Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Design by Katherine Messenger

For most of history, Jews rarely traveled for pleasure or edification; they traveled out of necessity. “Travelers are those who go elsewhere because they want to, because they can afford to displace themselves. Immigrants are those who go elsewhere because they have to,” Ruth Behar writes in the introduction to her memoir, Traveling Heavy: A Memoir in between Journeys. Jews — refugees, exiles, stateless — usually fell into the latter category. They often found travel dangerous, as they could never be sure of a positive reception in new places. The trope of the “wandering Jew” — based on a Christian legend about a Jew who rebuffed Jesus on the way to the crucifixion and was condemned to wander the earth until the Second Coming — became the antisemitic lens through which many viewed Jewish migrants. It is unsurprising that until recently, relatively few travel memoirs have been written by Jewish authors.

Those who did have the opportunity to write about their journeys, however, found it an invaluable experience. In “Sharing the Sites: Medieval Jewish Travellers to the Land of Israel,” scholar Elka Weber identifies fourteen full-length travel accounts written by Jews between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. One of the best known, Masa’ot Binyamin (The Voyages of Benjamin) by Spanish merchant and scholar Benjamin of Tudela, details the author’s journey through western Asia, and was written nearly one hundred years before Marco Polo would become famous for completing the same trip. Weber notes that for medieval Jewish memoirists, “travel writing becomes an extended form of self-definition.” By going from the familiar (their home) to the unfamiliar (their destination), they are able to reflect on themselves in relation to what they encounter.

Early female Jewish travel writers are even less common. As Mary Morris notes in an introduction to Maiden Voyages: Writings of Women Travelers, female travel writers were historically “women of the upper classes in European society, invariably white and privileged” (and, we should add, Christian). In Gender, Genre, and Identity in Women’s Travel Writing, Kristi Siegel urges the reader: “Consider … the vast number of women’s journeys that have never been written — journeys of flight, exile, expatriation, homelessness; journeys by women without the means to document their travel; and journeys whose records have been lost or ignored.” The earliest known travelogue by a Jewish woman might be The Memoirs of Glückel of Hameln, penned by a German businesswoman who lived from 1646 to 1724. As Stephanie Slyverne notes in an article for Kveller, “Glückel traveled frequently to conduct business … risking pirates, thieves, and lands where simply being Jewish was dangerous in itself.” Her memoirs, written in Yiddish, were meant to be read by her family, but were eventually published in 1896. However, Glückel was an exception. If there were other eighteenth- or nineteenth-century Jewish female writers, they have been lost to history. In Journeys Beyond the Pale: Yiddish Travel Writing in the Modern World, Leah Garrett writes that one of her objectives is to move “beyond the Wandering Jew and to have the Yiddish writers speak for themselves.” Significantly, though, she notes that she does not discuss any works by female writers, because she could “find no appropriate works by women writers to include.”

The earliest known travelogue by a Jewish woman might be The Memoirs of Glückel of Hameln, penned by a German businesswoman who lived from 1646 to 1724.

But in the last few decades, the number of travel memoirs by Jewish women has bloomed. Many of these accounts either center on the Jewish past of a place, or describe places where there is no Jewish past to reckon with. Unease permeates this body of work; some writers experience it primarily as Jews, others mainly as women. In both cases, however, unease often ultimately leads to self-realization and empowerment. Like their medieval male predecessors, contemporary Jewish women use travel writing as an “extended form of self-definition,” constructing ideas about their own identity vis-à-vis the locations they describe.

“We leave behind the creature comforts and familiarity of home in order to explore alternate worlds, alternate selves,” Ruth Behar writes in Traveling Heavy. A Cuban Jew, Behar immigrated to the United States when she was five years old. Her memoir dives into her family history — her Ashkenazi maternal grandparents, and her Sephardic paternal grandparents. Behar grows up confident in her religion, steeped in its history and traditions. However, when she travels to Poland and Spain — countries from which her ancestors came — her relationship to her Jewish identity shifts. While doing fieldwork as a cultural anthropologist in Spain, she feels she must hide her religion: “I felt uneasy announcing I was a Jew, let alone a Jew with roots tainted by the expulsion.” To blend in, she attends mass, makes the sign of the cross, and doesn’t correct others when they assume she is Catholic.

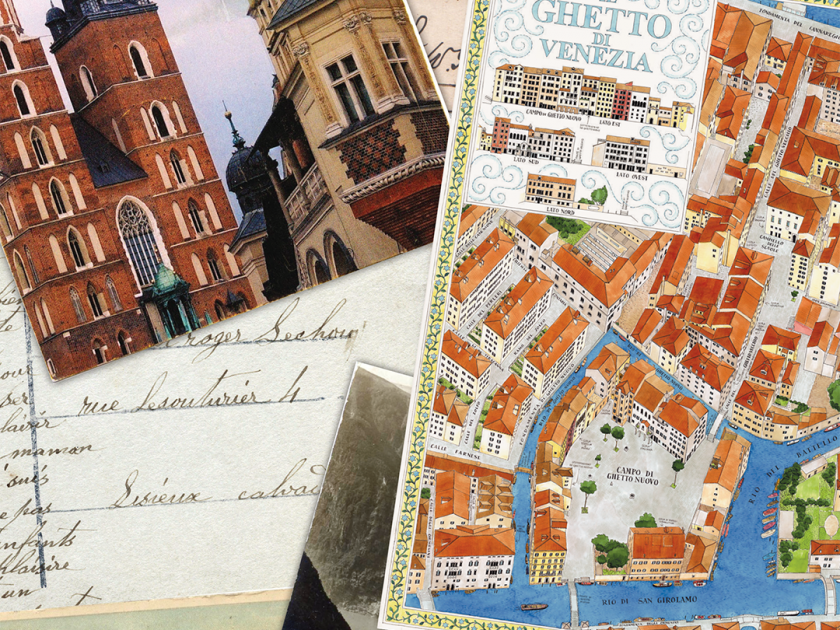

Despite her attempts to conform, Behar yearns for a “sense of belonging” in Spain, and goes on a Jewish heritage trip to try to find where her family once lived. On this trip, she notices the ways in which “fake markers of Jewish memory” are imposed on places where Jews once lived. In the city of Hervas, where all traces of a Jewish past were erased, the tourism bureau has built a “Jewish tavern,” put up street signs in Hebrew, and more. For Behar, it rings false, “Disneyfied.” This feeling is echoed in other Jewish heritage travel writing. In “Righteous Gentile,” an essay originally published in Harvard Review and reprinted in Best American Travel Writing 2018, Eileen Pollack describes encountering a similar phenomenon on a trip to Poland with her Polish Catholic boyfriend to visit his relatives. Pollack’s own grandparents fled the country, and when she and her boyfriend visit the Jewish quarter in Krakow, she finds it “creepily devoid of Jews.” At the same time, she notices that “Judaism has become trendy” in Poland; “Poles who once would have cursed you for intimating they had a drop of Jewish blood now go to great lengths to claim their Jewish ancestry.” Although Pollack, unlike Behar, has not traveled with the goal of excavating her family history, she still reacts as a Jew in a country that has murdered its Jewish population.

At the same time, she notices that “Judaism has become trendy” in Poland; “Poles who once would have cursed you for intimating they had a drop of Jewish blood now go to great lengths to claim their Jewish ancestry.”

The inevitability of confronting Jewish history is also a theme in Rebecca Schuman’s Schadenfreude, A Love Story: Me, the Germans, and 20 Years of Attempted Transformations, Unfortunate Miscommunications, and Humiliating Situations That Only They Have Words For. Schuman, a “nonpracticing half-Jew from Oregon,” writes about her (mis-)adventures in Germany. Her initial interest in learning German has nothing to do with the Holocaust; she simply wants to read Franz Kafka (her literary idol) in the original. Her German studies lead to a homestay after her freshman year of college in a small village outside Münster, during which she asks the daughters in her homestay family if they have ever even met a Jewish person. “Nur dich,” one responds. “Just you.” Schuman responds with her “best loaded look,” telling the reader: “I may have committed my share of minor infractions in their house, but fuck if I wasn’t going to remind them that they were almost certainly the direct descendants of people who had either passively or actively participated in the genocide of the tribe with which I selectively identified when, for example, reminding them of their cultural debt to my people made my behavior as a houseguest appear briefly above reproach.” Schuman uses tongue-in-cheek humor to gently mock her younger self, but her comments about the Holocaust — which on the surface seem to be a deflection of guilt for being a bad guest and feeling misunderstood by her host family — also reflect real disquiet as a Jew in modern Germany.

In traveling to countries with a Jewish past — in some cases linked to their own family’s past — Behar, Pollack, and Schuman are unnerved to find places “devoid of Jews,” and either antisemitic prejudices or philosemitic reconstructions of Jewish heritage. But it is this very discomfort that pushes them to self-discovery.

Other contemporary Jewish travel writers place female rather than Jewish identity in the foreground of their work. In Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London, Lauren Elkin recounts traveling to Venice in search of a hidden synagogue that will serve as the setting for a key plot point in a novel she’s writing. One Saturday, she tries to attend Shabbat services, but the guard initially doesn’t allow her into the synagogue because she’s carrying a camera and cell phone. “The word ‘ghetto’ originates with the Jews in Venice,” Elkin writes. “Still, here’s me trying to get into the ghetto of religious identification. Why am I so anxious to be bound to someone else’s rules?” While not as explicit as in the other memoirs discussed, the Jewish past — the ghosts of Jewish Venice, and of the ghetto — bubbles under the surface.

Some Jewish women write about getting as far away from family history as possible, diving into the unknown. It’s not the past that makes them uncomfortable in these places, but their own presence, today, as Jewish women. In her memoir, I Might Regret This: Essays, Drawings, Vulnerabilities and Other Stuff, Abbi Jacobson documents her road trip from New York to California she took after a breakup. As she eats alone at a bed-and-breakfast, she deals with her anxiety surrounding the societal narrative of the solo female traveler. “A young-ish single woman alone is seen as inherently pathetic — instead of incredibly empowering. A man on the same road trip would be viewed as a cool loner, figuring himself out as he explored the vast roads of our beautiful country. There are no projections about the men, no questions, no pity.” The feeling of being judged at the bed-and-breakfast as a single, female traveler prompts Jacobson to analyze her own insecurities (leading to a particularly humorous anecdote about hiding weed in the box that held the Kiddush cup she was given at her bat mitzvah). Even when she is feeling her most vulnerable, Jacobson asserts the ability to self-reflect and self-define.

Some Jewish women write about getting as far away from family history as possible, diving into the unknown. It’s not the past that makes them uncomfortable in these places, but their own presence, today, as Jewish women.

In her memoir, Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube: Chasing Fear and Finding Home in the Great White North, Blair Braverman details her time in Alaska and Norway.The bookfocuses on Braverman’s travels as a woman in the outdoors, and the specific gendered violence she faces, but it also addresses her identity as a Jew. Like Jacobson, Braverman travels to places where there are few, if any, Jewish people. While she is living in northern Norway, she is asked to lead “Ask-a-Jew” sessions at the local middle school, because most students and teachers “had never seen a Jew before.” In an interview for Alma, Braverman explains that it is important to her to be visibly Jewish. “It’s dangerous, I think, for people to think they’ve never met certain kinds of people,” she says. “Like if you think you don’t know any queer folks, or immigrants, or Jews — that’s how groups of individual humans are reduced to symbols and ideas. If I know someone, if I’ve lived with them, I don’t want them to be able to tell themselves that they’ve never met a Jew.” This is why Braverman is open about her religion — even if, in doing so, she marks herself as “other.”

By placing herself in a foreign environment, the writer turns inward to address her uneasiness and discomfort, and emerges with a better understanding of herself. Even if the authors discussed here are vulnerable during the journey itself, writing about it is a way to process and claim the experience. Whether they’re returning to where their ancestors once lived, like Ruth Behar, or traveling to where few Jews have lived, like Blair Braverman, these writers find empowerment in displacement.

Emily Burack is a writer and editor based in New York. She’s currently an associate editor at 70 Faces Media.