Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

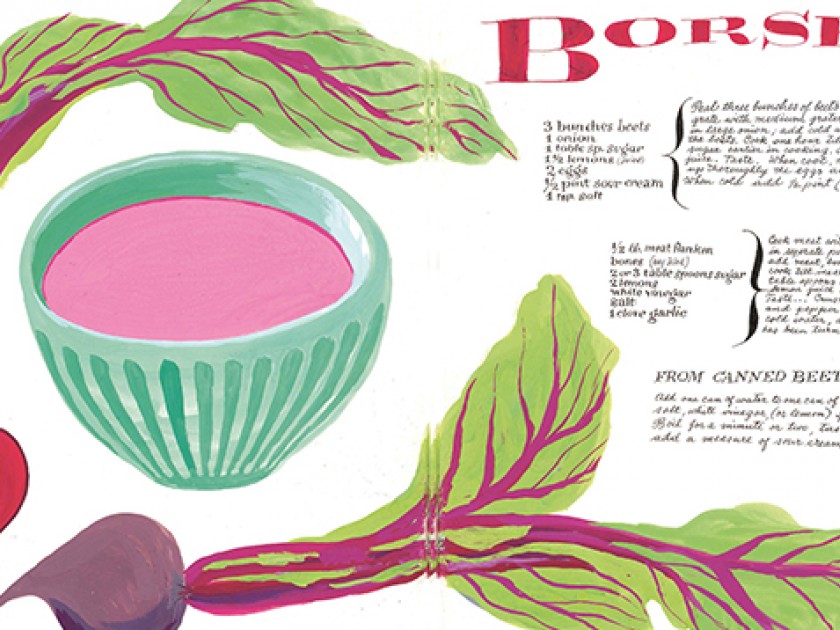

Illustration and recipe by Cipe Pineles

Sarah Rich is the co-editor of Leave Me Alone with the Recipes: The Life, Art, and Cookbook of Cipe Pineles. Cipe (pronounced “C. P.”) was one of the most influential graphic designers of the twentieth century, and the first female art director at Condé Nast.

When I first flipped through Cipe Pineles’s hand-painted recipe book from 1945, it felt deeply familiar. This was my family’s food — not the food we ate for dinner on an average evening during my childhood, but the food we kept in our cultural pantry.

It was a wonder to see these dishes rendered with so much vibrancy and character in Cipe’s art. In my mind, many Eastern European Jewish foods were fairly plain and monotone. You could paint matzo balls, gefilte fish, potato latkes, noodle kugel, kasha and brisket all within a spectrum from beige to brown. Yet here was a rainbow of beets, carrots, peppers, and tomatoes; not to mention the cool blue enamel and warm clay of the cookware. It was a visual celebration of a cuisine that typically feels nostalgic, comforting, old.

Cipe’s paintings, too, were old by the time we found them — almost seventy years old — but the food felt alive, the aesthetic very current. I remember thinking, Why can’t this food feel contemporary and dynamic? Jewish deli foods were coming back into vogue. Places like Mile End Deli and the reinvigorated Russ & Daughters were New York City destinations, while Wexler’s and Wise Sons were served “appetizing” on the west coast. I figured it must be possible to go beyond deli fare and give a modern update to some deeply Jewish classics.

There were a few challenges to doing this. For starters, the recipes as Cipe had written them did not always hold up as a set of specific instructions. It would take an experienced home cook to read through her writing and know where to adjust and improvise in order to arrive at a tasty result. When I first tried her kalacha (aka meatloaf), for example, I followed her recipe to the letter, and ended up with more of a sauce than something sliceable.

The second challenge was deciding where the line was between modernizing a dish, and fundamentally changing it. What makes these dishes what they are? If you took “hard rolls” and chicken fat from her veal stuffing, and instead used breadcrumbs and butter, would it still contain the DNA of the original? And what if instead of veal, you used steak? The politics of animal rights and emphasis on seasonality that characterize today’s food choices just weren’t factored into recipes in 1945.

To develop the updated versions, I worked with an assistant, Christian Reynoso, who cooks at the famed San Francisco restaurant, Zuni Café. He did not have a background in Jewish food. He did have a deep familiarity and great proficiency with the ingredients of the moment in California cuisine. Together we waded around the grey area in between old world and new, and aimed to make something that would tempt today’s cooks and eaters.

For many of the original recipes, it’s possible to skip the first few steps by virtue of what’s available now in grocery stores. Cipe’s soup recipes often start by making a stock, then removing the flavoring materials, whether vegetable or meat, and moving on to the actual dish. For the new recipes, I provided two basic stock recipes — one vegetable and one chicken — as a foundation for the entire collection, with the idea that if you have this (or pre-made stock from the store) on hand, you’re already several steps into the recipe when you start.

The updates vary in how far they divert from Cipe’s originals. The chicken soup I felt was a revelation almost just as she’d written it. I had never heard of putting a short rib bone (what was called flanken) into a chicken soup but I will never do it another way henceforth.

In the middle ground was the bulbenick, a baked potato casserole of sorts for which Cipe had two variations. As written, it really didn’t turn out too well with either variation, so we developed our own, still using the bare bones of her recipe (grated potato, flour, egg), but leavening it gently with baking powder and throwing in herbs for added dimension.

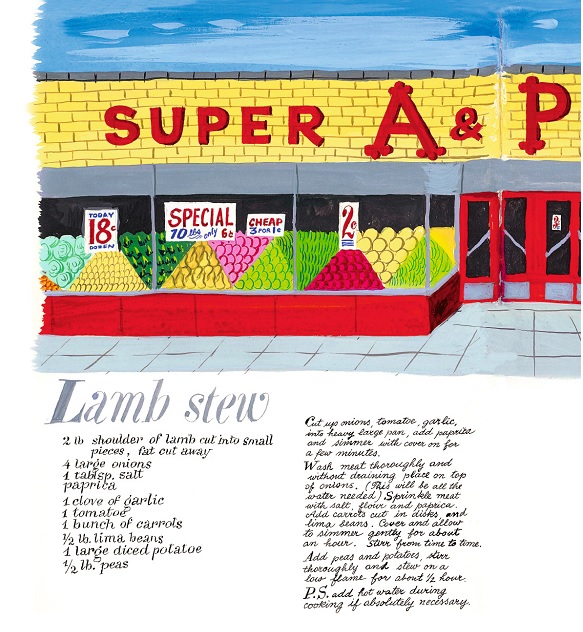

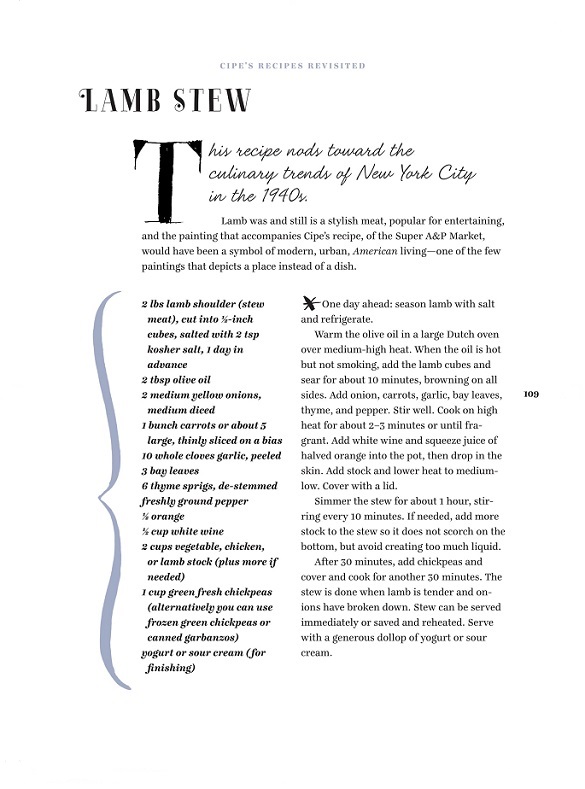

Finally, one of the updates that departs most dramatically from the original is probably the lamb stew. Certain practices common to today’s cooking, like seasoning meat a day ahead and browning it before simmering, were absent in Cipe’s recipe. We felt the flavor and texture turn out much better using these modern approaches, so we changed up the order of operations, added a few steps, and then finished it off with garbanzo beans and yogurt — two ingredients that often pair with lamb in Middle Eastern cookery.

It was a real creative adventure to develop these updates, and an interesting exercise to think through what are the defining and fundamental aspects of a dish. In the end, I’m glad we were able to publish both the unaltered originals and the modernized collection, so that readers can pick and choose, compare and contrast, and draw their own conclusions about what makes a recipe a recipe.

Below, see Cipe’s recipe for lamb stew followed by Sarah’s updated recipe.

Illustration and recipe by Cipe Pineles

Sarah Rich is a writer based in Oakland, California. She is the co-editor of Leave Me Alone with the Recipes: The Life, Art, and Cookbook of Cipe Pineles. She is a former editor at Dwell, Smithsonian, and Medium; and co-founder of Longshot Magazine and the Foodprint Project.