Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

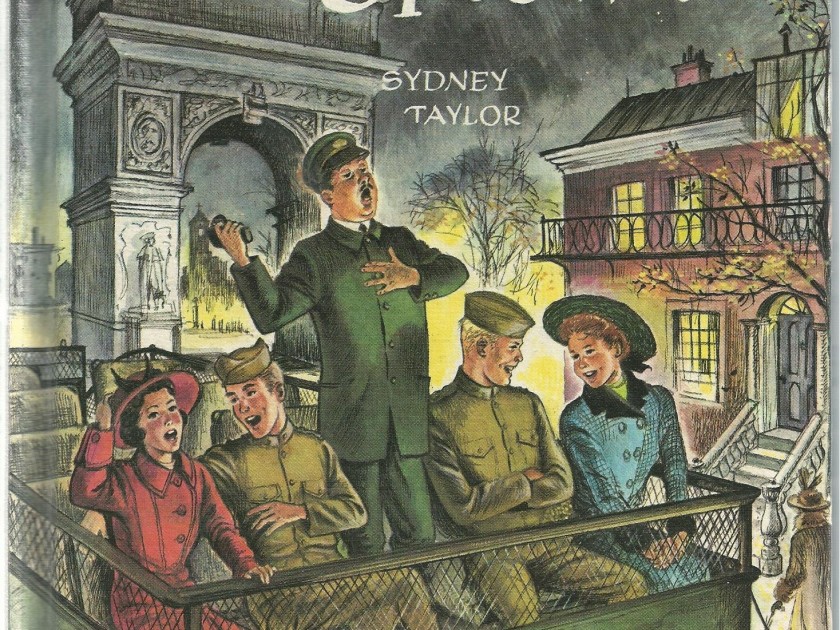

All-of-a-Kind Family Uptown, by Sydney Taylor

The holiday of Shavuot has several faces, each representing a profoundly important aspect of Jewish history and religious practice. One of the three pilgrimage festivals — along with Passover and Sukkos which required observance at the Temple in Jerusalem in ancient times — its origins were agricultural; seven weeks after Passover, Israelites brought the first fruits of their harvest as an offering to God. Shavuot is the time when Jews celebrate the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai, and is also indelibly associated with reading the biblical Book of Ruth. Although all of these aspects are both historically and theologically related, authors and illustrators of children’s books have often chosen to highlight one of them in presenting the complex riches of the Feast of Weeks. However, there is another Shavuot tradition, that of decorating synagogues and homes with beautiful adornments, both natural and handmade. Sydney Taylor and Sadie Rose Weilerstein are two authors who responded to the challenge of Shavuot by integrating this theme of artistic creativity into their stories, focusing on the lives of gifted young women. In Taylor’s All-of-a-Kind Family Uptown and Weilerstein’s Ten and a Kid, female characters participate in religious experiences through aesthetic projects, both performative and visual, rooted in the lives of their communities.

Ella, the oldest sibling in Taylor’s series, directs her synagogue’s Shavuot play, combining her theatrical talents and enjoying authority while giving meaning to her own life at a difficult time. In Weilerstein’s novel set in an Eastern European shtetl, twelve-year-old Fayge is a preternaturally gifted artist who fulfills her personal vision and enjoys the accolades of her neighbors by crafting a stunning ritual object. In both novels, observance of Shavuot provides women the opportunity to reach out to their communities and look within as successful artists immersed in Jewish life.

Sydney Taylor (1904−1978) was herself an aspiring actress as well as a performer with the Martha Graham Dance Company, before dedicating herself to marriage, family, and a career as an author. Her character, Ella, also loves to perform. (Consistent with the values of the author’s time, in the final book in the series, Ella of All-of-a-Kind Family, Ella ultimately gives up professional acting for the sake of her future family.) In All-of-a-Kind Family Uptown, illustrated by Mary Stevens(1958), Ella’s upwardly mobile family has moved from the Lower East Side to the Bronx, and the United States is involved in World War I. The chapter “Play for Shavuos” opens not with a description of the Jewish holiday, but with a patriotic response to the nation’s crisis (both books use the Ashkenazi spelling of the holiday). The synagogue’s Shavuot play, to be directed by Ella, is introduced as a fundraiser for the Red Cross. One of the underlying themes of this post-World War I series is Jewish-American civic pride, and full acceptance of Jews by their gentile neighbors.

One of the underlying themes of this post-World War I series is Jewish-American civic pride, and full acceptance of Jews by their gentile neighbors.

But the play has another purpose for Ella. She is anxious about her boyfriend Jules, a soldier who is off fighting in Europe. Directing the Shavuot play will be a chance to turn her worries to a productive purpose. Ella’s mother reminds her that “…there’s nothing like work to help you forget trouble,” and soon Ella is fully committed to the play. Taylor describes Ella’s consuming involvement and her unmatched skills. “Ella’s guiding hand was in everything.” While other teachers sewed the costumes, it was Ella who designed them. On the other hand, while male students assemble scenery under her supervision, Ella herself does much of the painting, reluctant to surrender control to someone less able. The results are incredibly lifelike; the “golden fields filled with cut sheaves seemed so real that one could almost smell the fallen gleanings.” Even when Ella’s sister, Henny, takes charge of choreography, Ella intercedes with suggestions. When she realizes that the girl playing the biblical Ruth cannot sing, at least according to her standards, Ella devises a plan to avoid compromising her exacting ideals. At this point in the narrative, it seems that the primary goal of the Shavuot play is to showcase Ella’s broad range of talents.

Then the show begins, and Taylor inserts the biblical story into the text. A child’s narration tells a simplified version of Ruth and Naomi’s story, both teaching and fascinating the public. Ella is teaching Torah to her community, as well as extending a bridge to her non-Jewish neighbors in the audience. When the moment comes for Ruth to sing a solo based on the biblical text, Ella’s voice emerges while the actress merely mouths the words to the song. Ella’s need to exert total control over her production seems to contradict the supporting role to which women were limited in the early twentieth century. The poor girl playing Ruth, who is not named in the story as if in deference to her feelings, is reduced to a mouthpiece for Ella’s superior voice. In another incident threatening the play’s cohesion, Ella’s youngest sister, Gertie, suffers embarrassment while performing a dance sequence. Her skirt becomes unpinned, and she is the object of mocking laughter. Ella, in a mix of maternal reassurance and insistent perfectionism, encourages her sister to return to the stage and literally pushes her out of the wings.

After the play, the family returns home to enjoy traditional dairy blintzes and to kvell over the one hundred and twenty-five dollars raised for the Red Cross. Ella’s theatrical triumph has benefited her community and her country but was also a vehicle for her energy and talent. In a somewhat ambiguous conclusion, Ella asserts that it was her father’s unintentional diminishing of her project that had motivated her. When she first noted that the actress playing Ruth could not sing, he had remarked, “Ten years from now, who’ll remember who sang?” giving Ella the idea to substitute her own voice for the girl’s. Was Ella willing to risk failure if the scheme did not work because, as her father pointed out, the whole event was transient and easily forgotten? This seems unlikely. Her narrative perspective dominates the chapter, calling the reader’s attention to her accomplishments: “Murmurs of admiration swelled…from the auditorium…The audience applauded loudly…Everyone agreed that it had been a huge success.” The Shavuot play was not likely to fade from the collective memory, or from Ella’s.

The Shavuot play was not likely to fade from the collective memory, or from Ella’s.

Fayge, in Sadie Rose Weilerstein’s (1894−1993) Ten and a Kid, illustrated by Janina Domanska (1961), is also a creative spirit, although her introverted nature and quiet spirituality set her apart from Ella’s very public presence. Religious observance is central to her large family and their community, but she and each one of her seven siblings are individuals with distinct ways of expressing their personalities. While her sister is an eloquent feminist who insists on learning Torah and fulfilling other mitzvot usually denied to women, Fayge is most focused on artistic expression of her relationship to God. The author states, that “Fayge had always been different from the rest of the children.” Where others see only what is before their eyes, Fayge sees beyond that. Her favorite holidays are Sukkos and Shavuot, specifically because of their association with physical transformation. Fayge sees the green boughs and grasses that beautify her home on Shavuot as analogous to a poor girl being dressed like a princess.

The chapter “Fayge’s Tree” weaves together the natural and artistic creations, which, for Fayge, embody the festival. When a neighbor gives her a small tree to plant in her own yard, she lovingly waters it and protects it with barriers; when a goat uproots the tree, she is heartbroken. At the same time, the artifice of skilled craftsmen also fascinates her. Sitting in the women’s balcony in synagogue, Fayge looks down at the elaborately carved bimah where the Torah is read. Her older sister, Esther, is praying, but she is not: “She was looking, just looking…At the bimah, its wooden railing and canopy carved with pears and apples and curling leaves. Fayge wished that she could go down and curve her hands around a pear.” Fayge responds so deeply to the natural forms embedded in the wood that she loses any sense of personal boundary between herself and the ritual object. Her version of piety is as legitimate as the more formalized prayers of her sister.

Throughout history, women’s artworks have frequently been given lower-status as form of craft. Whether needlework, pottery, or jewelry — for personal or religious use — they have required the same level of expertise as the painting or sculpture more typically produced by men. Fayge’s mother, Gittel, herself a gifted craftswoman, intuits that her daughter needs an outlet for her artistic abilities: “What Fayge needs is to make something beautiful with those hands of hers.” She is as supportive as Ella’s mother, but her understanding of Fayge’s needs is deeper. While Ella’s mother views her involvement in the Shavuot play as a helpful distraction, Fayge’s mother recognizes that the creative process is an essential part of her daughter’s psyche. Given the family’s poverty, she can only provide materials for Fayge’s work by dismantling one of her most precious possessions, a basket covered in elaborate beadwork. In Ten and a Kid, Weilerstein portrays the chain of tradition between mother and daughter with as much dignity as the transmission of Torah study between father and son.

While Ella’s mother views her involvement in the Shavuot play as a helpful distraction, Fayge’s mother recognizes that the creative process is an essential part of her daughter’s psyche.

Her father had originally been dismissive of Fayge’s extreme sorrow over the loss of her tree, and the lack of common sense, which it implied. But he is convinced by his wife’s proposed solution and he offers to help Fayge to create a mizrach, the wall hanging indicating the eastern direction for prayer towards Jerusalem. Like Ella’s play, Fayge’s work will have religious and communal value, but in a more focused form. Ella’s range of performative proficiencies allowed her both to express herself and to enjoy the authority of coordinating the work of others. Fayge’s mizrachis exquisite on a smaller scale, a feminine version of the massive bimah, but somehow more powerful in its impact: “Around the border ran pears and apples with stems and curving leaves like the carved ones in the synagogue, only these glowed red and green and yellow.” Her father teaches her the Hebrew letters so that she may embroider the biblical phrase referring to the Torah as a “tree of life.”

Although Fayge’s masterpiece was designed for herself and her family, its unmatched quality draws the admiration of the whole town. Villagers stop by during Shavuot just to see it, standing “…in awe before the mizrach, admiring the glowing border, the perfect tree, spelling out the sacred letters.” Her work of art has become, in its own way, as instrumental to ritual observance as the synagogue’s bimah, her neighbors actively pronouncing her embroidered Hebrew letters a testimony to its importance. At the same time, everyone recognizes in Fayge’s gifts the legacy of her mother, many commenting that “The child has your hands, Gittel.” On Shavuot, when Jews commemorate God’s gift of the Torah to the people of Israel through His prophet, Moses, Fayge’s mizrachbrings women into the picture. Moses held up the stone tablets engraved with God’s law, while Fayge’s beaded letters make them tangible in her community.

The festival of Shavuot is multidimensional; children’s authors have often highlighted the centrality of Torah or the holiday’s historical origins in an agricultural society. Sydney Taylor and Sadie Rose Weilerstein, both concerned with the distinctive role of women in Jewish life, chose to examine those roles through the lens of artistic creativity in their Shavuot stories. On Shavuot, elements of the natural world and the fruits of artistic labor are both used to reflect the splendor of creation and the gift of the Torah. Ella’s untiring enthusiasm and relentless multitasking bring the story of Ruth and Naomi to a grateful audience, even as she affirms the value of her own identity as a performer and director. Fayge, a quiet young woman who outwardly conforms to societal expectations, is compelled to create works of lasting beauty. When given the opportunity, through her mother’s love and sacrifice, her work becomes a link in the chain of Jewish tradition; her mizrach is declared “a wonder, a marvel.” The wonder and marvel of women’s creativity, on a public stage or in the private canvas of home, are essential components of Shavuot celebration in these memorable books.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.