Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Illustrations by Helen John, from All-of-a-Kind Family, by Sydney Taylor, Wilcox & Follett, New York, 1951.

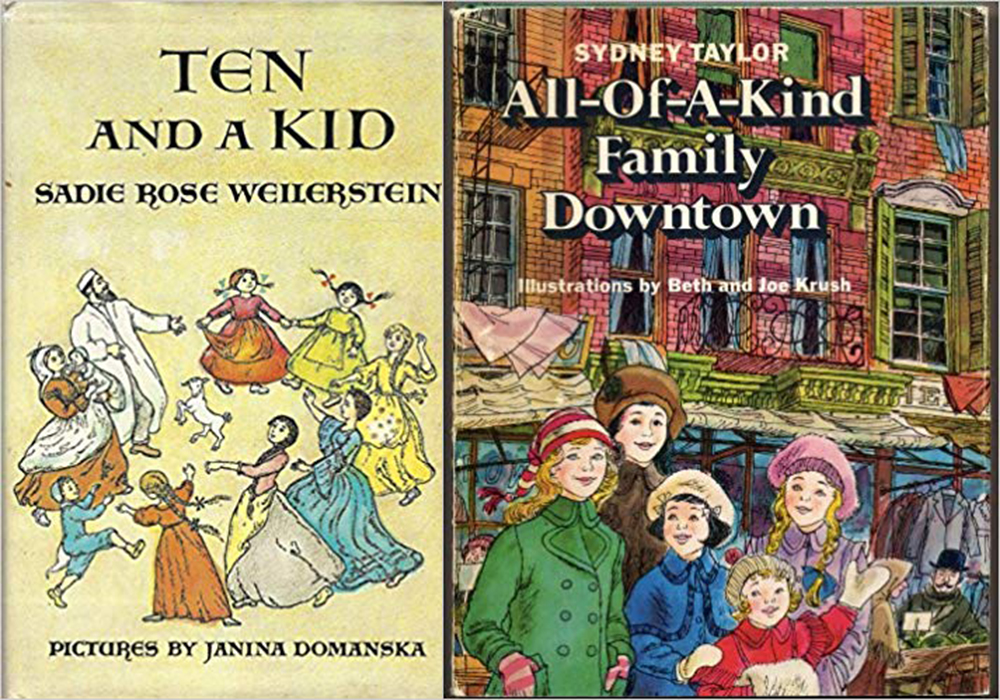

Sukkos and Simchas Torah (the Ashkenazic pronunciation) are two of the most colorful festivals of the Jewish year, each reenacting pivotal moments in Jewish history. As in virtually all Jewish holiday observances, beliefs about appropriate gender roles influence how children participate in these joyous rituals. However, questioning those norms, whether implicitly or more boldly, is not new to the world of Jewish children’s books. Two beloved classics, All-of-a-Kind Family Downtown (1972), by Sydney Taylor, with pictures by Beth and Joe Krush, and Sadie Rose Weilerstein’s Ten and a Kid (1961), illustrated by Janina Domanska, each anticipates changes to come in Jewish life in the area of gender roles. In both books for middle-grade readers, children observe and question the inconsistencies which dictate what girls and boys may do within their socially prescribed spheres. While the American All-of-a-Kind girls are content with encouraging some changes within the structures of tradition, Reizel, the heroine of Ten and a Kid, chafes at the limits on female spirituality in her Lithuanian shtetl and demands to know why male authority is so resistant to change. The halakhic (legal) reasoning that exempted women from many commandments seems to her a transparent means of excluding them from the most profound connection to their faith.

Sydney Taylor (1904−1978) was the matriarch of Jewish American literature — the author who provided a new and affirmative version of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women for the children and grandchildren of immigrants. In the five books of the All-of-a-Kind series, echoes of Alcott’s four main protagonists can be found in Ella, Henny, Sarah, Charlotte and Gertie. Instead of celebrations of Christmas in nineteenth-century New England, readers follow the Jewish calendar of New York’s Lower East Side and the Bronx in the early twentieth century. When it’s time to build a sukkah in All-of-a-Kind Family Downtown, different talents are required — from physical strength to artistic creativity. As in other books in the series, non-Jews play a prominent role — emphasizing that both fidelity to tradition and assimilation in American society were part of immigrant life. The girls’ father welcomes their enthusiasm about building the sukkah, but suggests that some male physical strength is needed, “‘You know, Mama,’ Papa remarked, ‘our girls are wonderful helpers. But what I need is someone for the heavier work.’”

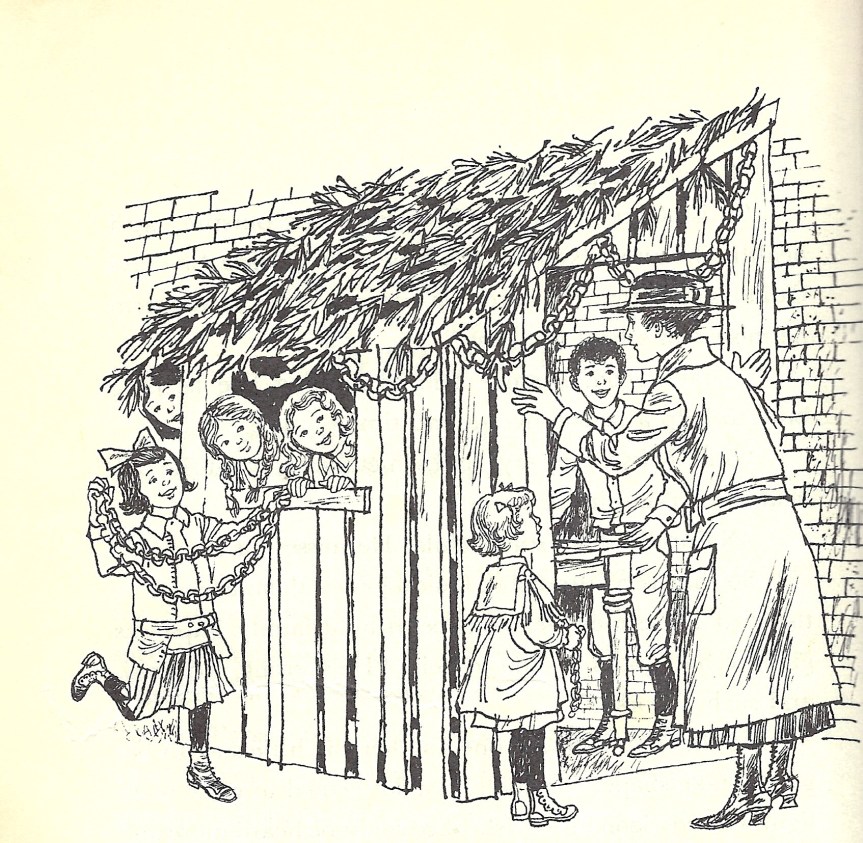

That someone is Guido: an Italian-American neighbor, whose family is poor, vulnerable, and receives support from the local Settlement House, where social workers help immigrants acculturate to their new home. Guido is glad to offer his muscles, but insulted at the suggestion that decorating the sukkah is part of the deal, “He watched the girls busy themselves with scissors, colored paper, and paste. ‘Making silly old paper chains and stuff…That’s for sissies!’” Rather than have the girls object, Taylor chooses to let them gently ignore Guido’s hostility towards their distinctly gendered contributions to the sukkah.

When Miss Carey, the Settlement House nurse, arrives to admire the beauty of the booth’s construction, she remarks on its sturdiness and its delicacy, “The strong wooden walls, the homemade table and benches…the scent of the fresh greenery festooning the walls.” The white line drawing emphasizes the sukkah’s detailed perfection, showing Guido grinning with delight in the center of the house he has helped to build, while the girls stand behind and around him. Two sisters peer out the window, one is partially glimpsed from behind the sukkah, and another stands at the side holding the paper chain which Guido had deemed girlish. Only the youngest and smallest, Gertie, stands in front, looking up at Miss Carey. Guido stands front and center, proud of his contribution, while Gertie, the youngest sister, looks up at Miss Carey in admiration. In an America where women still did not have the vote, activists and social service workers like her were important female role models because they showed women in roles outside of the home and domestic responsibilities.

When Papa later brings the lulav and esrog into the sukkah, he explains the meaning of the holiday clearly, without condescension. When Gertie admits that she has forgotten the story, he reassures her, “That’s all right, Gertie…the story can always bear repeating.” Similarly, when Simchas Torah arrives at the end of Sukkos, Papa responds to Charlotte’s confusion about the holidays’ proximity by praising her intelligence, “That’s a good question, Charlotte, and it deserves a good answer.” With great seriousness, he instructs his daughters on how to perform the mitzvah of shaking the lulav and holding the esrog—a mitzvah which is not required of women in Jewish law; as a time-bound commandment, it would conflict with their more important duties of childbearing and maintaining a home. In practice, this interpretation almost always served to justify the exclusion of women from ritual life.

In practice, this interpretation almost always served to justify the exclusion of women from ritual life.

As the week of Sukkos concludes, the family goes to their synagogue to welcome Simchas Torah. There is a scene in which Taylor acknowledges that change will come within the girls’ lifetimes. The scene begins with solemnity; words such as “awe,” “reverently,” and “precious” are used which describe the privilege and responsibility of receiving the Torah. Then, the Torah scrolls come out of the ark in a riotous scene captured by the illustrations, where every space is populated by overlapping worshippers, old and young, male and female. As Papa explains, “It’s God’s party and everyone is invited!” Picture and text reiterate the same message: “The curtain separating men and women was thrust aside, and so contagious was the revelry, many of the younger women joined the dancers…Only the older women remained seated on the benches…” Taylor’s enthusiastic description of this Lower East Side celebration assures readers that life in America will bring positive changes for Jewish women.

Reizel, the little girl living with her parents, five sisters and two brothers in a Lithuanian town in Weilerstein’s Ten and a Kid, could well have been a cousin to Taylor’s immigrant family. She is not exposed to the challenging climate of America, where Jews are largely free from outright persecution, although subject to both the rewards and the pressures of assimilation. Although some Eastern European Jewish women did advocate for changes in traditional ways of life, they had far less support within their communities. Weilerstein (1894−1993), an author, teacher, and homemaker married to a Conservative rabbi, chose to give Reizel a strong and persistent voice denying that oppression of women and girls needed to be a permanent feature of Jewish observance.

The festival of Sukkos is a source of frustration to Reizel, so much so that she astonishes her family by suggesting that they not build a sukkah at all. She pointedly attacks a central paradox of Jewish holidays for women and girls; for them, service to males consumes any meaningful opportunities for internalizing the festival’s message:

That’s just the trouble. Girls don’t sit in the sukkah. Only boys and men do. Boys get everything. They don’t have to wait their turn to go to school. They sit in the sukkah. It’s not fair.

Reizel’s frustration is exacerbated by the fact that her younger brother will be allowed to attend school, but she will not, one more example of male privilege. She cannot accept the perennial argument that sitting in the sukkah is not actually forbidden to women, but is not required — a meaningless distinction for the girls and women cooking and serving food while men study and pray. A small picture of Reizel holding the ladder as her father hammers the sukkah’s roof illustrates the intensity of her aspirations to look up at the heavens rather than down at her domestic tasks.

K’tonton riding a lulav, in Sadie Rose Weilerstein’s in K’tonton’s Sukkot Adventure

Reizel ultimately has the good fortune to learn from her mother’s friend, Hannah Rachel, about an inspiring alternative from the past — the famed Holy Maid of Ludimer. This historical figure was a nineteenth-century Jewish woman, so deeply pious that she took on the mitzvot of both tallis and tefillin, contradicting accepted societal norms. Reizel is overwhelmed with excitement upon learning of this precedent; a woman who managed to defy oppression by appropriating the very signs of religious commitment which men alone had been allowed to assume. Reizel confronts her father, who at first responds with humor, which Reizel feels as belittling. When he asks if she plans to become the next Holy Maid, Reizel answers for generations of girls and women, “I have asked you a question and you should answer it, not tease me.” In contrast to what is expected, her father admits that she is right, and concedes the dignity of her point by answering. Reizel may accept the obligation to sit in the sukkah.

When he asks if she plans to become the next Holy Maid, Reizel answers for generations of girls and women, “I have asked you a question and you should answer it, not tease me.”

When Simchas Torah arrives, Reizel and her family attend synagogue. Unlike the girls of All-of-a-Kind Family Downtown, there is no public boundary-breaking; only men dance with the Torah. Yet the next day, her parents inform her that they have spoken with Reb Gershon, who teacher religious studies to boys in his heder. This saintly man has agreed to make an exception and teach Reizel, as well. Reizel has been trying to learn independently, and the rabbi determines that “A child who finds her way into a book without a teacher deserves to have a teacher to take her further.” In spite of the cultural distance between Taylor and Weilerstein’s stories of holiday observance, both books embody this profoundly Jewish belief.

Both books reflect a long tradition of women seeking to enlarge their experience within Jewish rituals, whether quietly or more assertively; both authors look back at the past with the knowledge that change will come. The five girls of All-of-a-Kind Family Downtown enjoy glimpses of the progress that life in America will inevitably bring, while in Ten and a Kid Reizel needs to actively summon a better future. Each of these classic Jewish children’s books would be perfect to discuss over a meal in the sukkah, where everyone is certainly invited.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.