Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

The title — and central metaphor — of Israeli cartoonist Rutu Modan’s latest graphic novel, Tunnels, is a captivating one. Humans, and animals, dig tunnels for a variety of reasons: to run away; to forage and explore; to connect places and their inhabitants. In sum, the tunnel is a functional metaphor, both for the limitations of storytelling and for the many bridges that storytelling offers.

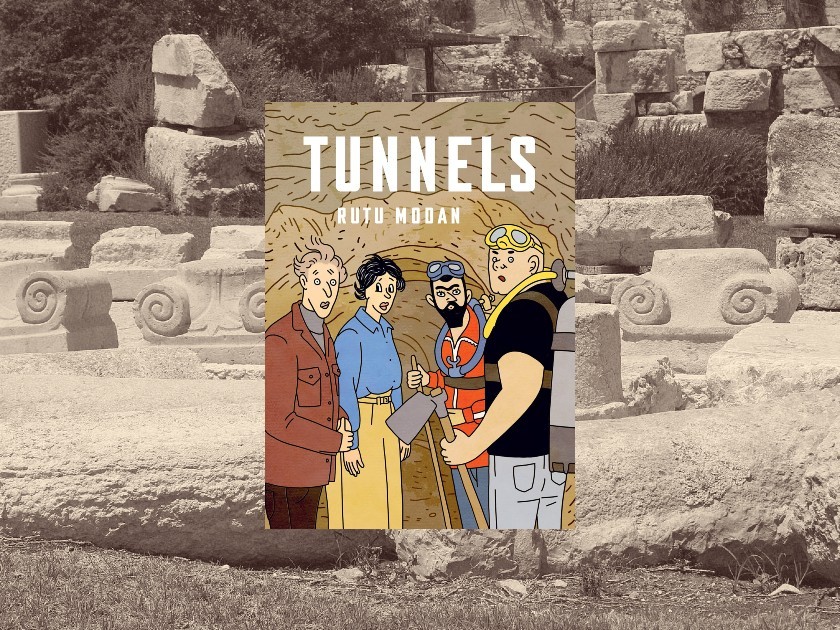

It’s a fitting structural device for a graphic novelist who has had four books translated into English, each detailing the lives of complicated fictional characters, mainly Ashkenazi Israeli Jews. Modan’s last book, the acclaimed The Property published in 2013, is an intergenerational drama starring a granddaughter and grandmother duo on a quest to investigate the past. Tunnels comes almost a decade later, and it’s an impressive work about a group of people invested — each for a different reason — in digging up a lost archeological treasure. In a sense, Tunnels is less a book about individual past lives — though there is the story of a family’s past at its core — and more a meditation on how individuals and groups of people can cling stubbornly to the past, to the detriment of others as well as themselves.

Tahnee Oksman: Tunnels is unlike your other works. Would you begin by explaining where the idea for the book came from?

Rutu Modan: After I published The Property, I rested for a while and then started looking for a new story. I was in a car on my way to the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design where I teach in Jerusalem, and I suddenly remembered something from my twenties when I was a student there. One of my husband’s best friends from high school, who was studying in a different department, had told me a story about when he was young.

He said that when his father was doing his army reserves service, he met a rabbi who told him that he had found a secret code in the Bible, and he knew where the Ark of the Covenant was buried. So his father took him out of school and together they went looking for it — they illegally dug into a mountain near Jerusalem. They actually did exactly what happens in my book. Sometimes, at fourteen years old, this friend even went to dig in the mountain alone, when his father had to go do something else. And my husband, who had been his friend in high school, also went with them a few times.

When we were in the Academy and I heard this story, we laughed about it and that was all. It was just a good story that somebody told me about his father, his family.

Then, in 2013, when I suddenly remembered it, I asked myself, why did they do it? Because they were not religious. And they were just like any other family I knew; more or less, they were a regular family. But now, I wondered, why did they do it? And why didn’t I ask myself about it beforehand?

TO: At its heart, Tunnels is an adventure story with a very specific quest, a daring protagonist, and a number of dangerous obstacles and adversaries along the way. Is that how you think of the book, too?

RM: From the beginning, I thought that the book should be written like a treasure hunt, like Indiana Jones. And that treasure hunt would be like Velcro, and all of the other subjects would stick to it. I think this is also what made the book even more Tintin-like than my other books, in terms of style.

I was never interested in archaeology before, so I thought that now I would have to go and research it a bit. I started reading about Israeli archeology and then I found out that it’s a wonderful subject because it’s connected to so many things that are interesting to me: history, politics. The archeology in Israel is very connected with politics, and also with crime, money, crazy people, obsessions. These are all subjects that I was already interested in.

TO: I can see a lot of themes and motifs in Tunnels also threaded throughout your earlier books. I want to ask you about one in particular: secrecy and secrets, both within and beyond family units. Would you say more about what attracts you to this subject?

RM: In my family — I’m talking about the family that I came from — you didn’t tell others everything, even if it wasn’t important; you just didn’t share everything. This was never said out loud, but this is how it was. I don’t know why. Even my father, when he just went out to the market, he would say he was doing something else.

Now, too, I do some of the same things. These days my life is kind of bourgeois: I have a family, I have kids, I teach, I go to the studio. But I still have to fight myself to answer questions. If I’m going out, either I don’t tell anyone where I’m going, or I have to really fight myself not to lie about it. I don’t know why this is.

And it’s not only from my father’s side of the family. My mother also had many secrets. And you have in the opening [epigraph] of my last book [The Property], my mother’s saying, that in a family you don’t have to tell the whole truth, but that doesn’t mean that you’re lying.

It’s a fact that in my family we have this attitude: something is a secret, and we respect the secret.

TO: The Property is also loosely based on a real-life story, your own family story, isn’t it?

RM: Yes. In The Property, the secret of the character of the grandmother, Regina, is also based on a true story. It’s not exactly the same, but very close to it.

I found out, I think in my late 20s, that my father was an illegitimate child. He was born to my grandmother before she married my grandfather. My grandfather had been married to another woman.

The person who told me this secret was my other grandmother, my mother’s mother. Both sides of my family came to Israel before the Holocaust. And when my parents started dating, one of my maternal grandmother’s friends who knew the family before the war told this secret to my grandmother. My grandmother told it to my mother, but my mother never told it to my father.

I knew, and my sisters knew. But until he died, we didn’t have the courage to ask my father if he knew. I think for ten years, from the moment we found out about it until my father died, we — me and my sisters — we continued to carry the secret. We didn’t ask him about it, we didn’t ask my grandmother about it. Until this day, I don’t know exactly why. It was this secret, and everybody knew about it but nobody spoke of it.

TO: The plots of your books do seem to revolve, more than anything else, around secrets held within families.

RM: It’s a fact that in my family we have this attitude: something is a secret, and we respect the secret.

We are a very close family. It sounds funny to say that because we don’t speak about a lot of things. But I was always very connected to my parents, my uncle, my cousins. It’s why I always write about families; it’s part of my identity. I don’t see myself just as an individual, but always as part of a group, part of a small tribe.

At the same time, everybody in the family is very individualistic by nature. So maybe the secret is like your private thing, something that keeps you safe from the group. You have this spot that you don’t share, and it limits how much the others can interfere in your life.

TO: One of the most interesting relationships in the book is that of Nili and her brother Broshi. I love how complicated they both are. Broshi has this beautiful relationship with his nephew, and he has these moving scenes of caring for his increasingly infirm father. But he also has a disagreeable, more ambitious side. And it’s the same with Nili. Even though outwardly she doesn’t seem as ambitious, when she has her eyes on the quest, it’s like she has these blinders on. She pushes away her son; you see her constant apologies.

It felt like one of the things the book was getting at was this complicated relationship people have between their commitments of caring for others, and their personal or professional ambitions. Is this theme something you felt particularly invested in exploring?

RM: Well, I’m an artist, and a mother, and a woman. So, you know, this is my life.

You have this passion to do something, it’s really important to you, and then you have your family, and you have your kids, and also a husband. And you’re committed to them. This is a life struggle; you never have this problem completely answered.

My mother was a feminist, and I learned feminism from her. Both my parents were scientists, and this was their passion. I grew up knowing in some way that I was not the most important thing to them. They would never say it, but this was how the house was — everything was structured around their work, even family vacations. And as a child, sometimes it was irritating because you want to be the most important thing in your parents’ life.

But I’m the same way. I have this thing that I really want to do, sometimes more than to play with or be with my kids. My kids are grownups now, and now maybe I’m more interested in being with them than they are in me. But when they were kids, I felt guilty. And at the same time, I couldn’t give up. I really wanted to go and do things. When I was in my thirties especially, I just wanted to work all the time. And then I would have to drop everything and go to the kindergarten.

I was lucky that I had my mother because it was like I had the permission to do it. Unfortunately, she died before I became a mother, but she was my model. Even though I was irritated with her sometimes, I was also very proud of her. Because she was so different from other mothers.

Maybe, because of that, it’s been easier for me than for other women — easier in terms of feeling that it’s okay to neglect your family, and have your house be a mess because you want to work.

TO: I want to ask you one more question about the siblings’ relationship. Their present-day rivalry seems rooted in a dynamic from childhood, perhaps stemming from a deep-seated difference in outlook. In one of my favorite moments in the text, they’re standing in front of the dig site talking to each other, Nili says, “The landscape of childhood is the only one you can never really get sick of.” Broshi responds, “Not sure I agree.”

What do you think was at stake for them in this conversation? Is it that some people prefer to idealize their childhoods, while others resist this kind of idealization for a more realistic view?

RM: First of all, I’m glad that you like this exchange. Because it’s just one frame, and sometimes sentences for me are very meaningful, and I wonder if someone will even notice them.

For me, this scene was about Israel, about the land. Israel is not such a beautiful country. Let’s be honest about it. And it has become less and less beautiful because it’s so crowded and everything is so divided. You have this landscape, and they put up a wall. We can speak about the problematic political side of the wall, but it’s also a problem of landscapes. What did they do to you that you put up this ugly thing and divided this small space?

I remember this quote because it is exactly the sentence I said to a friend of mine when we were hiking in Israel. Even in this not-so-beautiful landscape, for me it’s meaningful because I was born and raised here. And she looked at me and said, “I’m not sure I agree with you.”

I tend to be more like Nili in this aspect: I’m always glorifying the past, glorifying my parents. There is an expression in Hebrew, maybe you know it: “You live in a movie.” It’s like someone who doesn’t clearly live in reality but has these fantasies — about life, about the future. “You live in a movie.” My younger sister, she always says to me, “You’re worse than that, even, because you don’t live in a movie, you live in animation.” My younger sister tends to be more realistic. If you have time, I can tell you a small story about it.

TO: I would love to hear a story.

RM: I remember when we were really young. I think my sister was five, so I was nine. I took her from kindergarten and we went home. When we arrived at our block, we saw this spot of red fluid on the ground leading to the house and we found more spots all along the way to the front of the building where we lived.

My younger sister said, “Look, it’s blood.” And I told her, “No, it’s not blood. It’s raspberry juice,” because we always used to drink raspberry juice in our house. I was sure it was raspberry juice, and she said, “No. Don’t you see, it’s blood?” And we argued about it.

And then we went up the stairs and we entered the apartment and my father was covered with blood because he had had an accident. And my mother was cleaning him. This was a very powerful moment. It wasn’t a bad accident, but it was a very frightening image.

This story represents well my sister and I. I always say things are going to be okay and she thinks I’m ignoring reality. And I think she’s always thinking about the bad things.

There is an expression in Hebrew: ‘You live in a movie.’ It’s like someone who doesn’t clearly live in reality but has these fantasies — about life, about the future.

TO: She doesn’t live in a movie.

This makes me think about Nili’s relationship with her father. When the story begins, her father has been sick with some kind of neurodegenerative disorder — I imagine Alzheimer’s — for a long time. And she seems to be in denial about it.

RM: He has Pick’s disease. It’s a kind of dementia, like Alzheimer’s, but it continues for a long time.

TO: It struck me, as I read the book, that she was in denial of the full extent of her father’s illness, and also that she was living her life in a way to avoid confronting it. Did you have a sense, when you were writing that storyline, that you were trying to say something about how people respond to loss and grief?

RM: This is another subject I think that you can find a lot in my books. Grief and loss, losing someone that you love. Partly it’s because I lost my parents at a young age. Not very young, but I was twenty-six when my mother passed away and thirty-six when my father died. They were important people in my life and it was something that influenced me a lot.

I always thought this was maybe the reason I have so much loss in my books. But actually, I started publishing comics in 1990 — before my mother was even sick — and death and family are always there.

There’s another small autobiographical detail about myself that might explain it. As young doctors, my parents lived where they worked. There was a whole neighborhood inside the hospital area that the young staff lived in — nurses, doctors. I grew up in this neighborhood.

I used to visit my mother when she was working in her department, I would go through the internal disease ward and the surgery department. Everything was open. It was also the ’70s. Nobody thought that you had to protect kids, especially doctors. Because for them, it was everyday life.

Even in the time of the Yom Kippur War, in 1973, when I was in second grade. Where we kids played, where we had our playground, the helicopters from the front came in with wounded and dead soldiers — right where we were playing.

Wherever you grow up, you think it’s regular, you don’t think it’s strange. It took me years to understand that maybe this was also something related to the comics I made when I was young, which were all grotesque and full of gore.

TO: The relationship between Nili and her son, whose name is Doctor, was similarly compelling. He is often on any electronic device he can get his hands on — in fact that’s how the book opens — and he’s young, six or seven, and pulled out of school to tag along on his mother’s adventures. I found it amusing how the very thing he is always getting in trouble for — being on an iPhone — is the thing that saves him and his mother.

Would you say a bit about what role you think technology, especially texting, plays in the book? Or more generally, what role do you see technology playing in your life as an artist?

RM: First of all, I don’t have any technophobia. Even though I’m from a generation that grew up before everything was invented, I never had any problems with computers. I think I was one of the first illustrators who started working on a computer in the ’90s. I love technology.

But also, I complain about technology all the time. I’m addicted to it. Instead of reading, I’m going on Facebook or YouTube. And I’m aware of the damage it does — especially for kids.

My daughter is twenty-six and my son is nineteen. There’s a big difference between them because my daughter grew up without an iPhone and good internet. She had a smart phone only when she was already in high school, and the internet was not fast enough to be entertaining. My son was born into technology, and I see the difference. I think that my daughter, it was like she escaped in the last moment.

I’m very aware of the problem, for example, that nobody is bored anymore. I don’t think that animals get bored in nature. And it’s really powerful — I think being bored in the end makes us invent things or think about being creative. And that’s why when my kids were small and said, “Mommy, I’m bored!” I would say, “Oh, good. It’s very good for you.”

Now, there’s no time to be bored. If you’re bored, you immediately have something to entertain you. But it’s not something that you invented. It’s something that somebody else invented. I don’t think it’s good, not to have uneasiness, not to be bored or just let yourself feel empty.

When I was thinking about Doctor, first of all I wanted to show that this is just how kids are. I also wanted to show that Nili loves her son but she isn’t a perfect mother. She’s a single mother and she doesn’t always have patience and also the ability to see what her son wants from life, not just what she wants him to be. She drags him out of school and takes him out on this adventure that he’s not interested in at all. She also wants him to be a genius and have this intuition with archeology, like her father had. She wants him to love what she used to love and have the same adventures.

For her it’s an adventure, but for him it’s not interesting.

TO: I think it’s a beautiful depiction of motherhood.

I don’t want to go too much into the specific politics of the story and what they might symbolize, the messages you could interpret from the key conflicts of the story, the central players in the adventure; in part because you do such a beautiful job of it in your afterword, and in part because I don’t want to give away too many spoilers. And also, it’s so intricate that it would take a long time to explain. But I did notice that your characters often show their ugly prejudices — whether it’s Israeli Jews talking about Palestinians, religious Jews talking about secular Jews, etc.

I wonder if you could talk a bit about those moments of prejudice. Did you have any hesitations about how, or when, to let those slip into the dialogue? What compelled you to show those moments?

RM: For me, this is the most complicated book that I’ve written. It’s also longer than my other books. This is partly because of its subject, politics; it was difficult to find a way to talk about it. Also, there are many characters. It’s not like in my other books, where there are like five characters and the rest are extras. Here there are many characters and each has some kind of arc.

But this is also the first time I wrote about people who are not like me. It’s not only about this Ashkenazi family, or someone from Tel Aviv. There are characters in the book who are maybe supposed to be my “enemies.” And I’m not talking just about Palestinians here but I’m also talking about settlers. In real life, I find it very difficult to understand them sometimes. Why do they talk like this? I’m an artist, I’m from the left — a progressive. But I wanted to understand them, how their minds work.

When I was researching for the book, I interviewed religious people, for example. One of them was a very religious man, but at the same time he’s a doctor. I was talking not to argue with him. And I didn’t want to argue with my characters. I just wanted to present them without judgement — well, I have a little bit of judgement in what I decide to show. But it’s like I am saying of the character, “Okay, you said it. I didn’t say you were a racist, you said it. I’m just quoting you.”

There’s another side of it, too. I have racism in me. I try not to have this racism or prejudice. But I wanted to also look at this in me, in myself. And this is the nice thing about writing fiction. I can put down this thought and look at it and think, maybe I have this thing that I’m fighting, maybe it’s still there. I can put it in somebody else’s mouth, which is not me. And by showing it it’s like saying, it’s there. The fight, the conflict that we have about Palestinians is not just about security and justice, for example. There’s also racism in it. And let’s look at it, let’s face it.

TO: I have been thinking a lot about audience, especially given your interest in writing about secrets and families. Do you think about your audience when you’re working on your books, and does that affect your storytelling?

RM: I don’t think that being a secretive person is in contradiction with being a writer. It’s the opposite. This is why I like to write fiction and not autobiographical work. Then I can tell all of the secrets.

In 2008, I was doing these short pieces for the New York Times website, for a blog called Mixed Emotions. I had to do a story a month, and I decided that I would tell real stories because thinking up stories takes me a lot of time. So I did family stories which were ninety-nine percent true. Since I was living in England at the time and my family was far away, I told myself that they wouldn’t find out about it. Of course my cousin did, and then one of my uncles — someone I had written about. I wrote that he was the black sheep of the family. I changed his name and his profession, but he never forgave me for that.

Now as for the reader, it’s difficult and also dangerous to think about your audience. Before I published Exit Wounds, I didn’t have a very large audience, especially abroad, and I was just doing my thing and I wasn’t really worried about it. I was mainly worried that I wouldn’t have many readers.

But then Exit Wounds was published and succeeded, and I felt the danger. When I wanted to write a new book, I really felt how I wanted it to be loved by the audience as much as Exit Wounds. I felt myself thinking about it while writing, and it was not good.

So I told myself, I can’t think about the audience. I don’t actually know who is going to like it or hate it. My solution to this is that I write for someone I love, a very good friend of mine. His name is Yirmi Pinkus, and he’s a comics artist and a wonderful writer. He has always been my first reader and I’m his. Before we have anything to share, we discuss ideas. When I write, I try to only think about him, what he’s going to say.

TO: You’ve published several books already, which were translated into English via the Montreal-based publisher, Drawn & Quarterly. I wonder if you have any idea about who is most interested in your books?

RM: To say who my audience is, it’s complicated for me because I don’t live near most of them. In Israel, it’s mostly young people because comics is a very new medium to Israelis, even mainstream comics.

With The Property, for the first time suddenly I had a wider audience than just comics readers — because of the subject. People would tell me it was the first comic they had ever read, or their grandmother had ever read, or their mother. Also, sometimes young children read my comics, which is surprising. But then, this is what I love about comics. One kid, eight years old, my friend’s son, he read Tunnels and he was sure that Doctor was the hero. He read everything from Doctor’s perspective, and he was only interested in him.

TO: We didn’t delve too closely into the real-life politics contiguous to your adventure story — the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — but you speak in depth about it in your “Afterword.” I was especially taken by your description of the power storytelling plays in the ways that real life events unfold, and how restricted points of view exacerbate longstanding tensions. You ask a series of related questions: “Are we really that limited that we cannot imagine the conflict coming to an end one day? Can we not, at least in our minds, jump over the tectonic events, still hidden from our eyes, that would lead, three thousand years hence, when the Israeli and Palestinian narratives have been assimilated into one story? …And if we can already imagine such a situation, why can’t we try and avoid the usually unsavory tribulations of history and strive for it already now?”

Do you have anything you’d like to add, in terms of what you were trying to show about the present-day situation?

RM: I don’t mind speaking about the political side but I’m glad you found other subjects to ask me about today. I was a little bit afraid that the book would be framed only around the conflict, but for me it’s not the only subject.

In terms of the politics, I wasn’t trying to look for a solution. I just wanted to say, this is how it is. This is how we’re stuck. This is how I see it.

Tahneer Oksman is a writer, teacher, and scholar. She is the author of “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?”: Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs (Columbia University Press, 2016), and the co-editor of The Comics of Julie Doucet and Gabrielle Bell: A Place Inside Yourself (University Press of Mississippi, 2019), which won the 2020 Comics Studies Society (CSS) Prize for Best Edited Collection. She is also co-editor of a multi-disciplinary Special Issue of Shofar: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, titled “What’s Jewish About Death?” (March 2021). For more of her writing, you can visit tahneeroksman.com.