Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

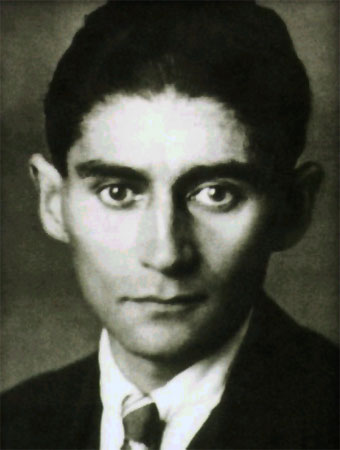

Earlier this week, James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel wrote about a man as puzzling as his stories, Kafka and the parable, and Tamar Yellin’s “Kafka in Bronteland.” Today, Kessel examines the Kafkaesque structure.

One of the influences of Kafka over later writers is not so much in the content of his work as in its form. The conventional Aristotelian plot proceeds by means of a protagonist, an antagonist, and a series of events comprising a rising action, climax and denouement. It involves identification of the reader with the protagonist and vicarious engagement with his or her predicament (even when, as in say,Macbeth, the protagonist is the villain). One event causes the next event, and so on, like a row of falling dominoes. This structure has stood storytellers in good stead for a few thousand years.

One of the influences of Kafka over later writers is not so much in the content of his work as in its form. The conventional Aristotelian plot proceeds by means of a protagonist, an antagonist, and a series of events comprising a rising action, climax and denouement. It involves identification of the reader with the protagonist and vicarious engagement with his or her predicament (even when, as in say,Macbeth, the protagonist is the villain). One event causes the next event, and so on, like a row of falling dominoes. This structure has stood storytellers in good stead for a few thousand years.

But Kafka’s stories do not fall easily into this pattern—The Trial at least seems to begin in this way, though it never fulfills it. Perhaps that is one reason why Kafka had so much difficulty finishing his novels — a novel demands some structure of this type, and Kafka was not able to produce such a structure. In Kafka’s universe, cause and effect are not so sure as other forces.

Rather, what Kafka gives us— and if he is not the originator of it, he brings it to a remarkable perfection— is the story that begins with a premise, often a bald assertion of a fact in contradiction to reality (“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”). The story then progresses not as a series of cause-and-effect links, but as elaboration/qualification/evolution from that assertion. We can see this in “The Great Wall of China,” in “A Hunger Artist,” in the long description of the execution machine that comprises most of “In the Penal Colony,” in “The Burrow.” These stories are not so much narratives as explanations of the world, a world that is fundamentally inexplicable.

Jorge Luis Borges said that Kafka’s stories “presuppose a religious conscience, specifically a Jewish conscience; formal imitation of Kafka in another context would be unintelligible.” But in another time and place, Borges also said that, “I felt that I owed so much to Kafka that I really didn’t need to exist.” Whether or not formal imitation of Kafka was his intent, in fact we can see precisely the Kafkaesque structure put to use in many of Borges’ greatest stories, such as “The Library of Babel,” “The Lottery in Babylon,” “Tlon Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” or “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote.”

Through Borges, Kafka’s influence has spread to several generations of later writers. And it does seem to me that many late modernist and postmodernist stories owe their structure, if not their very existence, to this tradition.

James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel’s anthology, Kafkaesque: Stories Inspired by Franz Kafka, is now available. They have been blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.