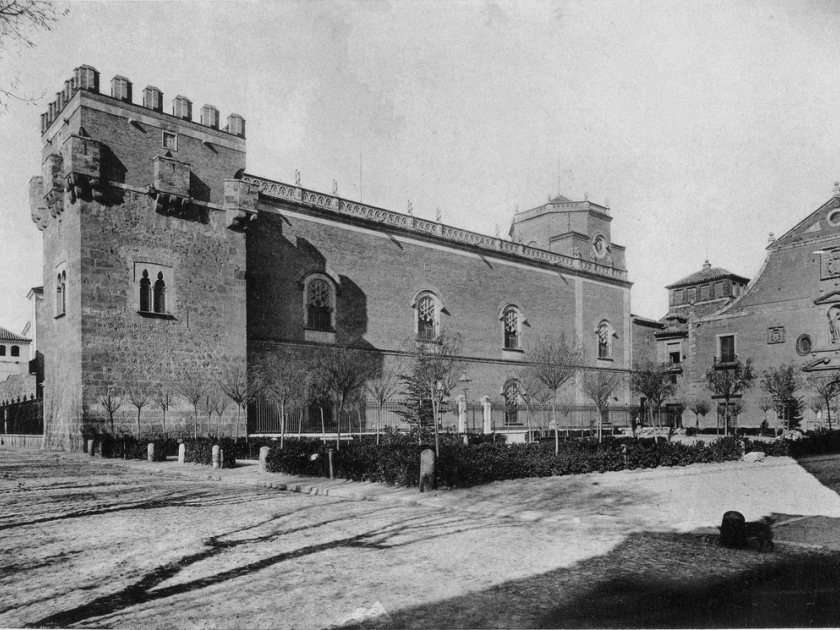

Archbishop’s Palace in Alcalá de Henares, Spain (Hauser y Menet, 1892)

In the wacky world of late medieval Spain — where gambling was a major crime — conversion to Christianity could be a get-out-of-jail-free card. A newly converted gambler didn’t have to pay his debts of honor if his creditors were Jewish, because a Jew couldn’t go after a Christian and the Church authorities, pleased at gaining a new soul, would ignore a first offense.

When I began researching A Ceiling Made of Eggshells, my novel for kids ten and up about the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, I knew little more than that there had been an expulsion and that my ancestors on my father’s side had been among the expelled. As I read the history, I felt that I had entered a dreamscape, where ordinary understanding was no longer applied.

Some discoveries charmed me: an authority on Jewish law laid out the circumstances when it was acceptable to break the Sabbath to prepare an amulet for a sick person; among a list of occupations carried out by Jews, I found lion-tamers!

As I read the history, I felt that I had entered a dreamscape, where ordinary understanding was no longer applied.

Other discoveries were just odd: at one time, shoes worn by Jews older than fifteen were taxed semi-annually. (Footwear was made to last back then; the same pair of shoes may have been taxed many times and paid eventually by an heir.)

Another discovery gobsmacked me: priests and monks invaded synagogues at will during services to harangue the congregation about eternal hellfire. The only constraint on the clerics was occasional legislation limiting their numbers in the synagogues.

But one discovery was particularly troubling. I had to read this fact more than once from more than one source to understand it: in the Middle Ages, in all the kingdoms that would become modern Spain, Jews were the property — literally — of the monarchs. This was an odd sort of slavery because Jews could move about and choose their own occupations, but if a Jew was injured or died, compensation went to the monarch who was considered to have taken the loss.

Sometimes this bondage worked to the advantage of the Jewish population, especially during periods when Jews were prosperous, because the royals protected their assets. But when ordinary Christians were angry with the king, they attacked his possessions — his castles and his Jews.

Disturbingly familiar was the badge — sometimes yellow, sometimes red — that Jews had to wear; unfamiliar was the fact that rich Jews could buy their way out of the requirement.

Disturbingly familiar was the badge — sometimes yellow, sometimes red — that Jews had to wear.

The Inquisition was instituted kingdom-wide in 1480, and mostly persecuted conversos, converts to Christianity, who were suspected of Judaizing, or continuing their former worship since the conversion was often forced. The possessions of the accused were impounded, and, if there was a conviction, shared between the Church and the monarchs. The Inquisition was lucrative!

Practicing Jews were drawn into the Inquisition’s net, too, pressed to inform on conversos, who might be family members, friends, business partners, or clients. A Jewish butcher’s Christian customers, for instance, would certainly be Judaizers, or they wouldn’t want kosher meat.

If a Jew were convicted of denouncing someone falsely, he or she would be relaxed, as it was called, or turned over into the hands of the secular authorities for execution.

The blood-libel trial known as the Holy Child of La Guardia is an example of bizarre Spanish Inquisition jurisprudence. A converso was led gradually by torture and terror to confessing — along with a few other converts and several practicing Jews — to murdering a Christian boy and using his heart and a communion wafer in a magic rite to destroy the Christians of Spain by giving them rabies. But, since the accused were all questioned separately, their confessions varied, and each gave a different location for the body. The most down-the-rabbit-hole aspect of this is that no search was made for a body, and no child was ever declared missing. But on November 14, 1491, executions were carried out in an auto-de-fé, and riots took place across Spain following this bloody judgment.

My marginalia in my books reveal my surprise again and again: ! that the Crown exacted a departure fee from the fleeing Jews — who were not permitted to stay (unless they converted); whoa! that the Crown collected several years’ advance income tax from the departing Jews, so that the kingdom wouldn’t suffer for the loss of their industry; ai! that a ship’s captain took payment from Jews to transport them to North Africa and then sold them to pirates who would capture them on the high seas and in turn sell them into slavery — not the royal kind.

This was a stranger world than any I had created in my fantasies for children, which include exotic creatures like dragons and ogres. How much of this world would I manage to reflect? What had it been like to live when most people, not just Jews, had vanishingly little agency? How did they regard themselves and their lives?

What had it been like to live when most people, not just Jews, had vanishingly little agency? How did they regard themselves and their lives?

I wanted my main character to be a girl, though a girl would have less power than anyone. How would she be able to move my story along?

There still were a few Jewish financiers and courtiers left in the fifteenth century, among them the philosopher Isaac Abravanel. I read a biography of him, plotted his travels across Spain, and his involvement in the great events of the day. Then I developed a very loose version of him, Don Joseph Cantala, and made him the grandfather of my protagonist, Loma. When Don Joseph’s wife dies of plague and Loma survives against all expectations, he becomes attached to her. Out of loneliness, he brings her along with him on the missions undertaken by the real Abravanel.

Earlier, when Loma is struck with the plague and before her grandmother becomes ill, her grandmother ties her amulet around Loma’s neck to protect her from the evil eye — introducing medieval superstition. Tragically, Loma believes for years that she caused her grandmother’s death because she had the amulet.

As a child, Loma is shy and afraid of discord. Her grandmother keeps her out of the synagogue until the clerics have left, but after her death, no one else thinks of this. When a terrified Loma shrieks, a priest lifts her up and parades her about as an example of proper fear of hellfire.

To endow her with agency, I gave poor Don Joseph occasional spells — minor strokes in modern terms — when Loma has no choice but to act. But because I didn’t want her to be a twenty-first century child in period costume, she credits God or her dead grandmother for every smart action she takes. And I allowed her no other ambition than to be a wife and mother. The life she has isn’t the life she seeks.

But because I didn’t want her to be a twenty-first century child in period costume, she credits God or her dead grandmother for every smart action she takes.

The badge enters the story through its absence when Loma is briefly kidnapped by a couple who plan to baptize her and adopt her. The lack of a badge, though she’s clearly a Jew, convinces her captors that she comes from a prominent family and there will be consequences if they keep her.

Loma’s older brother, a compulsive gambler, does convert to avoid the consequences of a bad luck streak. When one of his unpaid Jewish creditors is accused by inquisitors of taking part in the La Guardia blood libel plot, he takes revenge by naming the brother as a co-conspirator.

That the Jews belong to Ferdinand and Isabella is one of the arguments advanced by Don Joseph when he tries to persuade the monarchs not to go through with the expulsion. He points out that, unlike other subjects who also owe allegiance to a bishop or a noble, the Jews’ loyalty is undivided.

I loved the research and the writing. A Ceiling Made of Eggshells became a tapestry for me, as I wove in the threads of history. But I failed to include even one lion tamer!

Gail Carson Levine has published twenty-five books for children. She is best known for her Newbery Honor book Ella Enchanted. Her other Jewish-themed historical novel, Dave at Night, is loosely based on her father’s childhood in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. Most of her books are fantasy novels, but she has two picture books and two how-to’s about writing, also for children.