Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

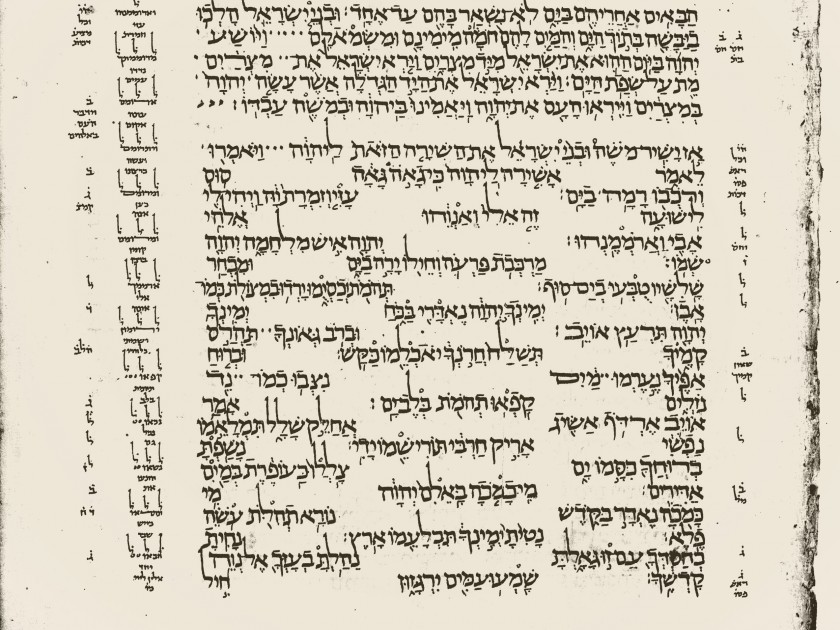

Song at the Sea (Exodus 15), Leningrad Codex, 1009 CE, the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible in Hebrew. The photo shows the beginning of the Song at the Sea (Exodus 15:1 – 14) and the prose verses from the end of the preceding chapter. In biblical manuscripts, the poem is written stichographically, lines are laid out in a pattern. Source: archive.org.

The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) is often considered to be the anthology of anthologies. It is the most ancient of all Jewish collections, and has spawned other essential anthologies such, as the Siddur, as more than 80 percent of the Jewish prayer book draws on the Bible.

Anthologies are typically curated by a clear organizing principle, but here, the Hebrew Bible diverges. The biblical canon appears to deny any intentionality of anthologizing. It contains a collection of texts written and compiled over nearly one thousand years, mostly from the land of Israel, but not entirely; primarily in Hebrew, but not completely; and encompassing many genres, including history, law, myth, novellas, poetry, philosophy, and more — all without a definable and consistent organizational method. How could it change the way we read if we organized the texts, say, topically, or by genre, rather than as we are used to seeing them in the Tanakh? What new possibilities for interpretation and understanding might reassembling the canonical Jewish material present?

The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, Volume 1: Ancient Israel, from Its Beginnings through 332 BCE takes a different approach from the Tanakh itself. Volume 1: Ancient Israel collects and organizes biblical texts by genre and integrates into its collection additional artifacts — including inscriptions, coins, letters, and material culture — produced largely by ancient Israelites from the biblical period.

In Volume 1: Ancient Israel, the editors extract the poetry of the Hebrew Bible from its narrative contexts and present it together. New juxtapositions create opportunities for fresh insights and interpretations into the meanings of specific texts and their significance within the canon.

The first poetry entries, now set side-by-side, are “The Song of Deborah” from Judges 5 and “The Song at the Sea” from Exodus 15. At first glance, the two poems have many similarities. Both poems are among the oldest passages in the Hebrew Bible, likely dating to the 11th or 10th century BCE. They both qualify as Victory Songs, a type of ancient Near Eastern poetry. Each celebrates a national victory and salvation that was narrated in prose immediately preceding each poem. Quite intentionally, the rabbis legislated that the two texts be read together in the synagogue on Shabbat Shirah (the “Sabbath of Song”) — the shabbat on which Exodus 15 is read from the Torah and Judges 5 from the Prophets. It is aptly named because of the two songs.

The similarities continue in the invocations of both songs, praising God and utilizing poetic parallelism — that is, short lines that employ synonyms to express the same idea or image, often with intensification of the idea or motif — a defining feature of biblical poetry.

Deborah and Barak sing of victory, declaring to all who hear:

“Hear, O Kings! Give ear, O potentates!

I will sing, will sing to the Lord,

Will hymn to the Lord, the God of Israel” (Judges 5:3).[1]

Similarly, Moses and the Israelites sing:

“I will sing to the Lord, for He has triumphed gloriously … ” (Exodus 15:1)

The differences though are thrown into relief when the texts are read side-by-side, as they appear in Volume 1: Ancient Israel. These differences include the role of the victory event within Israelite history, the human role in salvation, and the role of women.

The image of women as singers and drummers may have been common, as seen from this figure of a woman playing a frame drum, and others like it. Collection of The National Maritime Museum, Haifa. © Zev Radovan / BibleLandPictures.com.

The Role in History

The Song of Deborah, while celebrating a specific victory over the “Kings of Canaan”, situates this event within the trajectory of Israelite history:

“O Lord, when You Came forth from Seir,

Advanced from the country of Edom,

The earth trembled;

The heavens dripped,

Yea, the clouds dripped water,

The mountains quaked—

Before the Lord, Him of Sinai,

Before the Lord, God of Israel” (Judges 5:4 – 5)

The present victory over the Canaanites is depicted as a single event in the larger context of God’s revelation to Israel, including the revelation on Mount Sinai.

In contrast, the Song at the Sea is focused specifically on deliverance from Pharaoh and the Egyptian army at the Sea of Reeds; the fate of the Egyptians is described poetically:

“Horse and driver He has hurled into the sea [ … ]

Pharaoh’s chariots and his army

He has cast into the sea;

And the pick of his officers

Are drowned in the Sea of Reeds.

The deeps covered them;

They went down into the depths like a stone” (Exodus 15:2, 4 – 5).

Human Role in Deliverance

While Moses plays a central role as God’s agent of deliverance throughout the entire exodus narrative, in the Song at the Sea, his role is relatively diminished to that of leader of the song. Instead, all credit is attributed to the God of Israel, who is presented as a warrior (Exodus 15:3) against the army of Pharaoh. The image of the God of Israel as a God of War and all-powerful savior would have been familiar to ancient Israelites as it is a common representation of the gods of the ancient Near East and is present in the oldest biblical material. This image may have been a comfort, even as it may offend our modern theological sensibilities.

Rather than focusing only on God’s role in the tribes’ deliverance from the Canaanites, the Song of Deborah also praises the human actors in their own salvation, especially Deborah. The people call upon Deborah to rescue them at a time when “Deliverance ceased, / Ceased in Israel” (Judges 5:7):

“Awake, awake, O Deborah!

Awake, awake, strike up the chant!

Arise, O Barak;

Take your captives O son of Abinoam!” (v. 12).

Likewise, deliverance was a group effort: “The Lord’s people won my victory over the warriors” (v. 13), as many of the tribes of Israel have come to the people’s defense (vv. 14 – 18). Further, the primary victory is credited to Jael “most blessed of women” for killing the enemy general (vv. 24 – 27).

The Song of Deborah, in addition to its poetic beauty, is important for its immortalization of women’s roles in the victory, particularly Deborah and Jael’s.

The Role of Women

The Song of Deborah, in addition to its poetic beauty, is important for its immortalization of women’s roles in the victory, particularly Deborah and Jael’s. It is also unusual because the song itself is attributed to a woman. Deborah is a prophet and a judge (or tribal “chieftain”). Her role in this victory is further developed in the preceding prose account, in which the general Barak is unwilling to enter into battle without her (Judges 4:8). And while the details and straightforward prose report of Judges 4 (not to mention that it precedes the song in a printed Bible) lead the reader to believe it is the “original” account, the archaic Hebrew of the poem reveals that the poetic version is actually much older than the prose version.

At the Sea of Reeds, the presence of women is mentioned in the celebration of victory only once Moses’ song is complete. After the Song at the Sea ends, the narrative resumes and notes that Miriam, also a prophet, and sister of Moses and Aaron, takes up her timbrel and leads the women in song:

“Sing to the Lord, for He has triumphed gloriously;

Horse and Driver He has hurled into the sea” (Exodus 15:21).

While the iconography of Miriam with her timbrel has become a powerful feminist image in the modern period, here it reads as something of an afterthought. The juxtaposition of the two songs throws into further relief the primary role that Deborah plays in Judges, in contrast to Miriam’s relatively minor role at the crossing of the sea. At the same time, the inclusion of any mention of Miriam and the indicated reprise of the poem demonstrates that the fragment was important enough in the culture of ancient Israel to be memorialized by its inclusion. The fact that ancient compositions are incorporated into the biblical narrative means that they were culturally important to ancient Israel. The words attributed to Miriam echo the first line of the primary Song at the Sea, but instead of Moses’ “I will sing to the Lord … ”, Miriam uses the imperative “Sing to the Lord …” calling the women to join her in song, illustrating that the poetic expression of jubilation belonged to the women to and not only Moses and the men.

Reading these poems together, and separating them from their prose contexts within the biblical canon, brings new insight to the pieces. Without the prose narratives, we read the older accounts of what happened on their own terms and, in the case of Judges, the song is different than the prose version.

These biblical poems, among others, can be found under Poetry on The Posen Digital Library.

[1] All biblical quotations are from Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. Copyright 1985 by the Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia. https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/jps/9780827602526/

Alison L. Joseph is Senior Editor of The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization. She earned her Ph.D. in Near Eastern Studies from the University of California, Berkeley and her M.A. in Jewish Studies from Emory University. Her first book Portrait of the Kings: The Davidic Prototype in Deuteronomistic Poetics received the 2016 Manfred Lautenschlaeger Award for Theological Promise.