Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

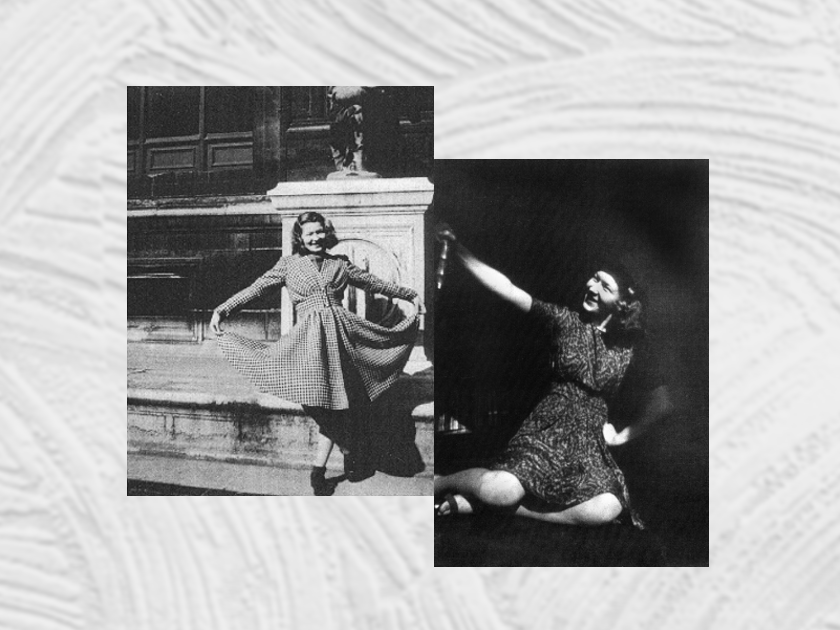

Left: Annette Zazou. Albert Harlingue/Sonia Mosse © Gaston Paris — Roger-Viollet.

Right: Annette in the courtyard of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Credited to Salvatore Baccarice

All images courtesy of the authors

“Here is Annette Zelman, just nineteen … Her mane of thick, dark blond hair gleams in the sunlight, pinned in a fashion all her own. Curls akimbo. A headband hauls them back off her face, almost. She is still a teenager; the baby fat has not yet fallen from the cheeks of her face. Her eyes squint in the winter light and crinkle in a full-on smile.” Here is a lost girl of the Holocaust.

Annette wasn’t always lost. She was the sun around which her family revolved. The leader of the children. First mate of the Zelman Circus, as her family was lovingly called. The Zelman apartment had a revolving door policy; no one knocked. When masses of children (Zelmans, as well as neighbors) weren’t running in and out on roller skates or blowing the harmonica, Madame Singer was gracing the apartment “with a new corkscrew hairstyle to accompany the watery grand symphony of a friendly little cry,” and Madame Bessarabie was sleeping on a pallet under the dinner table. The only way nineteen-year-old Annette could find any time or space for herself was at the famed Café de Flore, where she spent afternoons bonding with other young students, intellectuals, and artists.

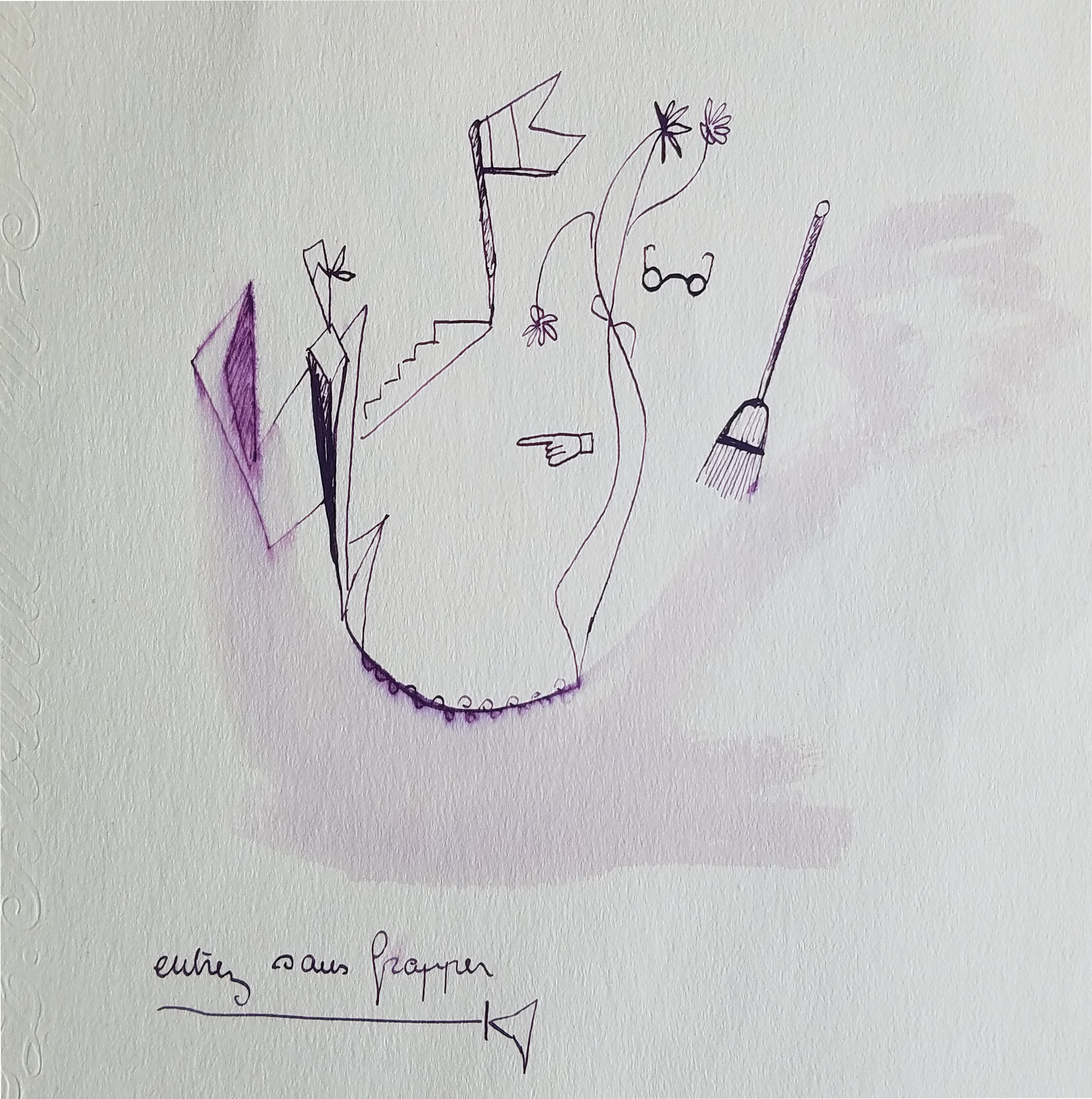

In the 1940s, Annette studied at the prestigious Academie des Beaux Arts, France’s premier art school, and the Café de Flore was just a stone’s throw away. On any given afternoon, one could find writers like Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre, and painters like Picasso and Solange trying to keep warm by the cafe’s coal stove. It was the surrealists to whom Annette felt most connected, and she gravitated to their humor, whimsy, and abstract perceptions. She moved from learning classical art to experimenting with surrealist and automatic writing. An autodidact, she tended toward anything new, strange, and experimental. She and her friends rebelled against the occupation by frequenting the jazz clubs and dance parties that the Nazis were trying to shut down. Among her crowd were intellectual women and men — philosophers, writers, musicians, and artists. She fell in love with a couple of them, but it was Jean Jausion, the surrealist poet, who captured her heart. As the noose around Parisian Jews tightened, the Zelman family prepared to flee for the Free Zone, the part of France that was governed by the Vichy government rather than Nazi-occupying forces. Laws were different for Jews in the Free Zone, so it was safer there. Annette told her family she would close up the family apartment and follow in a few days. Instead, she moved in with her lover.

Entriez sans Frapperor (Enter without knocking), Gouache and ink, 1941, by Annette Zelman

Jean and Annette believed that by getting married, they would protect her from Nazi authorities. She would replace the Zelman name and become Mrs. Jean Jausion, daughter-in-law to a famous Parisian doctor, and friend of antisemite and collaborationist Jean Cocteau. She was in the family apartment when there was an ominous knock on the door. Minutes later, Annette was in a paddy wagon with the “Turfs,” or streetwalkers. She was carted through the night to Le Citadel, the Palais de Justice: the monstrous limestone fortress made famous in Les Misérables.

Here was Boubi, an Algerian redhead arrested in her evening gown for making a phone call. Here was Tamara Isserlis, a medical student who didn’t get in the Jewish car at the back of the metro. Here were Elise Mela and her mother, arrested for going to the mayor’s office to pick up their yellow stars without wearing them on the way. And here was Annette Zelman, guilty of trying to marry a non-Jew. Her crime was love.

The tragedy of being a lost girl of the Holocaust, whether she voluntarily submitted to government service, as the young women of the first official Jewish transport to Auschwitz did, or whether she was arrested for petty crimes, is that she was completely innocent. She acted like any teenager or young adult would, trying to have fun despite the war and believing herself immortal.

There are so many young women lost to history. Names on lists without faces or stories, until someone comes along and opens up a random box in an archive, reads a footnote in a memoir, or finds an obscure account that mentions those names. Maybe Yad Vashem has a photo. Or, if not Yad Vashem, maybe Memorial de la Shoah, or the Państwowe Muzeum at Auschwitz-Birkenau, or the United States Memorial Holocaust Museum, or the Service historique de la Défense in Caen, France. Maybe. Too often there is no family member searching for a lost girl because there is no family left – they are a lost family. But occasionally, someone is out there, looking.

For example, Elise Mela — who joined Annette in the first transport of French Jewish women — had a surviving cousin who asked if anyone had information on what happened to his aunt and her daughter. His plea is dated 1978, thirty-six years after they disappeared. And only now can we answer his query. She arrived at Auschwitz on June 22 and died on the same day as her mother, probably as part of a selection. Arrested together. Died together. War is a family disease.

On the fiftieth anniversary of Annette Zelman’s marriage announcement, Annette’s little brother, Cami, hadn’t forgotten her. He asked the Contemporary Jewish Documentation Centre, “Why weren’t the people who denounced Annette tried in a court of law and ruined?”

It has taken eighty years for Annette’s only still living sibling, her little sister Michele, to know the truth. At ninety-four years old, Michele finally knows that Annette was last seen caring for two ill friends at Auschwitz-Birkenau. She knows that Annette was alive for at least eight weeks after she and her friends arrived in camp. She knows that Annette’s story, letters, and her art are forever recorded, so that she and the other women of her transport can be remembered. And she knows that Annette’s last known words are no longer lost to history: “Merci. Thank you.”

Star Crossed: A True WWII Romeo and Juliet Love Story in Hitler’s Paris by Heather Dune Macadam and Simon Worrall

Heather Dune Macadam is the author of the international bestseller and Pen Award Finalist 999: The Extraordinary Young Women of the First Official Transport to Auschwitz, translated into 18 languages, and the producer/director of its companion documentary film, 999. Her first book was the bestselling memoir Rena’s Promise: A Story of Sisters in Auschwitz. A New York State Council of the Arts Fellow and recipient of a Society of Authors Research Grant, she is a board member of Cities of Peace: Auschwitz and the director and president of the Rena’s Promise Foundation. Her work in the battle against Holocaust denial has been recognized by Yad Vashem in the UK and Israel, the USC Shoah Foundation, the National Museum of Jewish History in Bratislava, Slovakia, and the Panstowe Museum of Auschwitz in Oswiecim, Poland. She and her partner, Simon Worrall, divide their time between East Hampton, New York, and Herefordshire, England.

Simon Worrall is the author of two highly acclaimed books, The Poet and the Murderer (Dutton & Plume/Penguin Putnam USA, 2002; Fourth Estate UK), which William Styron called, “A gripping tale, done with great style and elegance…it held me in its spell from beginning to end,” and the novelized true story of his mother in World War II, The Very White of Love (HarperCollins, 2018). A Francophile since his Parisian childhood, Simon is fluent in French and speaks five other languages. He was the curator and interviewer for National Geographic’s “Book Talk” program for many years. He has been published in The Independent, The Guardian, The London Times, Marie Claire, GQ, and numerous other publications worldwide. His feature, “Emily Dickinson Goes To Las Vegas,” was the first piece of nonfiction ever published by George Plimpton in The Paris Review. Worrall is an experienced broadcaster, whose commentaries have aired on the BBC and NPR.