Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

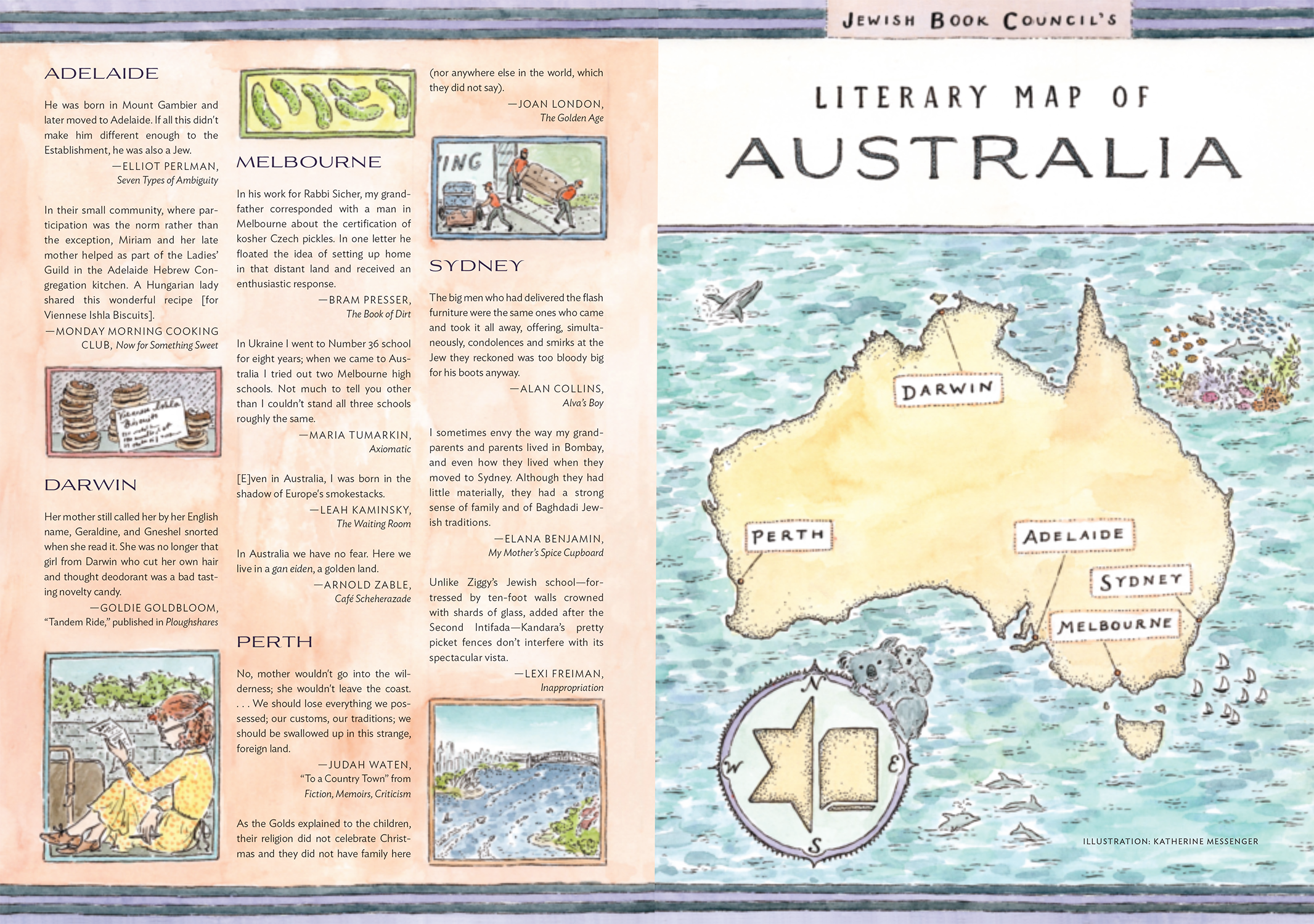

Click here to view the larger image. Illustration by Katherine Messenger

There was a time when emigrating from Europe to Australia felt like sailing to the area on a map marked, “Here be dragons.” The first white settlers landed in Botany Bay in 1788. Among them was my fourth-great-grandfather, who was transported there because of his role in the Pentrich Revolution. Of the 751 convicts who were sent from England to Australia on the First Fleet, sixteen were Jews.

The loss of connection with family and homeland was almost absolute. This was in an age before cell phones and computers made the world smaller. This was even before the existence of a reliable postal service, or cables underneath nine thousand miles of ocean that could bring the voices of your loved ones — at great cost and with terrible sound quality — to your telephone. After being transported, my fourth-great-grandfather wrote to his wife: “Forget I ever existed. It is as if I have died. I no longer am a person.”

Australia continued to feel unfathomably distant for many European Jews well into the twentieth century. Few Jews applied for Australian passports even when they were desperate to flee the Nazis. My American friend’s parents, who wanted to escape Hungary in 1944, were first offered visas for Australia, but they ultimately chose to wait for permission to enter a country with a larger Jewish population. To them, moving to Australia seemed like trading one certain death (at Auschwitz) for another (on a vast, unknown island where there might not even be any other Jews).

In the late 1930s, the Freeland League proposed an area of Australia as the new Jewish homeland. Despite the initial support of the Australian government and clergy, the delight and financial support of Joseph Stalin, and the Durack family’s offer of a million acres of land, the plan never took off. By the end of World War II, Australians were reluctant to accept the men and women who had survived the atrocities of the Holocaust. Nevertheless, there was a small but steady stream of Jewish immigrants after the war. In 233 years, the Jewish population of Australia grew from those sixteen original convicts to over 100,000 people today.

Pulling up roots and replanting them in the hot, red dirt of Australia is central to Jewish identity in the Antipodes.

In reading books and stories about the Australian Jewish experience, I am struck by how many are migration narratives. Pulling up roots and replanting them in the hot, red dirt of Australia is central to Jewish identity in the Antipodes; we are all migrants or descendants of migrants, trying to adjust to a new climate, culture, and language. Some authors describe this transition as jarring. In his short story “To a Country Town,” the twentieth-century Australian writer Judah Waten expresses the fear of many immigrants: “We should lose everything we possessed; our customs, our traditions; we should be swallowed up in this strange, foreign land.” In her novel The Golden Age, Joan London describes the isolation of the Gold family, who have escaped the Holocaust in Hungary but “did not have family” in Australia “nor anywhere else in the world.” And in The Dangerous Bride, Lee Kofman writes that “[b]eing a Jew meant that you never felt secure anywhere, not even in the Antipodean haven.”

And yet, there are other sides to the immigrant experience as well. When I was about twelve years old, I complained about the heat one day in shul. Jeannie Baumwohl, an Auschwitz survivor originally from Krakow, patted my hand and said, “You don’t even know how lucky you are to live in this country. Never complain! Let everyone see how grateful you are just to be alive.” This gratitude for Australia as an adopted home is reflected in literature. In Bram Presser’s novel The Book of Dirt, a survivor in Prague is eager to start over in Australia, “that distant land.” In Arnold Zable’s Cafe Scheherazade, a survivor declares: “In Australia we have no fear. Here we live in a gan eiden, a golden land.”

Other writers add even more facets to the narrative. Some tell Sephardic or Mizrahi immigrant stories — such as Elana Benjamin, who traces her family’s journey from India, Iraq, and Burma to Australia in her memoir, My Mother’s Spice Cupboard. And for authors like Lexi Freiman — who writes about a Jewish misfit at a Sydney boarding school in her novel, Inappropriation—the immigrant experience is no longer the defining element of the Jewish Australian one.

Jews, who form one of the smallest minority groups in Australia, are far from the only people to feel lost or alone there. The pain of being othered is widely represented in Australian literature — in writing by the earliest English, Irish, and Scottish immigrants; by the later waves of Greeks and Italians, and Vietnamese, Indians, and other Asians; by Indigenous Australians. Each has their own struggle to find a voice. American author Claire Messud, referring to her move to Australia in her early years, writes, “We let fall the North American trappings as efficiently as we had let go of our little red car, and we learned not to look back, and not to look forward, but instead to read the present.”

Read the map in print in the 2022 issue of Paper Brigade.

Goldie Goldbloom’s first novel, The Paperbark Shoe, won the AWP Prize and is an NEA Big Reads selection. She was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and has been the recipient of multiple grants and awards including fellowships from Warren Wilson, Northwestern University, the Brown Foundation, the City of Chicago, and the Elizabeth George Foundation. She is chassidic and the mother of eight children.