Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Lesléa Newman is the author of more than seventy books for children and adults. Many of her books explore themes of particular relevance to the LGBTQ community, while others offer her own interpretations of the Jewish experience. We spoke about some of her most acclaimed works, and about her engagement with issues of representation in books for young people. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Emily Schneider: Back when you published A Letter to Harvey Milk, which had some deeply moving short stories and was very favorably reviewed, you had a wonderful quote from one of the stories where a character, Rachel, sums up the challenges of her identity in the statement: “Being a lesbian is lonely…Being a Jew is lonely…Being alive is lonely.” The matter-of-fact brevity of that definition still seems stunning to me. Do you now see it as dated, or do think it is still a reliable summary in some ways of a gay Jewish woman’s life today?

Lesléa Newman: First of all, I’m a little stunned that I was so wise when I was thirty-years-old! I don’t really remember writing that but it’s actually a profound statement that I believe is true. I think there are moments in every human being’s life when one feels lonely, and I really like this quote from Maya Angelou: “I write out of the black experience about the human experience.” That’s kind of how I feel. I write out of a Jewish lesbian experience about the human experience. So, yes, I definitely think that quote is still relevant today.

ES: The Angelou quote is wonderful. It gets to the core of one of the things I’d like to speak with you about — the specific and universal aspects of your work. Even though you have written over seventy books, you will always be known for Heather Has Two Mommies, originally from 1989, reissued in 2015, because it was revolutionary in presenting a role model for children who had not seen themselves in books before. Can you bring us back to the climate for LGBTQ books for kids back in 1989? How did you come up with the idea for that groundbreaking book? And you must have met with some resistance, what gave you the chutzpah to persist?

LN: There was no climate because no LGBTQ books for kids existed. The story of how I came up with the idea for the book has become kind of a legend. A woman stopped me in the street in Northampton, Massachusetts, and said “I don’t have a book that shows a family like that…somebody should write one.” I became that somebody. I thought about my own experience of growing up as a Jewish child in the 1950s and 1960s and never seeing myself in a book. I had a pretty traditional childhood in terms of reading, like Dick and Jane and, when I got older, The Bobbsey Twins. There was absolutely no book about a little girl eating matzo ball soup with her bubby and lighting candles on Friday night. So, I knew the loneliness of that. When I wrote the book, nobody would publish it. I sent it to at least fifty publishers, and what gave me the chutzpah is coming from a long line of fierce women. My maternal grandmother, whom I was very close to, always said, “Just because they said no to me, do you think I’m finished?” So that’s kind of how I live. A friend of mine, Tzivia Gover, and I decided that we would co-publish the book together. The book came out in 1989 by In Other Words press, which was owned by Tzivia, and six months later Alyson Books became the official publisher of the book.

When I wrote the book, nobody would publish it. I sent it to at least fifty publishers, and what gave me the chutzpah is coming from a long line of fierce women.

ES: Two of the main changes from the original book to the later editions were the decision to remove the short section on alternative insemination, and, more significantly, to change Heather’s emotional response to having two moms but no dads, in the 2015 revision. What prompted those changes?

LN: I ultimately decided that the alternative insemination scene didn’t belong there. If a scene can be taken out without affecting the rest of the book, it doesn’t belong there. Kids like forward motion in a book. I also changed the scene in the original edition where Heather cries when she realizes that she is the only child in her class without a daddy. It is a wonderful opportunity as an author to be able to edit your own text. Twenty-five years later, I realized there was nothing to cry about. Heather’s realization is just an observation. It doesn’t carry that sense of emotional devastation. A kid knows that a family is the people who love them, who take care of them, and who keep them safe in the world.

ES: In 1997 you had a piece in The Horn Book which ties together two parts of your identity which have informed your work, being Jewish and being gay. How do you think the situation today has changed for Jewish, gay, and gender non-conforming kids in finding books where they can see themselves?

LN: Being raised as a Jew was great preparation for being a lesbian because I was surrounded by strong Jewish women, and I was taught early on that community and social justice were very important. I carry those values through my whole life as a Jew, and then also in the LGBTQ community. You know, I remember the first time I saw a Jewish children’s book very clearly. I was in a bookstore at about twenty-seven-years-old and it was The Carp in the Bathtub, a wonderful classic, right? I pulled it off the shelf and looked at it. I saw a family just like mine, and in the bookstore, I began to cry; I’m tearing up now, actually, because it was so meaningful to me. So that is why when this woman asked me to write Heather Has Two Mommies, I immediately said yes even though I had never written a children’s book before. Now there are hundreds of picture books that feature Jewish families and, as you know, I’ve written over a dozen myself. So, I’m very pleased about that. And in terms of LGBTQ picture books, I would not say there are hundreds, but there are dozens.

I pulled it off the shelf and looked at it. I saw a family just like mine, and in the bookstore, I began to cry; I’m tearing up now, actually, because it was so meaningful to me.

ES: In The Horn Book piece, you observe that ““Heather Has Two Mommies and “Daddy’s Roommate” are not about sex. They’re about families. Clearly it’s the adults, not the children, who can’t take the sex out of homosexuality. Do you think people protesting or feeling uncomfortable with those books today are any less obtuse about that fact, or has little changed?

LN: The closed mind is a closed mind. These books are about families and inclusiveness. If someone is going to see that as controversial, I don’t know how to fix that, except by putting out books that show all types of children and all types of families. When I write a children’s book, my goal is to have the child reader feel good about themselves. The protests stem from fear, from the desire to control your children. You don’t know who you give birth to — they might be a child who grows up part of the LGBTQ community. Your job is to respect, accept, support, and celebrate them.

ES: You put that very eloquently. Speaking of books which bring tears to your eyes, I really love My Name is Aviva. You received very positive reviews for it, and most of them were sensitive towards its universality. The little girl in the book has a weird, Jewish name and she wants to have an ordinary name that no one will mock. Some reviews categorize the book as almost exclusively Jewish. One recommends it specifically for Jewish collections. Another, from Booklist Online, actually praises it with the phrase, “Although not overtly religious, this will be most welcomed by Judaic collections.” There’s a whole tradition of modern picture books about children dealing with the difficulty of having an ethnic name, including last year’s Alma and How She Got Her Name by Juana Martínez-Neale, and Yangsook Choi’s The Name Jar, from 2003. It is rare to see those books reviewed as exclusively for Hispanic or Asian children. Do you think that Jewish books are still, even to well-intentioned readers and professionals, less intuitively accessible?

LN: So, this is an interesting issue and I will just preface it by telling you a little anecdote. I was in a workshop about diversity many years ago. The workshop leader was trying to make a point, and she said, “If you like strawberry ice cream, go to the left side of the room. If you like pistachio ice cream, go to the right side of the room.” People divided. She said something like, “If your favorite color is blue, go to the right side of the room, if your favorite color is red, go to the left side of the room,” and there was some overlap. And then she said, “If you are a person of color, go to the left of the room, if you are a Caucasian person, go to the right side of the room.” The attitude of the room changed; people weren’t laughing anymore. So people divided, and there was a group of people who, without saying anything to each other, went to the middle of the room. The workshop leader was very puzzled. She asked, “Who are you?” and I said, “We’re the Jews.” Without knowing anything about anybody else, all of us grouped together. I said to myself, “These are my people, and we don’t know where to go.” So, in the “We Need Diverse Books,” movement, it is just as you said. The Jewish book about names is not seen in the same way as others with the same message, as a book about learning to have pride in your name. We are not purely part of the mainstream world, and yet, we’re not seen in the same way as other excluded groups. We should be included more in the conversation about diversity.

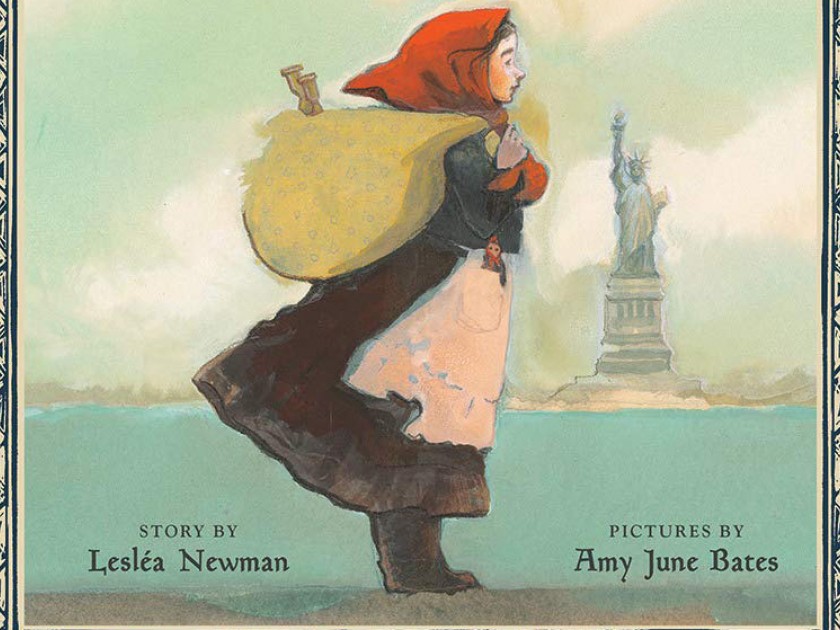

ES: Your most recent book, Gittel’s Journey, is deeply Jewish, but at the same time it’s such a universal narrative about immigrants. Given the fact that there are so many immigrant narratives in children’s books, what motivated you to tell your own version of the story?

LN: I’ve seen many reviews about Gittel’s Journey, and I don’t think one has said it is only appropriate for Jewish libraries and readership. It’s a Jewish story, but it also has universal appeal because this is a country of immigrants. It’s also a story that I grew up with, based on my godmother’s mother, whose name was Sadie Gringrass. It was just one of those stories which was in my blood and my bones, and it was lying dormant until, recently, I saw a photo in the news of a boat of Syrian refugees washing up on the shores of Turkey. I looked at the faces of these people who are so hopeful and distraught at the same time. I remembered the story, and decided to write it. Gittel’s character is also based on my grandmother, Ruth Levin, who came to this country in 1900 with her mother and their Shabbos candlesticks, which I now own. I think that every immigrant story deserves to be told, just like for every Holocaust survivor and victim. They all have a common thread, but they’re all unique, because every individual is unique.

It’s a Jewish story, but it also has universal appeal because this is a country of immigrants.

ES: In some ways, Gittel’s Journey seems like an homage to classic picture books. Not only Amy June Bates’s rich color palette and the woodcut frames around the text, but also the high proportion of words to images, a less common choice today than in the past.

LN: Whenever I write a book, I don’t really think about the length of the text. I just write the story that needs to be told in the way that it needs to be told — it’s not a preconceived idea. I let the story take me on its own journey. I was very lucky, because my wonderful editor, Howard Reeves, shared my vision and found Amy June Bates, who I think is a genius, and she clearly put her heart and soul into this book. It’s a picture book for slightly older readers, maybe six- to nine-year-olds, but adults have taken to the book and love it, too.

ES: I’d like to go back for a minute to tie together some of our discussion. The eminent scholar Rudine Sims Bishop famously used the metaphor of mirrors and windows to make the point that children need to see themselves in books; that’s the mirror. But they also need to see windows into the experiences of other groups different from their own. One question I have is, how exact a reflection does the mirror need to be in order for children to identify with characters in books?

LN: I heard from a little girl who wrote me a thank-you letter for writing Heather Has Two Mommies. She said, “I know that you wrote it just for me.” I happened to know that this child, whom I had met, was African-American. Heather is white, but Tasha was convinced that I wrote the book just for her. So, children cross gender lines and racial lines to put themselves right in the books. Kids want to see themselves in books so they will go the extra mile in order to do so. As a writer, I work extra hard to make that happen.

ES: The second part of my question concerns the windows. In order to see through a window, you have to be willing to walk up to someone’s house and look into that window. Are non-Jewish caregivers and educators as motivated as they might be to look into Jewish windows, to give children that opportunity to understand us?

LN: That is a tough question. I have to say, some people will even have an issue with my talking about Jews as a minority group. I have talked to other Jewish children’s book authors who don’t think that the diversity in children’s book movement feels the same way about Jewish children’s books as they do about books from other communities. Maybe the exception is around the holidays. By the holidays, I mean Passover and Hanukkah, of course. I don’t think there are many people out there looking for a book about Simchat Torah.

I don’t want to define my identity around persecution, but it’s a real factor in our history. There is a time and place to work within one’s own group, and a time and place to reach out and work in coalition.

ES: Especially given the climate of our country right now, are you optimistic about how we as Jews, without diminishing the particular experiences of other groups, might be part of the conversation? Or should we focus more on reaching our own community?

LN: I think the answer is both. Looking at our five thousand year plus history, we have always been considered different. I don’t want to define my identity around persecution, but it’s a real factor in our history. There is a time and place to work within one’s own group, and a time and place to reach out and work in coalition. Because until all of us are free, none of us are. It’s especially important to have difficult conversations with an open heart and an open mind. I have a book coming out next year called Welcoming Elijah: A Passover Tale with a Tail. It takes place during the seder, and there is a line about welcoming friends to the seder. Originally, there was an illustration of a boy with a mom and dad standing in the doorway. I asked my editor, “Why is that the default?” I would just like the child to open the door. That way, a child with a mom and a dad, or a child with two moms or two dads, or a child from a single-parent household, or a child living with grandparents, can still see themselves. Because you don’t know who’s inside.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.