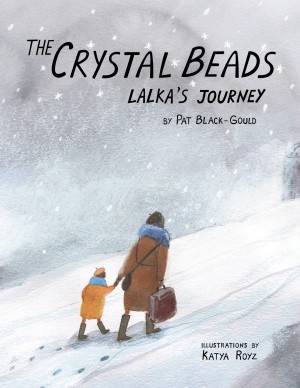

In 1873, progressives in Western Galicia (now Poland) mandated primary education for all children, allowing even the poorest families to afford basic schooling. This also meant that religious families couldn’t avoid sending their children to a state-approved school. Orthodox (here, mostly Hasidic) families only objected to girls learning Torah, so they sent their daughters to the public schools and quietly kept their sons in the cheders. (Indeed, conservative Poles were perfectly happy if Jewish boys didn’t get secular educations, leaving them less likely to compete for Polish jobs.) In school, Jewish girls learned about their Catholic neighbors, learned to speak Polish and were exposed to all sorts of worldly matters. Some of these girls started spending more time with their Polish girlfriends…and then with some Polish boys, too. Or, a girl might decide she really loved schooling, not boys, and beg her parents to let her enter an upper school. Either or both situations might trigger a quick, arranged marriage for the daughter. After the shock of meeting their “betrothed,” some girls took refuge in the nearby Felician Sisters convent and, if they were over fourteen, converted to Christianity. These “lost daughters” became notorious, as their fathers pursued them in the countryside, the courts, and the press.

Manekin details three young womens’ stories. Michalina Araten left her rich, urban Hasidic family and hid away in a variety of convents before leaving Poland altogether. Debora Lewkowicz, a rural tavern owner’s daughter, escaped to a convent and converted, but then semi-renounced her apostasy. Anna Kluger, a gifted scholar, fled home with her sister, not so much to escape her arranged marriage (this husband accepted her academic passion, at least) but to force her parents to pay for her schooling. Barred from any Jewish education, these three women, and so many others, found secular culture infinitely more appealing than the pallid cheder-boys they were promised in marriage. Manekin frames these girls’ struggles within the larger issues facing Orthodox Jewry at the time. Speak Yiddish or German/Polish? Have the rabbi deliver his talk during services (when women might hear it), or at the Shabbos tisch afterwards, which women could not attend? Study Torah “for its own sake,” as they did in yeshivas, or use Rabbi Hirsch’s “Torah in the way of the land” approach, which combined Orthodoxy with an openness to European culture?

So few women are included in Hasidic archives (even Anna Kluger, a direct descendent of the Sandz Hasidic dynasty, appears nowhere in their accounts), that Manekin has done us a great service by uncovering these stories, even appending translations of key documents. A careful historian, she resists telling readers what these girls “were really thinking,” allowing us to draw our own conclusions. Beyond the tales of the runaways, she details how the runaway crisis, and the rise of Jewish gymnasiums for girls, led to the formation of the Beit Yaakov schools for Orthodox girls, with their modest doses of yiddishkeit and secular learning. Contemporary contrasts are inescapable — just as late- nineteenth century Hasidim fought to avoid teaching secular subjects, so the struggle remains alive in the twenty-first century. Who would have thought pre-modern Galicia was so relevant? Brava!

Bettina Berch, author of the recent biography, From Hester Street to Hollywood: The Life and Work of Anzia Yezierska, teaches part-time at the Borough of Manhattan Community College.