Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

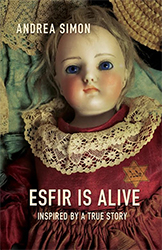

Earlier this week, Andrea Simon wrote about transforming her family memoir into a novel and the research she puts into fiction writing—particularly for her new book, Esfir Is Alive. Andrea is guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

25 years ago, when I finished my first semiautobiographical novel, my mother, a highly critical woman, begged me to read it. I put her off, finding all kinds of excuses, thinking as only a naive first-book author would that my novel would be published soon and she could read it then. But I had not anticipated that my mother would be relentless in her quest, finally swearing that she wouldn’t utter a word of negativity. So one Friday evening, I left the manuscript on her kitchen table, with a note, “Please be kind.”

All that weekend, I sweated. My heart thumped every time the phone rang. I worried that my mother would recognize the nuclear family of the young protagonist summering in New York’s Catskill Mountains. Surely she would remember the startling familial events of my childhood, no matter how I embellished them; she would cringe at the character’s motives and descriptions, cutting through my disguises and convolutions.

After an agonizing few days, my mother called and said, “I have only one criticism.”

I knew I couldn’t trust her. “What is it?” I said, upset with myself for even asking.

“I don’t know why you named the mother Estelle,” she said. “My own name is so much better.”

This exchange exposed a few lessons to follow throughout my writing career: sometimes reality is preferable to fiction; sometimes the people you know are flattered to be made into a character; and sometimes those real-life counterparts are more emotionally evolved than anticipated.

As a person who freely gave people “a piece of her mind,” my mother was my best source of material. In numerous personal essays, I recorded her outlandish comments (“This book was so bad, I can’t understand why yours isn’t published”) and motherly advice (“Marriage is not to be happy”). My larger-than-life grandmother, married three times (to a rabbi, a millionaire, and an owner of a drag cabaret), has been the inspiration for several works.

But not all relatives are so forgiving. Often, when the inspiration is someone displaying unsavory characteristics, I am tortured by possible recriminations. In general, I am heartened by the advice of Anne Lamott, who wrote in her classic, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life,“You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”

Friends don’t escape my pen, either. There is Penny from high school, who says “in other words” before she speaks and my childhood friend Joanie who provoked her eye doctor to say to her, “I hate you.” I could go on; there is certainly no shortage of material.

When I was interviewing my family for a memoir that interspersed personal stories with historical events from the twentieth century, I became fascinated by the voices of my mother and her siblings, nine in all. Born in Poland and escaping extreme poverty and discrimination, they came to America in time for the Depression and then World War II. Many were formed by economic need and antiquated roles. Two of the males died early, one in a wartime plane crash, the other from suicide.

I recorded family stories on my tape recorder and took voluminous notes. I respected confidences, especially from my great-aunt Sophie (real name disguised) who kept a secret for sixty years. She unburdened herself to me, knowing I was writing our family history. But I was careful not to include those aspects that gave her the most anguish. When the book was published, Sophie’s daughter said that her mother was extremely hurt about my revelations.

“But she gave me her permission,” I protested. “As a matter of fact, I left out any detail that involved her participation.”

“Still,” she said, “it was shocking for her to see it in print.”

Since the publication of my family memoir, I have written other fictional and autobiographical works featuring characters based on family members, as well as friends and acquaintances. Generally, unless the person is dead or being eulogized, I change the name and obvious physical characteristics. However, an amateur sleuth could guess the initial role model by recognizable anecdotes or behavior. The people in my life form the people in my writing, no matter how I disguise them. They are my prototypes; their experiences underpin the themes and motivations of my “oeuvre.”

Mostly, though, relatives and friends are good-natured about their presence in my work. They are flattered and come to my readings bragging about their likenesses. Though my sister often disputes my memories, she signs her e‑mails, “Love, Brenda,” the name of her fictional counterpart. Of course, there are others who can’t wait to tell me that I got their professional title or birthplace wrong (even if it’s fiction).

Mostly, though, relatives and friends are good-natured about their presence in my work. They are flattered and come to my readings bragging about their likenesses. Though my sister often disputes my memories, she signs her e‑mails, “Love, Brenda,” the name of her fictional counterpart. Of course, there are others who can’t wait to tell me that I got their professional title or birthplace wrong (even if it’s fiction).

My cousin Bernice once accused me of misrepresenting her. I resorted to a white lie and said, “Oh that wasn’t you. It was your sister, Diane.”

Surprisingly, Bernice, a longtime sufferer of sibling jealousy, said in a choked voice, “Really?”

I didn’t answer, but I’m thinking of writing about the time Bernice drove 500 miles to a bar mitzvah on the wrong weekend. I may even use her real name.

Andrea Simon is the author of the memoir Bashert: A Granddaughter’s Holocaust Quest, the new novel Esfir Is Alive, and several stories and essays. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the City College of New York and lives in New York City.

Related Content:

Andrea Simon is the author of the memoir BASHERT:, A GRANDDAUGHTER’S HOLOCAUST QUEST, her recent novel ESFIR IS ALIVE, and several published stories and essays. The recipient of numerous literary awards, Andrea holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the City College of New York where she has taught writing. She lives in New York City.