Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

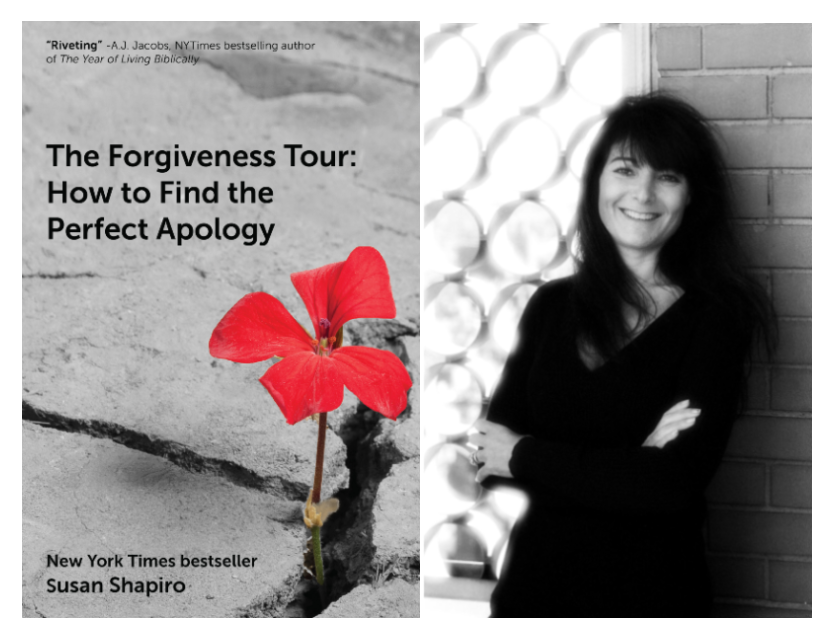

Cover design by Eyal Solomon

Headshot by Dan Brownstein

Best-selling author and award-winning writing professor Susan Shapiro chronicles her journey of betrayal, obsession, and grace in her dark and captivating new memoir, The Forgiveness Tour.

Shapiro has written thirteen books including Five Men Who Broke My Heart, Lighting Up, Unhooked, The Bosnia List and the writing guide The Byline Bible. In the following conversation, she discusses her early influences, culpability, and the Jewish psyche.

Emily Stone: In The Forgiveness Tour, you mention your childhood rabbi talking about atonement on Yom Kippur. Tell me more about your upbringing in Michigan.

Susan Shapiro: I grew up in a conservative Jewish home in West Bloomfield. I loved my parents, three brothers, and friends. Yet like many creative types, I never really fit into normal family life. I was an artistic, overly sensitive black sheep lefty whose essential tenets in life were culled from confessional poetry and Bob Dylan lyrics. Interestingly, my parents were both from the Lower East Side of New York, so I sort of felt switched at birth. The day I moved to Greenwich Village to go to NYU grad school at twenty, I sat in Washington Square Park watching all the weirdos in black clothes chain-smoking and quoting their bad poetry, and I thought: Oh, this is what was wrong with the first twenty years of my life. I was supposed to be here.

ES: What about your spiritual life in New York?

SS: My childhood rabbi, Irwin Groner, used to say that Judaism is a religion, a nationality, and a culture, and that you can embrace only one aspect and still be a good Jew. I’d say I felt very culturally connected. I loved Israel — where I have many beloved relatives. And I gravitated towards Jewish feminists like Gloria Steinem and Ruth Bader Ginsburg; to journalists like Janet Malcolm and Ruth Gruber (who was in my writing group); to fiction luminaries like Isaac Bashevis Singer, Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Amy Bloom, and Etgar Keret; and to poets like Philip Levine, Adrienne Rich, Louise Glück, and Yehuda Amichai, as well as Joseph Brodsky (born Jewish), with whom I studied poetry with at NYU.

ES: Is the concept of forgiveness something ingrained in the Jewish religion?

SS: I think all religions grapple with big universal questions. Based on the wisdom of the spiritual leaders I interviewed, Judaism and Islam seem to consider forgiveness contingent on atonement and repentance more than Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism. I’m very literal-minded and oddly moralistic for a leftwing failed poet, so the Jewish emphasis on asking for forgiveness and granting it made sense to me. As Mahatma Gandhi once said, “An eye for an eye and the whole would be blind.”

ES: In your memoir you seem to question whether forgiveness is related to one’s own culpability?

SS: Most of the religious leaders I spoke with felt that no sin was unpardonable. My family rabbi, Joseph Krakoff, considered a true Jewish apology to be when the person who screwed up finds themself in the same situation again but deals with it differently. That spoke to me, since my whole memoir centers on the questions: Can you forgive someone who doesn’t apologize? Should you? I can forgive anyone anything — if they apologize and stop the hurtful behavior.

My family rabbi, Joseph Krakoff, considered a true Jewish apology to be when the person who screwed up finds themself in the same situation again but deals with it differently.

ES: In your book, you discuss Simon Wiesenthal’s memoir The Sunflower, which famously tackles the question of which sins are unpardonable—it recounts Wiesenthal’s experience as a former concentration camp prisoner who visits a dying Nazi officer and refuses to grant him absolution. When do you think one should not forgive?

SS: In The Forgiveness Tour, I interview a woman who was raped by her father as a teenager. Her misguided counselor pushed her to forgive her father, but then he tried to do it again. I also spoke with Manny Mandel, a close family friend who is a Holocaust survivor who never forgave the Germans and thrived in life out of spite. Cynthia Ozick came out strongly against forgiving the Holocaust, and the Jungian astrologer I quote says that holding a grudge can be smarter and more self-protective. If forgiving someone could put you in danger, I’d say: don’t. Protect yourself and your family first and foremost.

ES: I had a brilliant psychiatrist once who, unbeknownst to me, had Alzheimer’s. Looking back, I can see how some of the things he said and did while treating me were highly suspect. You call your former therapist “the WASP rabbi you confessed to with religious devotion.” Do you regret trusting him?

SS: No, he pretty much saved my life. Because of him I’m a happily married, well published author who has been smoke-free and sober for almost twenty years. Part of the conclusion I came to while writing my memoir was that I could forgive him based on his past help and kindness alone, which I was about to do before he apologized. He has actually inspired four books now, including a New York Times bestseller we coauthored.

ES: Has your relationship to therapy changed?

SS: I don’t see anyone weekly anymore. But I stay open-minded, knowing situations will arise where I’ll need advice or a tune-up. Luckily, I have an amazing husband, astute close friends (some of whom are shrinks!), and loyal writing workshop members on whom I rely for honest feedback and wisdom. When people ask the secret of my sobriety, success, or how I can be such a prolific writer, I always say it’s the ability to seek out and listen carefully to criticism from smart people I trust, and then revise accordingly.

ES: Why do you think so many Jews are in therapy?

SS: Well, Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, was a Viennese Jew. Max Wertheimer, Erik Erikson, Wilhelm Reich, Melanie Klein, Bruno Bettelheim, and Alice Miller were Jewish, too. So was Dr. Joyce Brothers and so is Dr. Ruth. Rabbi Pindrus told me, “The function of the Jewish people is to be a light unto nations. We exist to serve as inspiration, as mentors, guides and educators. God desires that every person maximize their unique potential to reach excellence. But you can’t self-actualize unless your goal is to enable others to.” As I write in the memoir, that sounded surprisingly modern and shrinkadelic for an Orthodox grandfather.

ES: Was Dr. Winters the worst breakup you ever had?

SS: Well, we didn’t really split. We had a six-month conflict that actually had a miraculous ending. I always tell my students that writing is a way to turn your worst experience into the most beautiful. I chronicled my worst breakups in my first memoir, Five Men Who Broke My Heart, which interestingly Dr. Winters helped me publish. So, I’d say it was the best, most productive breakup ever.

Born in New Orleans and raised in Brooklyn, Emily Stone is the author of Did Jew Know? (Chronicle Books).