Anders Rydell is the author of The Book Thieves: The Nazi Looting of Europe’s Libraries and the Race to Return a Literary Inheritance. We couldn’t resist drawing readers’ attention to the Paper Brigade of the Vilna Ghetto, for which Jewish Book Council’s annual print journal is named! Anders will be guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

I arrived in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, for the first time on a burning hot day in August 2015. I had expected, perhaps prejudicially, something gray and gloomy — how we in the West typically picture Eastern Europe. Instead I met a city buzzing with life, with coffee shops full of hipsters, vegetarian restaurants, and young people. The city was beautiful, almost picturesque, with old stone houses from the nineteenth century. Much of the older parts of Vilnius had been saved during the War and the city was therefore spared the concrete architecture of the Soviet era. I walked around in the crooked medieval streets of the old Jewish neighborhood, where Yiddish words on the walls and above the entrances can still be seen from the street.

It was beautiful, to be sure, but there was something very sad about this part of the town. The houses had been saved, but not the soul of Vilnius. It was the same feeling of walking in the ruins of Pompeii.

It was no coincidence that the YIVO (Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut) headquarters were established here before the Second World War. The institute was founded around a mission to both save and develop the Yiddish culture and language. Hundreds of researchers collected manuscripts and books and documented songs and folk tales. They soon built one of the most important collections of Yiddish culture in the world, boasting highly influential board members like Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud.

Vilnius was the true heart of the European Yiddish culture in its time. This was a city known the world over for its libraries, intellectuals, poets and rabbis like Elijah ben Solomon Zalman. When this city and its large Jewish community were swept away by the cataclysmic event we call the Holocaust, or the Shoah, Yiddish culture never really recovered.

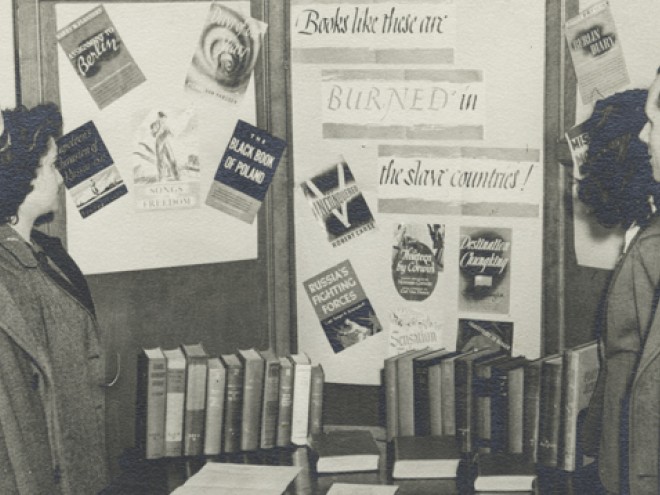

When the Nazis conquered Vilnius, in the early days of the Barbarossa invasion, they found an immense amount of intellectual treasure — libraries, archives, and other collections amassed by generations of Jews and ethnic Lithuanians. In the history of the Second World War, we rarely talk about the importance of Vilnius compared to cities like Leningrad and Stalingrad. But for Nazi intellectuals like Heinrich Himmler, Alfred Rosenberg, and Joseph Goebbels, Vilnius was extremely important. The city was not a military center, it had no important fortifications, but here the walls and resistance were built on ideas and culture. Vilnius was perceived as a center for Jewish intellectualism: in the Nazi war of ideas and ideology, this city was one of the most dangerous in the world.

The Nazi’s immediate steps to break the spirit of Vilnius were to target the city’s books and scholars. The looting of books and archives had two main purposes: to take away the weapons — that is, books — of the intellectuals, and to build a foundation of Nazi research on the plundered collections. Only by also conquering the words of their enemies could the Nazis ensure that they would also control history. When you “own” the libraries and archives, the written memory of your enemies, you have the power to control their history.

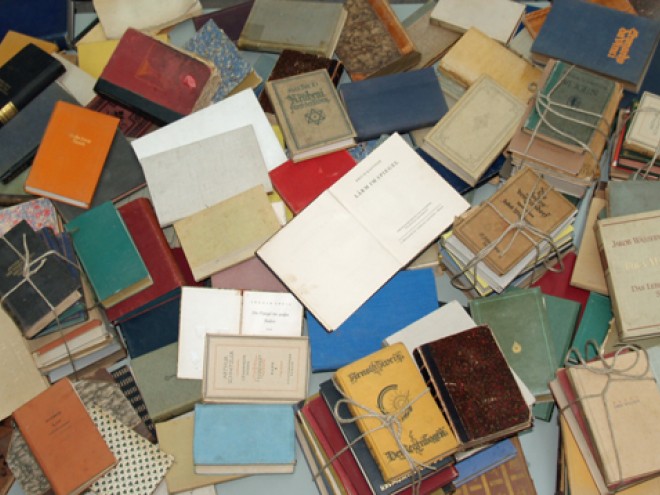

But the Nazi looters had a problem: they stole more than they could handle. The Nazis did not have enough “Jewish experts” that could read Yiddish and Hebrew, therefore they could not identify or sift out the most important or precious works.

The solution to this problem was typical for the Nazi regime: they let their victims do the job. The Nazis formed slave labor groups of academics, writers, poets and librarians; the very same people who had recently built, studied, and protected these collections were now assigned the horrific task of sorting and packing them for the Germans. For members of this group, like the poet Andrew K and Herman Kruk, it was a quintessential Catch-22: if they did not carry out this work it could cost them their lives, and important collections could be lost forever, owing to the Nazi researchers’ incompetence; if the Jewish prisoners did the work, there was at least a chance that both they and the collections could survive — if the Nazis lost the war. But the horrific truth was that the purpose of this work was to destroy the Jewish people and their culture.

The members of the sorting team did their best to slow down their work, to win time, without making the Germans suspicious. But for some members, like the poet Andrew Sutzkever, there was only one moral solution to their dilemma: resistance. The resistance of librarians and collectors.

Sutzkever and his comrades started hide and smuggle out important manuscripts and books. The group soon became known in the ghetto as the Paper Brigade. As other Jews in the ghetto tried to hide potatoes or loaves of bread for their survival, the members of the sorting party risked their lives to smuggle letters and diaries. Even if they only succeeded in saving a very small portion of the archives, their resistance was the work of true heroes.

Only a handful of the members in the Paper Brigade survived World War II, but among those who escaped was Suztkever, who joined the Jewish armed resistance to assist in the liberation of Vilnius in 1944. Returning to the remains of the Vilna Ghetto, Suztkever succeeded in retrieving some of the hidden books and manuscripts. Suztkever continued in his efforts to preserve Yiddish culture even after the war, writing and circulating contemporary poetry that embodied Judaism’s rich literary heritage.

Anders Rydellis a journalist, editor, and author of nonfiction. As the Head of Culture at a major Swedish media group, Rydell directs the coverage of arts and culture in 14 newspapers. His two books on the Nazis, The Book Theives and The Looters, have been translated into 16 languages. The Book Thieves is his first work published in English.