writer and editor. She lives in Somerville, Massachusetts.