Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

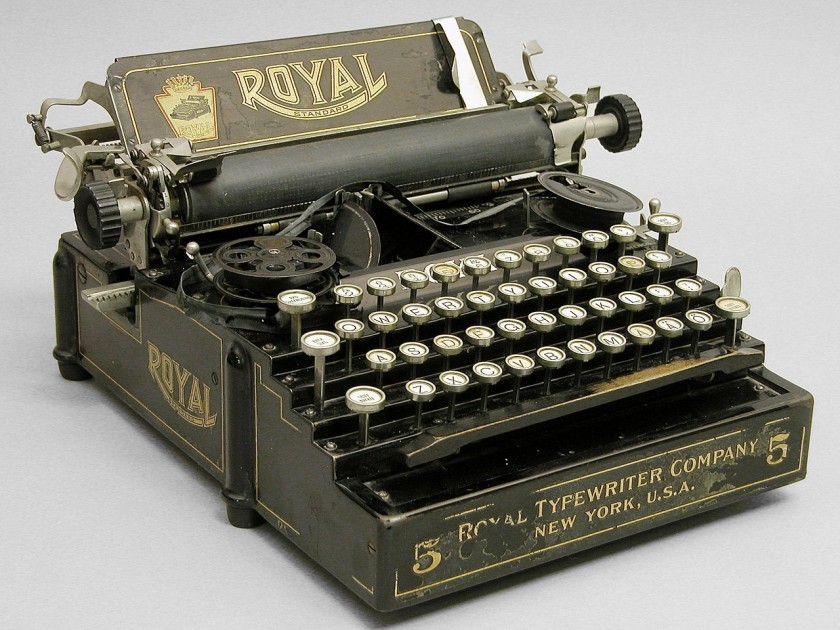

Image from the Blekinge museum

“For six hours every day Isabel and Rosa sat next to each other at a stainless steel work table in the kibbutz kitchen peeling, dicing, and mixing vegetables for a thousand people’s breakfasts, lunches, and dinners. Isabel’s timid questions drew out the war and camp tales curled inside Rosa for decades. Rosa’s responses emerged first in small ripples then in large knock down waves that overwhelmed them. Some days Rosa left the kitchen early crushed by the load of sense memories. After a few months Isabel asked Rosa if she could write her story down. In English.”

Thus Isabel Toledo becomes a ghostwriter for Holocaust survivors, in Make it Concrete (2019) my novel about an American woman living in Israel who stumbles into her profession.

When the book opens Isabel is penning her sixteenth book in twenty years, and it’s taking its toll on her. The boundaries between past atrocities and current realities are no longer so firm. She is less resilient when it comes to her own children’s safety, particularly her daughter who is a soldier in a combat unit. Isabel feels on the verge of collapse even as the gravity of her work pushes her to continue.

Isabel knows well the insider/outsider dilemma of the immigrant. As much as she is a part of Israeli society, she lives with “mistranslations on all sides.” To make matters worse, she doesn’t share a mother tongue either with her mother (Polish, Yiddish) or with her children (Hebrew). She is simultaneously alienated and enriched by this. No one except her close friend Molly, a Jew from Dublin — Yiddish with an Irish accent — understands the full the depth of her belonging and yet not belonging.

Thus Isabel Toledo becomes a ghostwriter for Holocaust survivors.

Many years ago, a colleague of mine, Axel Stähler, invited me to a conference on post-colonial literature in Münster, Germany. He had managed to convince the conference organizers that Jews fit the criteria of a colonized people, though not in one land, nor over one specific period of time — a unique version of colonialism in which they were subject to foreign rule and suffered oppression similar to many colonized populations, even if they were not technically ‘native.’ Not everyone at the conference agreed with this categorization, though in recent years there has been a softening towards it in literary studies, especially with the growth of terms like diaspora, migration, and marginalization at home. Characters such as Dickens’s Fagin, and Shakespeare’s Shylock can now be easily analyzed under the rubric of a post-colonial Jewish history and culture (and not just an overarching antisemitism).

At the conference I read a short story entitled “Silhouette,” about an American woman who flees New York City and its violence for the bucolic tranquility of a kibbutz in the Western Galilee. Only violence follows her there as well. Amidst the banana groves and agricultural fields, the community comes under rocket attack from Hezbollah in Lebanon. And then a homeless dog is attacked both by a dog and children who ‘belong.’ The protagonist is appalled by this violence and identifies with the outcast dog. ‘Who isn’t a stray?’ she asks. The tension of being an insider/outsider, of being a ‘stray,’ is one of the ideas I return to over and over again in my fiction, and most recently in Make it Concrete.

Over coffee, suddenly, Axel asked me if I were an Israeli or American writer. I was stunned, unsure how to even begin to answer this question that no one had ever asked me — and that I had never asked myself. Axel theorized that for a Jewish writer to live in Israel and write in English — not Hebrew — was an expression of post-colonialism. Like Indians who write in English and not Bengali, or African or Caribbean writers who likewise write in English when they could be writing from home in their country’s native tongue.

Over coffee, suddenly, Axel asked me if I were an Israeli or American writer. I was stunned, unsure how to even begin to answer this question that no one had ever asked me — and that I had never asked myself.

I asked Axel why I had to choose, why couldn’t I be both, a hybrid — an American writer who writes about Israel, and an Israeli writer who writes in English. As a child of immigrants who themselves were children of immigrant refugees, I was comfortable with hybridity and resisted a simplistic binary. For months, Axel’s question haunted me. If I were an Israeli writer, shouldn’t I write in Hebrew? And what about how different I feel from Israeli society sometimes? And what about my limited Hebrew that follows me like a shadow, limned in guilt? Hebrew is part of the children of Israel’s project of Return. It’s the Holy Language, morphed once again into the quotidian, a kind of ‘normalization’ within the nation.

With discomfort I asked myself if I could convey with all its complexity and nuance, what goes on in today’s Israel if I continued to write about it in English?

Isabel Toledo, the protagonist of Make it Concrete, also lives out this quandary though a little differently. Like me, she lives to some extent in Hebrew, but writes in English, because she knows herself as a writer in English — yet she is writing about Europe. These stories of the Jews of Europe that she makes concrete end up being realized in Israel. How can I allow myself to limp in Hebrew and soar in English? I ask myself this innumerable times, after having lived in Israel for twenty-five years.

As a child of immigrants who themselves were children of immigrant refugees, I was comfortable with hybridity and resisted a simplistic binary.

In the preface to Cynthia Ozick’s 1976 book, Bloodshed and Three Novellas, she writes about her relationship to English. She says, “English is my everything, now and then I feel cramped by it… A language, like a people, has a history of ideas; but not all ideas; only those known to its experience. Not surprisingly, English is a Christian language. When I write in English, I live in Christendom.” And she reminds us that Henry James was none too happy when the children of Jewish immigrants began to make their way into English. They brought with them all sorts of Eastern European influences that he would have rather they left behind. So when Jewish writers like Ozick — like me — write in English, we are portraying ourselves through a filter which to some degree resists us.

When writing Hebrew in Israel, there is the pulling forward of a thread that starts in the Bible, and runs through to the medievalists Ibn Gvirol and Yehuda HaLevi; to the resurrectionists Bialik, Tchernechovsky, and Goldberg; on through to today’s books where the colloquial dominates. When I write in English, I pull from Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Austen, and Hemingway all the way up to today, where Jews have taken their place at the table. Four out of fourteen American Nobel Prize winners in literature have been Jews – the most recent being Bob Dylan. And two of them did not write in English: Isaac Bashevis-Singer (Yiddish) and Joseph Brodsky (Russian). On the other hand, Saul Bellow, the first American Jew to win a Nobel in 1976, was so certain he belonged to English literature that he never worried English literature might not belong to him – a strong contrast with Ozick’s ambivalent observations.

I situate myself peculiarly between Ozick and Bellows. On the one hand, my place within this long chain of English literature makes sense to me since I was born and raised with English in America. So like Bellow I assume belonging. But like Ozick I am sensitive to what English is not – it is not the language of the Jews. And this has become clearer to me since I moved to Israel.

Because I do not read much in Hebrew, I can barely compose a text message in the language of my country without making hilarious mistakes; I am painfully aware all the time that the official language of the Jews – both in terms of political statehood and cultural, religious, and national legacy – is not something I live inside of, like I do English. And this makes me confront my insider/outsider status every day.

So when Jewish writers like Ozick — like me — write in English, we are portraying ourselves through a filter which to some degree resists us.

It’s the difficulty of a new alphabet that sabotages my efforts in Hebrew. A few years back I managed to read Dorit Rabinyan’s novel, Geder Haya, translated into English as All the Rivers. It is a powerful story of a love affair between an Israeli Jewish woman and a Palestinian Muslim man in New York City. And I read it because Dorit is a friend and I didn’t want to wait – which is what I usually do – for the English translation to come out. And so I read, slowly, methodically, and enjoyably. I told Dorit that it was both strange and thrilling for me to read New York in Hebrew. And as I was telling her this, I realized this is exactly what I do when I write Israel in English. The scepter of Chaucer is there in the streets of Haifa and Tel Aviv. And Milton’s Christian exploration of the world’s vices and virtues is there in the opening scene of Make it Concrete. I like to think that echoes of past civilizations are woven together as English words, Israeli landscapes and characters merge and emerge from the sentences. English is my language of scholarship and fiction. It is my language when I connect to America, my other home across the Atlantic. Hebrew at the supermarket. English at my desk.

When Joseph Brodsky won the Nobel Prize in 1987, he was asked: “You are an American citizen who is receiving the Prize for Russian-language poetry. Who are you, an American or a Russian?” Brodsky responded: “I’m Jewish; a Russian poet, an English essayist – and, of course, an American citizen.” Identifying himself first as a Jew and secondly as a person who writes in one language or another; this may be one of the common markers for Jewish writers, even those who live in Israel. This is the post-colonial paradigm Axel was keen on exploring, and with this in mind, I have thought a lot about Salka Viertel’s quote: “I have been an outsider in Vienna, in Germany, and in Hollywood. And I have accepted this fact rather cheerfully. Perhaps after all it is not so bad for a Jew to be an outsider.”

Writing in English, even in the country where I, as a Jew, have ancestral roots, where the majority of Jews live within the magically revivified ancient language of Hebrew, maintains my outsider status. And maybe it is not such a bad thing after all for a Jew like me, like Isabel Toledo, to be an outsider – even in the land of Israel.

Miryam Sivan is a former New Yorker who has lived in Israel for twenty-five years. She teaches literature and writing at the University of Haifa. In addition to scholarly articles and a book-length study on Cynthia Ozick, she writes short and long fiction. Sivan is the author SNAFU & Other Stories, and a recently published novel, Make it Concrete.